This is the prepared transcript of ‘Knowledge is power: an introduction to critical librarianship’, a talk I was invited to give at a professional development day for the NSW branch of the Australian and New Zealand Theological Library Association (ANZTLA). It was my first time delivering a virtual talk, which I found a lot less stressful than doing a regular talk because there’s no roomful of people creating a tense atmosphere. The Q&A was great and overall it was a really nice experience.

You will note that this is a very gentle talk. I was acutely aware that for a lot of attendees I represented their first experience of critlib theory and practice; a search of the literature for ‘critical librarianship’ and ‘theological libraries’ brought up precisely zero results, which strongly suggests to me that critlib isn’t (yet) a thing in this sector. I wrote this talk for a very particular audience. I tried to meet them where they are by using rather less fiery rhetoric than I’m known for, in an effort to ameliorate, rather than alienate. It’s broadly based on the article ‘Recognising critical librarianship’, which I wrote for inCite in January. I hope I could help kickstart some new conversations for theological librarians.

Thank you all for having me. It’s an honour to be invited to speak today. I’d like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands we’re meeting on, and in particular the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, custodians of the land I live and work on, which we now know as Canberra. I pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging, and extend that respect to all First Nations people who have joined us today.

My name is Alissa McCulloch and I believe that knowledge is power. The knowledge held by libraries, and distributed through the work of librarians like yourselves, can empower our users to do incredible things.

But knowledge, much like power, is not evenly distributed. Librarianship is steeped in tradition, but those traditions aren’t all worth keeping. The structure of librarianship can work to exclude, marginalise and harm people even before they’ve walked in the door. We like to think of libraries as spaces where everyone is welcome. But not everyone is made welcome in a library. What can we do about that?

We can start by exploring something called critical librarianship. You might also hear this referred to as #critlib. Applying a different ethical lens to the work we do every day. Doing things differently, in order to do them better.

Before I go on, I do need to emphasise that this talk represents solely my own opinions. These views are all mine and definitely not my employer’s! (But I think they’re pretty good views, so you know what, maybe they should be.)

The term ‘critical librarianship’ has come to describe two related but distinct approaches to library work. The first is the idea of ‘bringing social justice to library work’, or, How might libraries advance social justice issues, or achieve social justice goals? How can we make librarianship fairer, more accessible, and more equal to all our users?

The second is ‘bringing critical theory to library work’, an approach that “places librarianship within a critical theorist framework that is epistemological, self-reflective, and activist in nature”. It involves examining the ways that libraries support, and are in turn supported by, systems of oppression and injustice. It emboldens library workers to recognise and challenge those systems and reposition our professional work. And in turn it empowers our users, who can see the library reflecting the kind of society we all want to live in.

Throughout this talk I’ll use the words ‘librarian’ and ‘library worker’ interchangeably: critical librarianship applies to, and can be practised by, everyone who works in libraries.

In other words: it’s one thing to advocate for social justice in libraries, but it’s quite another to think about where and why is there social injustice in libraries in the first place.

Overdue fines, for instance. We’ve been fining people forever as an incentive to get them to return their books on time. We kept doing it because we thought it was effective, but it turns out the evidence for this is ambivalent at best. More importantly, in many cases fines can actively deter people from wanting to use the library, particularly low-income people who might already have racked up a heap of fines they can’t repay, or are scared of doing so (or their children doing so by accident). The kinds of people who can least afford to pay library fines are often the kinds of people the library most wants to attract—people who may also have lower literacy levels, who have small children, who are socio-economically disadvantaged, and (in academic libraries at least) people who might be first-in-family to attend university, or who might otherwise be struggling academically. Library fines are a social justice issue. It’s great that many public libraries have gotten rid of library fines, but I’m not so sure that many academic and research libraries have followed in their stead.

Much as we might like to sometimes, as librarians we can’t fix everything. We can’t solve these kinds of systemic injustices out there in the world. We can’t address the factors that contribute to library users being unable to pay their library fines. But we can do something about how those injustices manifest in the library. We can counteract that here, in this space that we maintain, in this time that we have. (We can do that by getting rid of library fines in the first place.)

