Wow, what a shit year.

It was intense and horrifying and miserable and lonely and exhausting. The world ended. And yet we’re still here.

I learned a lot this year. I learned that working from home is great, actually; that lockdown really isn’t that much different from my usual life, but it still sucks; that the sounds of forests are a better antidepressant than any medication; and that months after the most traumatic experience of my life it’s still so hard to say certain things out loud. I also learned that I often sound better than I feel. It still amazes me that I was able to write something as coherent as ‘The parting glass’ less than a week after leaving hospital, at the peak of the first wave, at the end of everything. I was desperate to be heard, to be known, to be cared for, to be safe. I still am. It’s a work in progress.

Among many other things I started a new job this year, thanks to my workplace’s pre-existing restructure. It’s kind of a systems librarian role, lots of data maintenance, gathering, querying, harmonisation. A new role in an old team, but I have been made so warmly welcome it’s like I’ve been there for years. I’m pleased that this work is being resourced (though I wish it weren’t at the expense of other areas). Quiet, routine, meaningful, honourable work, in the Maintainers tradition. The work that keeps everyone else working, though it’s hardly ‘essential’ in pandemic terms, and is 100% doable from home. I found myself drawing on the white paper ‘Information Maintenance as a Practice of Care’, embodying its values into my work.

I see my new role as a caretaker, a systems janitor, a data maintainer. My job is to nurture our data systems, help them grow, water them, prune them, compost them at an appropriate time. Our ILS is 17 years old and desperately needs replacing. We’ll take care of it as much as we can, while planning a new system that might flower for longer, and make better use of resources.

I love this job so much partly because I now get to work with some really excellent people, but also largely because this team are far better anchored in the bigger work of the library. Being a traditional cataloguer meant I had a very narrowly focused view of metadata. I dealt with records at the micro level, one item at a time, with little to no ability to see the bigger picture. It wasn’t that I couldn’t personally see it; rather, my job and team structure lacked that oversight. But now my role deals with metadata at the macro level, many thousands of records at once, where the system shapes our view. I find it deeply grounding as a metadata professional, seeing the ebb and flow of data, how it can help tell a greater story, how what we don’t record often says as much about an item, and about us, as what we do record. I’m hopeful we can make space for some work on identifying systemic biases in our metadata; our cataloguing policies mandate the use of AIATSIS headings and AUSTLANG codes for First Nations materials, but is that actually happening? How comprehensive is that data corpus?

I’m acutely mindful of not wanting to use these powers to dump on our put-upon cataloguers who already have loads of people telling them what to do and minimal agency over how they do it. Trust me, I used to be one of them. I don’t want to reinforce that cycle. I would much prefer to work with cataloguers and their supervisors to show them the big-picture insight that I didn’t have, to empower them to select the right vocabs for the right material, and to record what needs recording. In data, as in horticulture, many hands make light work.

I might have become a caretaker at work, but this year we were all also caretakers of each other. Taking care as well as giving care. It intrigues me that ‘caretaker’ and ‘caregiver’ mean broadly the same thing: the former is more detached, as if tending to a thing or an inanimate object, while the latter is closer, more familial: a responsible adult. To ‘take care’ means to look after oneself, while being a ‘caretaker’ means looking after something else. I am thankful to those who cared for me during my darkest hours. I have drawn great strength from the care of close friends, for whom my gratitude is everlasting. Without you I would not be here.

It’s safe to say my professional responsibilities took a back seat this year. I hope next year to get the ALIA ACORD comms up and running, complete some work for the VALA Committee, and sort out whatever else I said yes to. (Honestly I’ve completely forgotten.) I did give one talk this year, a presentation on critlib for the ANZTLA. I hope it can help grow some new conversations in the theological library sector.

In 2020 I somehow wrote 15 blog posts, including five for GLAM Blog Club. Usually I’d note my favourite post of the year, but honestly writing anything was so difficult that I’m nominating them all. I think ‘The martyr complex’ hit a nerve, though. I despair for library workers overseas, still having to open their doors to the public in manifestly unsafe conditions. Apparently CILIP CEO Nick Poole has been reading this blog, so if you see this, Mr Poole, you must call for the urgent closure of all public libraries in Tier 4. Nobody ever died from not having a book to read.

I’m saying this out loud because I need to, as much as I want to: next year I am absolutely doing less library professional busywork. It has to stop. I know I’ve said this before—my goal for 2020 was ‘to do less while doing better’ and look how that panned out—but I actually am gonna do it now. I need less of all this in my life. Less computers. More nature. Less doomscrolling. More reading. Less zooming. More walking. Less horror. More consciousness. Less overwhelm. More saying no to things. Please don’t take it to heart if you hear me say no a bit more next year. It’s not you, it’s me.

In part I can promise these good things to myself because I live in a city that currently has one covid case. One. A single one. Life is relatively normal here, barely anyone wears a mask (though I did get yelled at by an old man the other day for not keeping 1.5 metres away from him… on a bus). I have mental space for this stuff in a way the northern hemisphere does not. In some ways it feels like living in a postmodern remake of On the Beach, but as difficult as my life is right now, it could all have been so much worse.

