Yeah, I know the deadline for submissions to the ALIA Future of LIS Education discussion paper was two days ago. I’ve been all of the usual things: busy, stressed, unwell, preparing to move house and reapplying for my own job in the same week. Small fry, really. I also coordinated a submission in my capacity as Information Officer for ACORD, the ALIA Community on Resource Description, which focused on matters of interest to the Australian cataloguing and metadata sector. But a few bigger thoughts kept gnawing at me, and I decided to write them up anyway now that I have a sliver of brainspace, for general consumption as well as for ALIA’s attention. These views are, as always, solely my own.

I’ll admit to not having been privy to a lot of the professional conversation on this topic, but much of what I did hear focused on the issue of library workers having library qualifications (or not). Most job ads I see these days ask for an ALIA-recognised qualification or equivalent experience. Employers are already recognising the many paths people take to a library career, but they’re also recognising that eligibility for Associate membership doesn’t really mean very much. Of the four libraries I’ve worked in, only one specifically said I needed to have a library degree. I didn’t have a library degree. I got the job anyway. 🤷🏻♀️

I think employers are also frustrated by library school graduates being unable to meet the immediate needs of contemporary libraries. The skills employers need are not the skills educators are teaching; I graduated two years ago and recall being very surprised by the chasm between what I was taught and what I was seeing with my own eyes at work.1 Our sector benefits hugely from the diverse educational backgrounds of its workers, be they graduates of university, TAFE, or the school of hard knocks.

This issue cuts both ways, however: I’ve written before on the ‘price of entry’ to the LIS field, where librarianship remains on the Government’s skills shortage list despite an apparent surplus of graduates. Employers say they want ‘job-ready’ grads, but what I suspect they really want is to not have to train people in the specialities of a particular role, especially as entry-level positions continue to disappear. At the same time, though, a comprehensive LIS education has a duty to balance employable skills with a solid theoretical grounding—in other words, to learn what to do, as well as why to do it. It can’t be solely about ‘what employers want’, otherwise our moribund industry would truly never change.

This comment on page 10 of the discussion paper was… uh, quite something:

During our discussions, there were different perspectives on the division between Librarians and Library Technicians. Some felt this was a necessary distinction; that Librarians should be conceptual thinkers and Library Technicians should have the technical expertise, for example with resource description and technology devices.

This distinction is hogwash. Our sector desperately needs people with both these qualities, who are conceptual thinkers with technical expertise. I am a professional cataloguer with a master’s degree. For better or worse, I never went to TAFE. I learned to catalogue the long way. I firmly believe it has made me a better cataloguer, more able to question and deconstruct our hallowed bibliographic standards, to call for change and to make it happen. To state that resource description does not require conceptual thinking is offensive to the cataloguing and metadata community. The idea that information technology does not require it either is even more ludicrous.

I suspect this view is based on a public library’s operating model, where library techs help senior citizens with their iPads while librarians are the ones in charge. The job title of ‘library technician’ has strayed so far from its original meaning that nowadays it seems to mean ‘TAFE-qualified lower-paid library worker’ irrespective of job function, and sits below ‘librarian’ in a workplace’s hierarchy. The word ‘technical’ has a long and twisted meaning in LIS (and yes, I’ve written about that too), but we can safely say that most library IT work is done by people earning far more than a library technician’s wage. It’s a confusing term both inside and outside the industry, and it needs to go. So too does the hierarchy.

Anyway, back to qualifications. The discussion I’ve been seeing is predicated on the idea that the only way to be an accredited library professional (that is, a ‘librarian’ and not a ‘library technician’) is by getting an accredited library degree. Currently that’s the case in Australia. But what if I told you… there is another way?

My primary recommendation for the future of LIS education in Australia is this: I would like ALIA to consider adopting the LIANZA Registration model of professional accreditation, focussing on accrediting the individual, as well as the institution.