Let’s come now to some key tenets of critical librarianship, which include:

- Bringing progressive values to professional practice—using libraries and library work to build a more equal and just society, and to actively address systemic harms as they manifest in the library (so things like systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, colonialism, capitalism, and so on).

- Part of this means actively questioning existing library structures, standards and workflows, and doing so through a particular ethical lens. Not just going ‘why do we do that thing’ or ‘how can we do this better’, which should be a normal part of good library practice, but ‘who does this harm’ or ‘whose interests are best served by us doing this thing’?

- Being a librarian doesn’t automatically make us better or more virtuous people. It just means we get paid to help people find stuff. It’s not a calling. It’s not the priesthood. It’s just a job. (But it’s a job worth doing well, and in some respects worth doing differently)

- There is no such thing as library neutrality—libraries are not, and cannot be, neutral. The core business of librarianship involves making a lot of moral and ethical decisions, such as ‘do we buy this book’ or ‘do we let this group use a meeting room’ or ‘do we pay this vendor this amount of money’. Those decisions are made in line with a given set of values. Not making a decision is a value choice. Trying to present ‘both sides’ of a given issue is also a value choice. I might disagree with a lot of traditional library values, but they are not the bastions of righteous neutrality they claim to be. Critlib values are a bit more upfront about this fact.

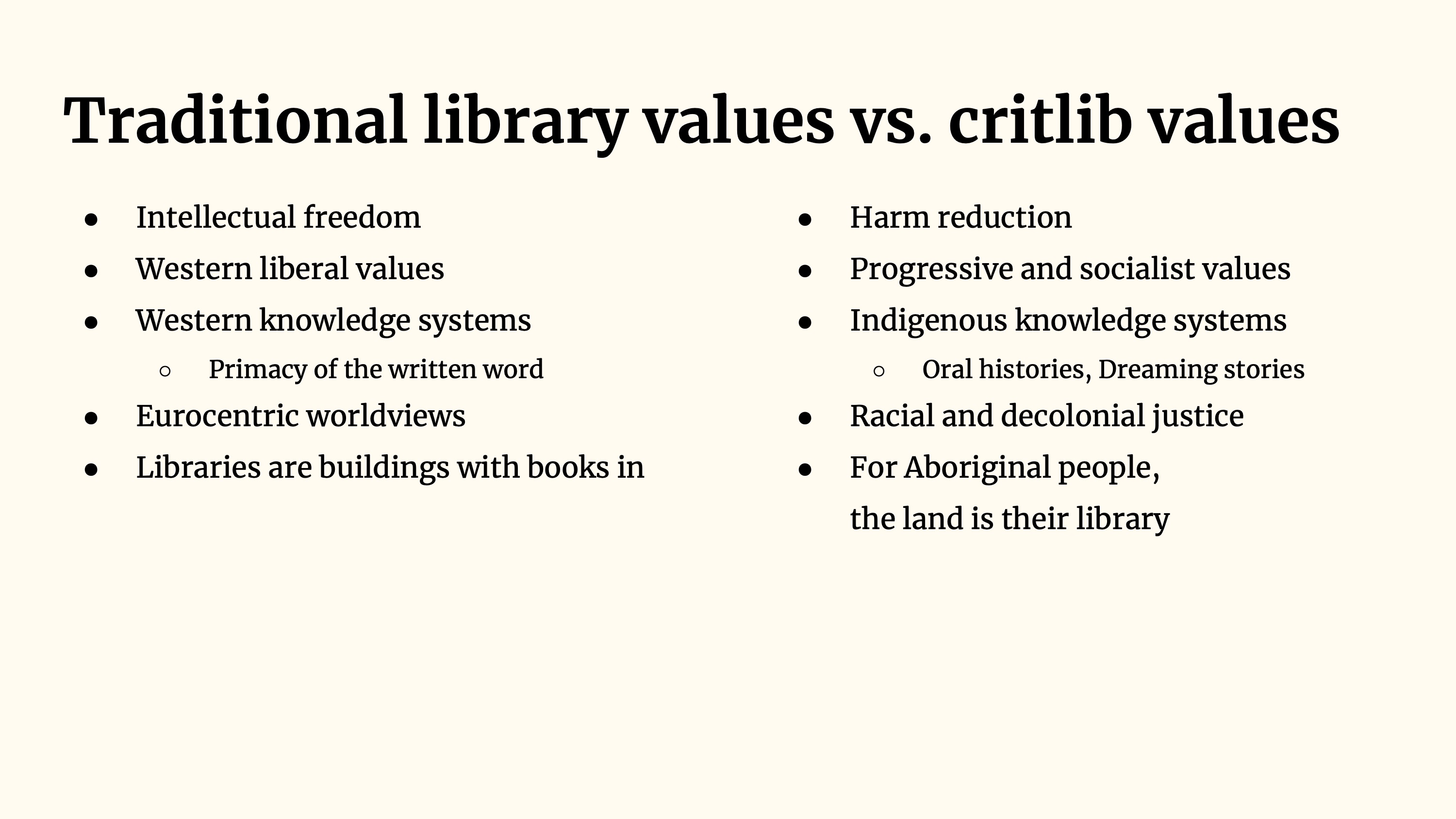

Traditional library values, like the ones you and I were taught in library school, place a high premium on things like intellectual freedom and Western liberalism. We say we’re not just about books anymore, but libraries are a key part of a book-based knowledge system. For the most part, the knowledge we store and deliver, and the knowledge we tend to trust, is stuff that’s been written down, and a traditional library is a building where that written-down knowledge is kept and safeguarded.

Critical library values, on the other hand, focus on things like harm reduction (which I’ll come back to a bit later) and progressive, socialist values (which you might think of as being a bit ‘left-wing’ but I don’t think the left wing–right wing dichotomy is terribly useful these days). Critical librarianship recognises the validity and deep importance of Indigenous and other non-Western knowledge systems, that oral histories and Dreaming stories are valid sources of truth and knowledge, just as much as books. I’ll never forget Jacinta Koolmatrie, an Adnyamathanha and Ngarrindjeri woman, teaching her audience at the New Librarians’ Symposium last year that for Aboriginal people, the land is their library, that knowledge and wisdom inheres in the landscape, and it deserves our care and protection in the same way libraries do. The recent loss of Djab Wurrung sacred Directions trees east of Ararat in Victoria is just as great a cultural loss as the destruction of a library.

Sometimes people can misinterpret the ‘critical’ part of ‘critical librarianship’, and think that we’re all just about having a big whinge, or that it’s a professional excuse to be rude or disparaging about library work. And I just want to make clear that that’s not what we’re about.

It’s about making the profession better by recognising harmful practices and oppressive structures, dismantling those things and building better ones in their stead. It’s about leaving the profession in a better state than when we found it. We critique because we care. I have a lot of feelings about librarianship! And I care very deeply about what I do. If people didn’t care so deeply about the profession, we wouldn’t be spending all this energy on making all this noise and doing all this work.

Over the next few slides I’ll take you through some of the ways critical librarianship intersects with my work. I’ve spent my career largely in back-of-house roles, what you might traditionally call ‘technical services’, so things like collection development, cataloguing, and my newest role in library systems. Naturally critlib happens front-of-house too! And there is quite a lot of literature on critical reference and critical information literacy. But I’ll leave that analysis to others.

Critlib comes up most often, and is probably most immediately visible, in the realm of collection development and acquisitions—looking at the materials your library collects and provides. Think for a moment about who your library collects. Are the bulk of your materials written or created by old white guys? Now I get that in a theological library, the answer is likely to be yes. Think about how many of your materials are written or created by women? People of colour? Indigenous people? Queer people? Disabled people? Combinations thereof? It’s not just about a variety of theoretical or academic views, and it’s also not about collecting other voices for the sake of it. It’s about making different perspectives and life experiences visible in your library’s collection. It sends a message that the library doesn’t just belong to old white guys—that it belongs to all whose views and life experiences are included here.