The pandemic accelerated social changes I had already seen coming. I had long ago vowed to live a smaller life. I gave up flying almost three years ago for climate reasons, deciding instead to explore my own country, understand more deeply my own city and surroundings, while trying to detach myself from endless grim horrors abroad. I am powerless to help and can only absorb so much. I am needed here. I can do good here, now, in this place, in this time.

Logically I know my good fortune, but my brain persists in telling me otherwise. I was already very unwell at the start of this year; in many ways the coronavirus outbreak was the final straw. This time last year I was having a panic attack in a friend’s backyard. This time nine months ago I was being admitted to the psych ward. My illness was life-threatening. I did not expect to see Christmas.

There can’t be many people out there whose mental health at the end of this year is better than it was at the start. I have found great solace in the latter-day writings of Sarah Wilson, whose book First we make the beast beautiful: a new story about anxiety was the last book I bought in person before everything fell apart, and whose new release This one wild and precious life I look forward to bringing with me on a brighter path.

To the extent I have any goals for next year—other than continuing to not die—I hope to do more of the things I enjoy, rather than reading about them in books. Books have long been my way of making sense of the world; according to my mother I learned to read at the age of 2 1/2 and would happy babble away reading the newspaper (sometimes I even understood it, too). Books make sense in a way people never have. Books are solid, portable, dependable, usually upfront about things, and even if they’re not it can occasionally be fun to decode or divine their real meaning. Books generally have a point. People often have no point and are seldom upfront about things. It makes life deeply frustrating.

Another book I acquired just before lockdown was Lucy Jones’ Losing Eden: how our minds need the wild. It’s still in a moving box, stored away due to lack of shelf space. But I’m sure the author would be just as happy if people took her message to heart and ventured outside a bit more anyway. I couldn’t face it during April, when going outside was dumb and illegal, but perhaps this coming year, in my suspiciously covid-free paradise, would be a good time to revisit.

My goal is not to lessen my reading. I didn’t finish a single book this year. And that’s okay because I kinda had bigger things to deal with. But instead of reading about the delights of nature, I think I would prefer to experience them myself. Like many in the book professions, I have a terrible habit of buying really interesting-looking books, placing them on a shelf, and then acting as if I have read them and absorbed their wisdom by osmosis. I would like to read more, but I would also like to go outside more, walk more, take flower photos more, cycle more, do the things instead of reading about them. I hope to take care of myself. I hope to take care of others. I hope others might still take care of me.

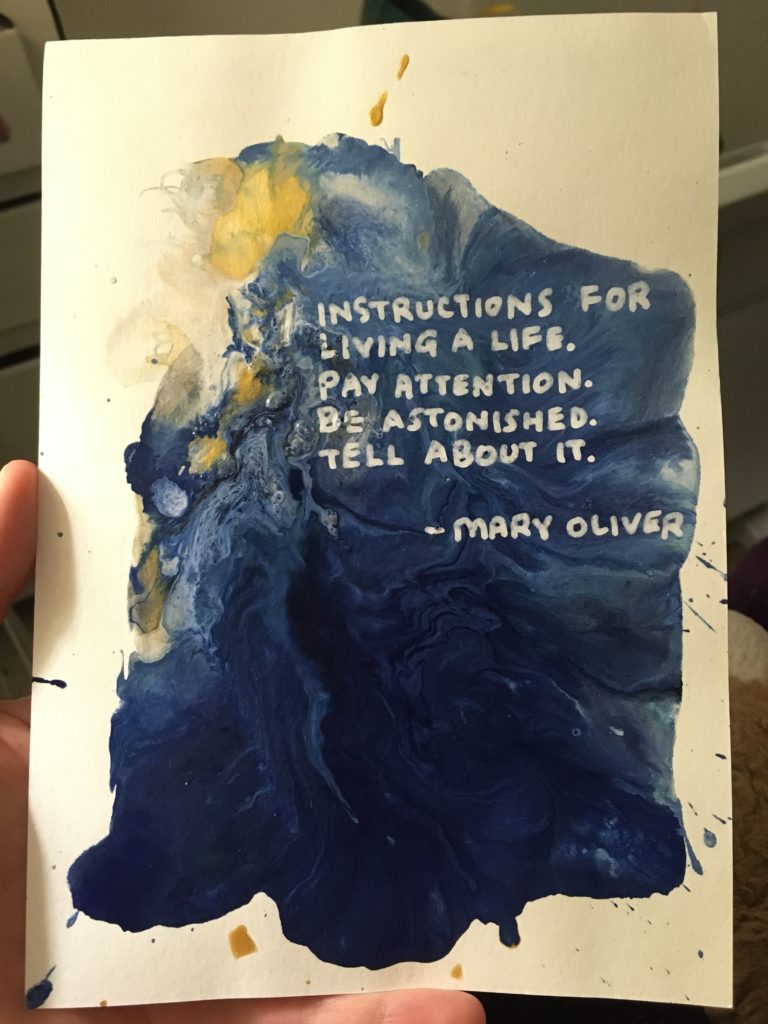

Or, in other words, as painted by a dear friend: