At Alex Bayley’s invitation, I compiled a short list of books that collectively explain, or at least excuse, the inside of my head. Books that say more about me than my resume. Well, my resume suggests I’m a chronic library overachiever, so here are some books that are not about libraries. I think it ended up mostly being an excuse to tell embarrassing bookish anecdotes about my childhood.

This list does not, and necessarily cannot, reflect the many periods of my life where I was so unwell I stopped being able to read books at all. Instead being portals of wonder, books became piles of words I couldn’t process. For someone who learned to read precociously early this has had a profound effect on my reading habits. I’ve become a slower and choosier reader. Words take longer to sink in, now.

At the moment, the inside of my head is mostly white noise and static. This list represents what my brain normally looks like when it’s not trying to eat itself.

These also aren’t in any particular order, except I read the ‘earlier’ books, uh, earlier.

Earlier

His Dark Materials / Philip Pullman

A primary school classmate who shared my name but spelt it wrong insisted our teacher read Northern Lights to us as part of class storytime. I was captivated. Mum bought me the trilogy for Christmas that year. I thought it was brilliant, full of suspense and intrigue and characters that felt real, and also not real. Looking back I think I read the series a touch too early; virtually all the adult references and a lot of the deeper mythology went way over my head. I haven’t seen the TV adaptation. I think I’d prefer to keep my imagination intact.

Antimatter: the ultimate mirror / Gordon Fraser

This was my favourite book when I was ten years old. I’m not even joking. I made a habit of going to the same shelf in the local public library and continually borrowing the same book on particle physics because I found it all so fascinating. I recall liking this book because it had less maths and more science, which I guess means the prose was engaging enough that I could skip the more mathsy parts.

One day someone else borrowed the book and returned it to a different library. I was devastated. I didn’t know how holds worked. I think I waited for the book to come back of its own accord. I’m not sure it ever did. They’ve weeded it now.

A young person’s guide to philosophy / Jeremy Weate

When I was nine I won a prize in the MS Readathon for reading the most books in the whole of the ACT. They abolished the prize the year after I won it, possibly because they could tell I rorted the system by reading all of my younger brother’s thoroughly boring Thomas the Tank Engine readers. (Mum foolishly agreed to pay me by the book.) The prize was a $20 gift voucher at Angus & Robertson.

Normal children would probably have bought a novel or two. I bought an illustrated philosophy book instead, and got the bookshop staff to photocopy the prize gift voucher and paste it in the front. I liked reading about Hypatia. She was illustrated wearing a purple toga and riding a chariot. I thought that was the coolest thing I’d ever seen. Descartes sitting in the stove was markedly less appealing.

Later

Sand Talk / Tyson Yunkaporta

I haven’t finished reading this yet but I also haven’t been able to shut up about it. It’s incredible. The sharp and clear-eyed prose belies a geo-socio-temporal intricacy that whitefella here can only begin to grasp, of the deep patterns that inform Indigenous knowledge, and how recognising, appreciating and ultimately following those knowledge paradigms might help us all live better on this land.

Nothing I say here will do this book justice. It’s one of the best things I’ve started reading in years.