Everyone deserves to see themselves reflected in a library space, but it is also critical that everyone doesn’t only see themselves reflected in that space, that our diversity reflects that of the communities we serve. (I’m reminded of a quote from Nikki Andersen, a library worker I deeply respect, who said last year “When someone walks into a library and can’t find a book that represents them or their life, we have failed them. Likewise, if someone walks into a library and only see books that represent their life, we have also failed them.”

It’s one thing to have materials representing the diversity of human experience, but it also matters what those materials say. It’s no good having materials about Indigenous issues that were all written by white people thirty years ago, or things about homosexuality written by straight people who deny our humanity. The adage of ‘nothing about us without us’ holds especially true.

Theological libraries are naturally quite specialised and so you’re unlikely to be collecting material that doesn’t fit your collection development policy. A book on landscape architecture or whale-watching might be very interesting, but not relevant to the work of your institution. If you choose not to purchase it, it’s not censorship. It’s a curatorial decision. Whale-watching’s not in the CDP.

Similarly, a public library (in my view) should not feel obliged to purchase a copy of a text by a far-right provocateur if they feel that doing so would not be in their community’s best interests, or would cause demonstrable harm. They’re not denying their community the ability to read the book—they’re simply choosing not to stock it. In this instance, they’re applying the concept of harm minimisation to library collection development, prioritising community wellbeing and cohesion over the intellectual freedom of an individual. This situation might be different in an academic library, where they may feel the research value of such a book outweighs the potential harm it could cause. Potentially this decision could be contextualised in the book’s catalogue record, which I’ll come to in a second. But these are individual curatorial decisions for each library. They are made in accordance with that library’s values, and they are certainly not neutral.

Now, you might hear this and go ‘well how is that any different to, say, a parent demanding a school or public library remove a picture book about gay parents, claiming it is harming their child’? How is that different to the library I’ve just described deciding to remove, or not purchase, a hateful rant by a far-right author? Besides, shouldn’t we be trying to present ‘both sides’ of an issue, for balance? My answer to this is: by retaining the book about gay parents we are affirming their humanity and place in society; we recognise that they are not seeking to harm anyone just by existing; and we are validating their story. By not purchasing the far-right book we are doing the opposite; we are choosing not to do those things. We’re not censoring the book—we’re just not validating it. False balance is harmful and does our users a deep disservice. That’s a values decision, and if it were up to me it’s one I would stand by.

Or, put slightly differently… ‘something to offend everyone’ is not a collection development policy.

Until last week I was a full-time cataloguer, so critical cataloguing and metadata is kind of my speciality. I’m endlessly fascinated by how libraries describe and arrange their collections, whether it be on a shelf or on a screen.

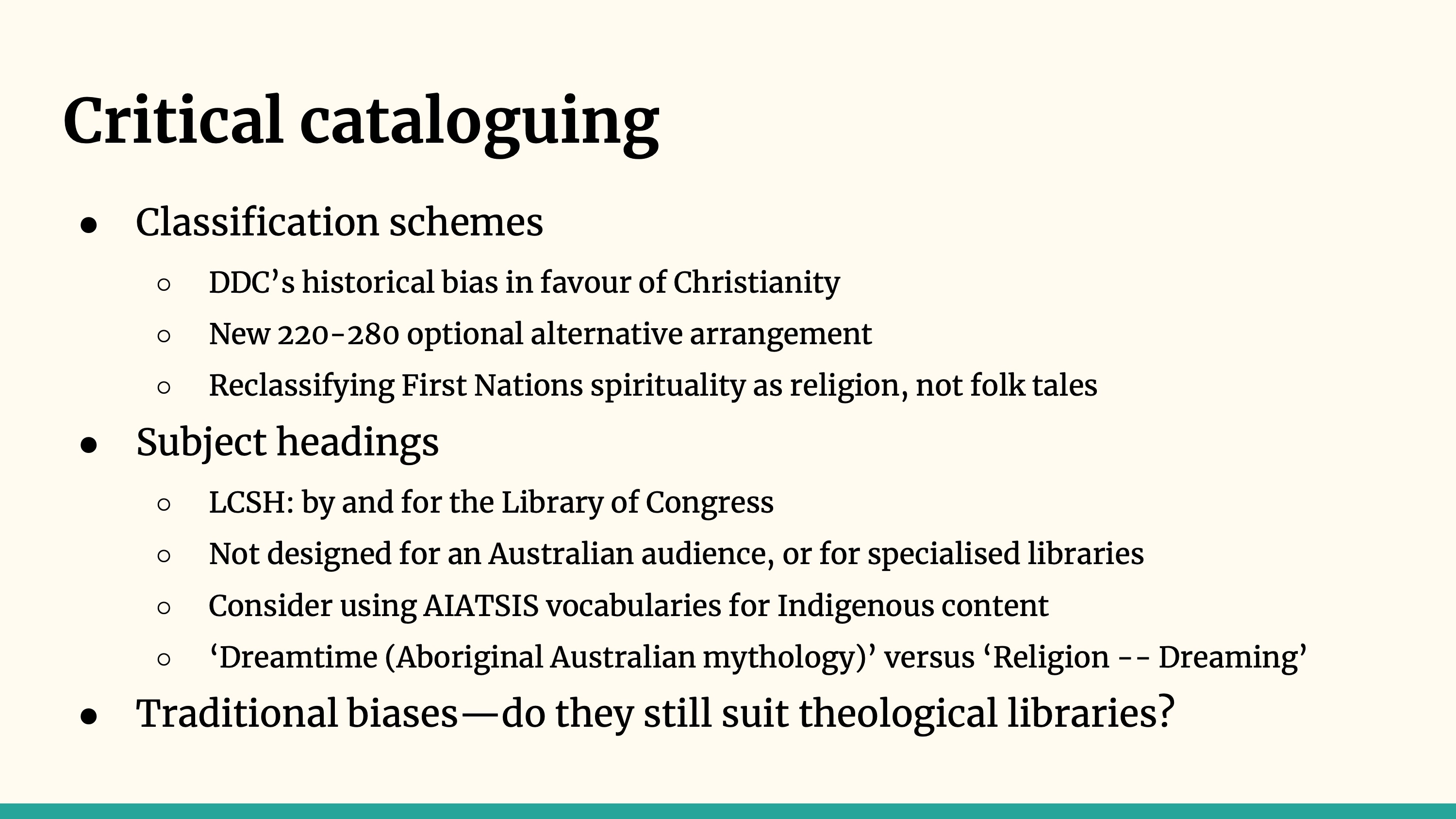

As many of you will likely be aware, the religion section of the Dewey Decimal Classification has traditionally allocated quite a lot of space to Christianity and comparatively little space to other religions. You may be interested to know that the editors recently released an optional alternative arrangement for the 200s, which attempts to address some of these structural biases and make the distribution of religions a little more equitable.

Dewey has also historically copped a lot of flak for classifying works on Indigenous and First Nations spirituality, including Dreaming and creation stories, as ‘folk tales’ in 398.2 and not in the religion section. Dewey itself has instructed since about the mid-90s that such works should be considered religious, and classified as such. The fact this grievance has persisted for so long suggests a pattern of unconscious bias on the part of the cataloguer—they might not have recognised Indigenous spirituality as a ‘religion’ in the Western sense, and so didn’t classify this stuff there. But this lack of recognition is very obvious to Indigenous people, and it matters.

By the way, has anyone ever thought about how weird it is that we use Library of Congress Subject Headings? Like, we’re not the Library of Congress, we’re not Americans, we’re not government librarians, but we use their vocabulary and we inherit their biases. We do this mostly out of convenience and because it’s more efficient to use somebody else’s record, but I often wonder how useful or meaningful this language is in Australian libraries. I’d love to see more widespread use of things like the AIATSIS vocabularies for Indigenous content, which are designed to reflect an Indigenous worldview, and specify—that is, give names to, and therefore surface in catalogue records—issues and concepts of importance to Indigenous Australians.