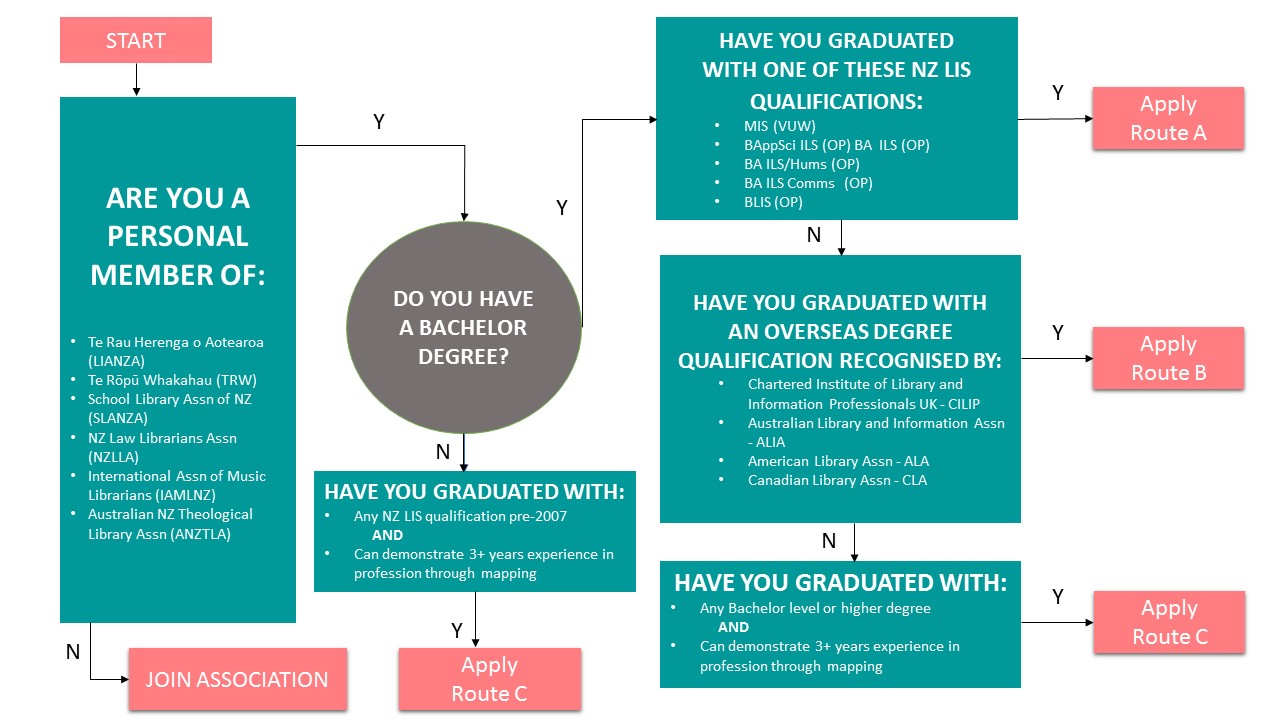

Prospective library professionals in Aotearoa New Zealand have three options. They can:

A) Complete a recognised New Zealand library and information qualification;

B) Complete a recognised overseas library and information qualification; or

C) ‘Demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the Body of Knowledge’, along with 3 years’ professional experience, plus either a pre-2007 NZ LIS qualification, or a bachelor’s degree in any discipline.

They must also be an individual member of a recognised library association in New Zealand (LIANZA recognises six, including itself), and pay an annual fee to LIANZA.

I’m fascinated by the potential of option C). A prospective applicant need never have set foot in a LIS classroom, but if they have already demonstrated their intellectual aptitude at the undergraduate level, gained substantial experience in library work, and can map their knowledge against recognised competencies, then they can gain professional recognition equal to that bestowed upon library school graduates. In no way does it devalue the hard work of those graduates; it acknowledges that there are many paths to the same goal, and respects professional learning in all its forms. It recognises that librarianship is a profession by mandating a professional-level (i.e. university) qualification.2 Crucially, it also better reflects what’s actually happening on the ground.

LIANZA’s eleven ‘Body of Knowledge’ competencies outline the key skills and responsibilities of contemporary library and information workers, and cover the same kinds of material that would be taught in library school. Of particular importance is BoK 11, ‘Awareness of indigenous (Māori) knowledge paradigms’. Every accredited library worker in New Zealand must demonstrate this competency. This is not the case in Australia, where LIS professionals can—and do—go their entire careers without knowing a single damn thing about First Nations knowledge systems. It’s one of many reasons why our profession is white as hell. It makes the task of developing and maintaining culturally safe libraries that much harder, for First Nations library users and workers alike. It also perpetuates a knowledge monoculture, which is actually really boring. I wish more of us could recognise First Nations knowledge of the land as a kind of library.

Like ALIA membership, LIANZA Registration is optional. The closest ALIA currently gets to option C) is Allied Field membership, which is very deliberately not the same as ALIA Associate membership, and renders the former ineligible for jobs that require the latter. Presumably ALIA is trying to protect the existing higher education pathway. But that pathway is already collapsing: two days before the close of submissions to this paper (so, four days ago), word spread of RMIT’s intention to close its library school and teach out its courses. The status of information studies at Monash University hangs by a thread. Both universities have been hard hit by the aftereffects of the coronavirus pandemic, including the collapse of international student income and the ineligibility of public higher education institutions for jobkeeper. And that’s even after the massive fee hikes to HECS-eligible humanities and social sciences courses, which includes librarianship (but not teacher librarianship, which is classed as education).

Without RMIT, there would remain just four universities offering library degrees in Australia: Curtin, Monash, UniSA, and Charles Sturt. Curtin has already cut its undergraduate LIS courses. Monash could be on the way out altogether. UniSA is a bit of a dark horse. And Charles Sturt, while by far the largest library school in Australia, is not immune from cost and enrolment pressures.

The discussion paper notes wryly on page 12:

ALIA’s priority has been, and continues to be, supporting our accredited courses. However, it would be negligent for the sector not to consider a ‘Plan B’ in the event of the university system failing us.

Through little fault of its own, the university system is clearly already failing the Australian library and information sector. The time for Plan B is now. Automatically enrolling ALIA members into the PD Scheme does not go far enough. It’s time for ALIA to move to an accreditation model that better recognises, and does justice to, the diversity of educational and life experience among Australian library professionals. It would mean a bit more work for ALIA, yes, but I’d like to think it would make ALIA professional membership a more attractive and meaningful option. Let’s make ALIA Associate status more widely available to graduate library workers across disciplines, by providing an equal pathway to professional recognition that won’t break the bank.

- It’s worth mentioning that I had zero library experience when I began my MIS—which I hear is not uncommon—so my first impression of library work was in the (virtual) classroom. ↩

- This concern was publicly raised by Charles Sturt University’s School of Information Studies in its response to the discussion paper. ↩