For example, consider the difference between these two headings for Indigenous Australian creation and origin stories. LCSH calls these ‘Dreamtime (Aboriginal Australian mythology)’, while AIATSIS uses the faceted term ‘Religion — Dreaming’. Now, neither of these terms is neutral, because nothing about librarianship is neutral, but while the LCSH term is pretty clearly from a Western perspective classifying these stories as mythology and not religion, the AIATSIS term does the opposite, in line with Indigenous conceptions of their lore, and recognising their right to describe their culture their way. Using these terms in a library catalogue sends a message that these are the terms the library prefers, and in so doing makes the library catalogue a more culturally safe place for Indigenous people. It’s about taking social justice principles of diversity and inclusion, applying critical theory to our controlled vocabularies, and ultimately making better choices in the service of our users. This is critical librarianship. And in my opinion, it’s also the least we can do.

While researching this talk I was really struck by how so many of these historical biases would have traditionally really suited theological libraries—lots of classification real estate for Christianity, detailed LCSH subdivisions for the heading ‘Jesus Christ’, and so on. But I don’t work in a theological library, and I don’t know if that still holds or not.

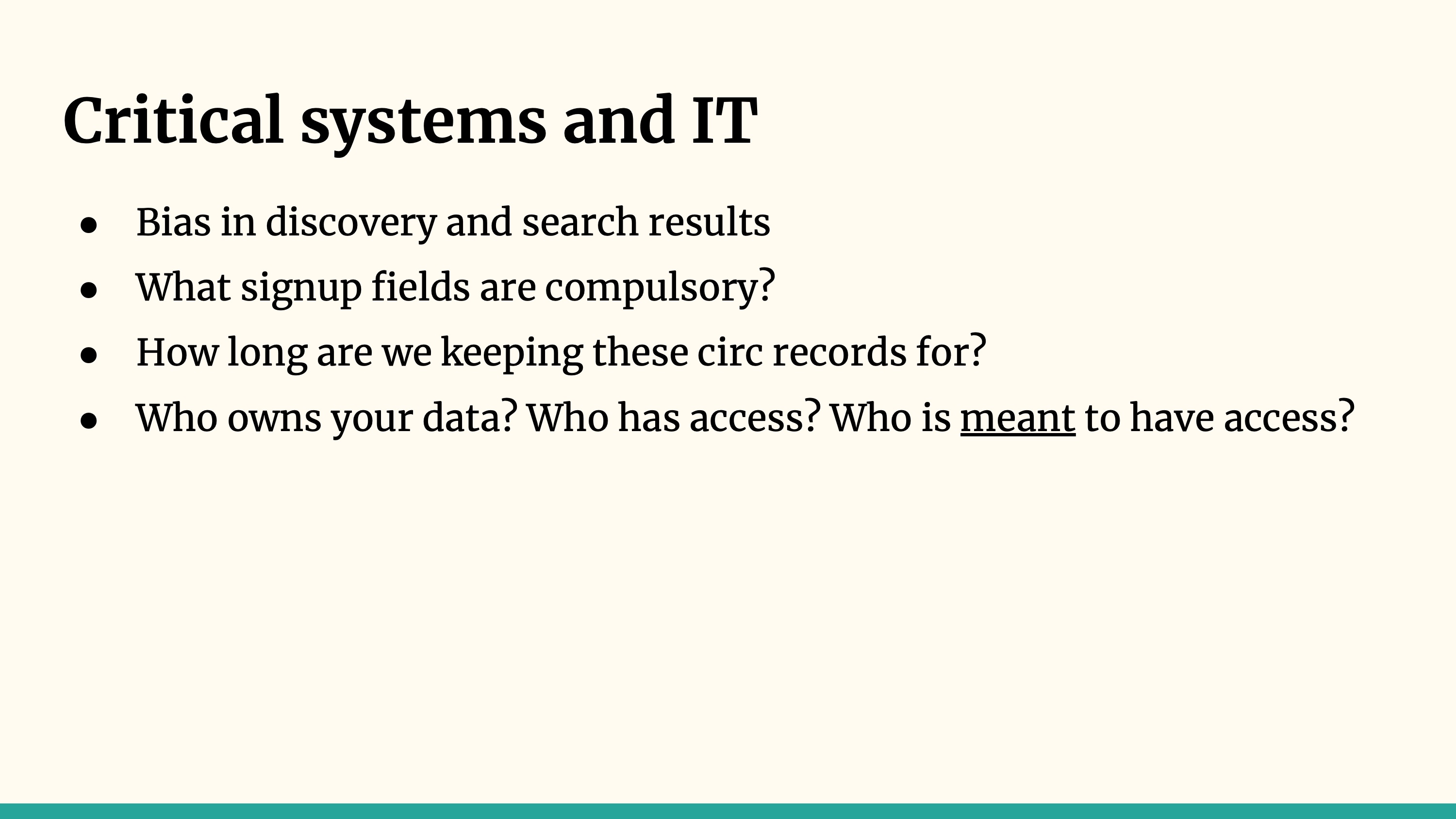

This week I’ve actually started a new job as a systems librarian, so I’m particularly interested in this facet of critical librarianship. We might not immediately think of systems as being particularly problematic, but systems reflect the biases and perspectives of the people who build them, and to a lesser extent those of people who buy them.

For example, most library catalogues and discovery systems will allow you to rank results based on ‘relevance’. How, exactly, does the system determine what is relevant? How much potential is there for bias in those search results, either because your metadata is incomplete, outdated or otherwise unhelpful; because your system autocompletes what other people search for, and people search for really racist and awful things; or because your system vendor also owns one of the publishers whose content it aggregates, and it suits them to bump that content that they own up the rankings a bit? This happens, believe it or not—there’s a whole book on this topic called ‘Masked by Trust: Bias in Library Discovery’ by Matthew Reidsma, which is excellent (and also sitting in a moving box behind me).

We could also consider the kinds of data that library systems ask for and keep about people. When you sign up new users to the library, which fields are compulsory? Do they have to specify their gender, for instance? Why does the library need to know this about somebody in order to loan them books? What kind of data are we keeping about the books people borrow, their circulation history? How long do we keep it for? Who has access to it? Would we have to give that data to the police if they asked, or had a warrant? (If we didn’t keep that data, we couldn’t then give it to the police, hey.) Is your system vendor quietly siphoning off that circulation data in the background to feed it to their book recommendation algorithm? Do we want them to do that? My local public library actually does this and I really wish they didn’t, to be honest, it makes me very uncomfortable, and frankly it makes me not want to go there.

We want our library systems to have the same kinds of values that we have as people. But more often than not libraries end up functioning in ways that suit our systems. To me, that seems a bit backward. I firmly believe that systems should work for people, not the other way around.

Just before the American presidential election, the Executive Board of the American Library Association released a statement in support of libraries, library workers and library values. They noted that: ‘Libraries are nonpartisan, but they are not indifferent.’

To me, this sentiment lies at the heart of critical librarianship. So much of this discourse gets tied up in misunderstandings over whether libraries are, or should be, political. You’ll notice I’ve avoided using the word ‘political’ in this talk for this reason, because people interpret the question of whether libraries should be political to mean ‘supporting one political party over another’ or ‘supporting the activities of government’, and that’s not what critlib means. Everything I’ve outlined today is a political act. Many of them are progressive acts. But they are not partisan acts. They are acts that are conscious of the power they wield, and consciously try to direct that power in support of building libraries that better reflect and support the communities they serve. These acts are steeped in an ethic of care. Libraries do not exist in a moral and political vacuum. We are part of society, too. And we as library workers can do our bit to help make our society better.

It has taken a very long time for organisations like ALA to come to this party. I have lost almost all hope that ALIA will ever show up, but we will welcome them when they do. There’s a lot of work ahead. Let’s get started.

Thank you 🙂