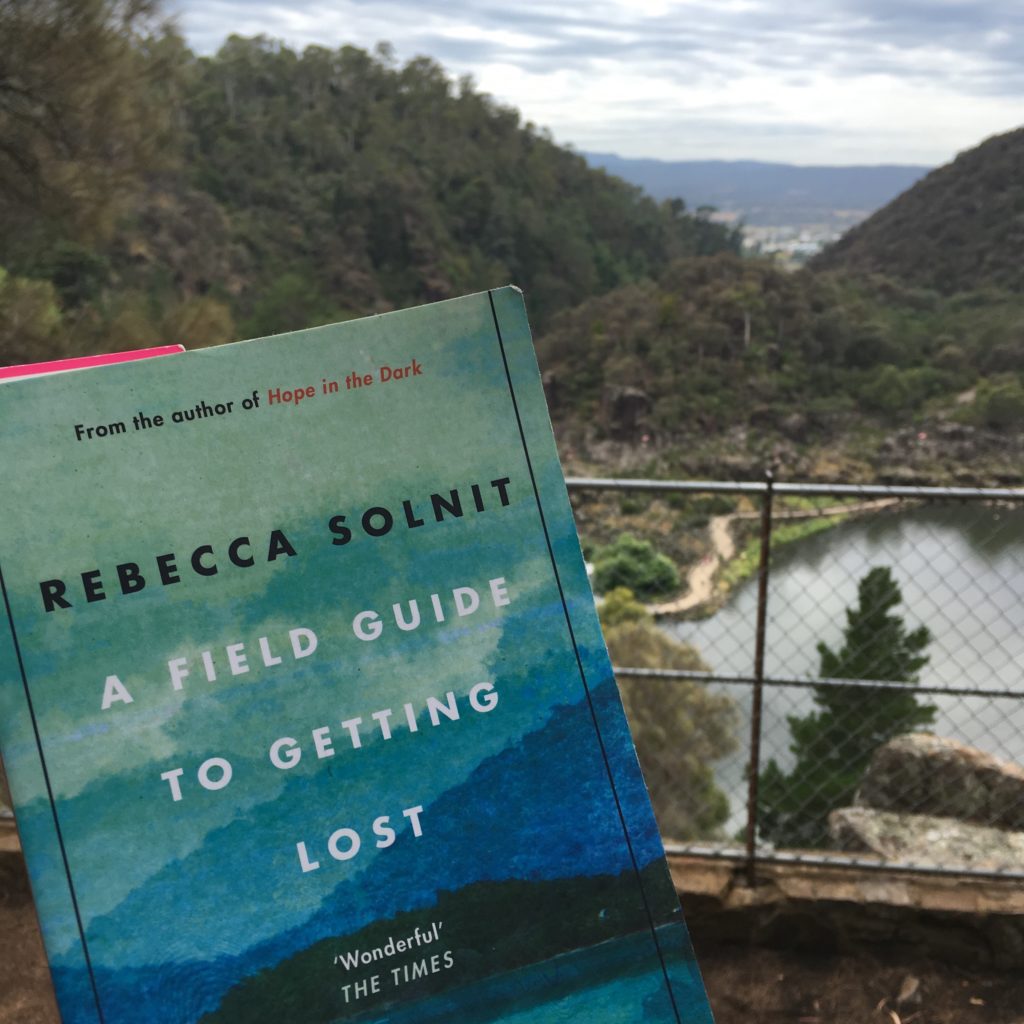

Hope in the Dark / Rebecca Solnit

I now read this book medicinally. Take a chapter at bedtime, when the news is grim. It won’t fix the news, and it might not fix you, but it will give you some perspective back. I experience time differently when I’m unwell; my perspective narrows, time grows shorter and greyer, I forget the past and can’t see the future. Sometimes Hope in the Dark is a distraction, and sometimes that’s all I need, but other times it helps me contextualise things, reminds me that in many ways we have been here before. Perhaps we all ‘oppose the ravaging of the earth so that poetry too would survive in the world’.

I notice Hugh also included this book in his bibliography. I’ve still got his copy. I’ll return it soon, I promise. Just as soon as hope comes back.

The Anthrobscene / Jussi Parikka

Once upon a time we were all told that doing things electronically was good for the planet because it saved trees. We now know that’s not true, right? Everything that goes into a computer is mined from the ground, and this book combines media studies and earth science in exploring the effects of modern computing on the planet and the materiality of our digital habitat.

To be honest, I didn’t understand most of this book the first time I read it, largely because I found the prose is exceedingly dense. I learned a lot from it on subsequent reads, but I also learned that it was okay to finish a book and say, ‘I just didn’t get that.’

‘The Uninhabitable Earth’ / David Wallace-Wells, The New Yorker

This article radicalised me. I know this is a book list and not an article list, but this piece changed me utterly. I read it only once, on a nondescript evening in March or April last year. It terrified me half to death. I haven’t read it since. It sparked an extended period of climate anxiety, during which time I was convinced there wasn’t gonna be a next year why were all these people making life plans so far ahead didn’t they know the world was ending, but it also galvanised me into seeking the truth. I came out the other end with a very different perspective on ecology, society, and democracy.

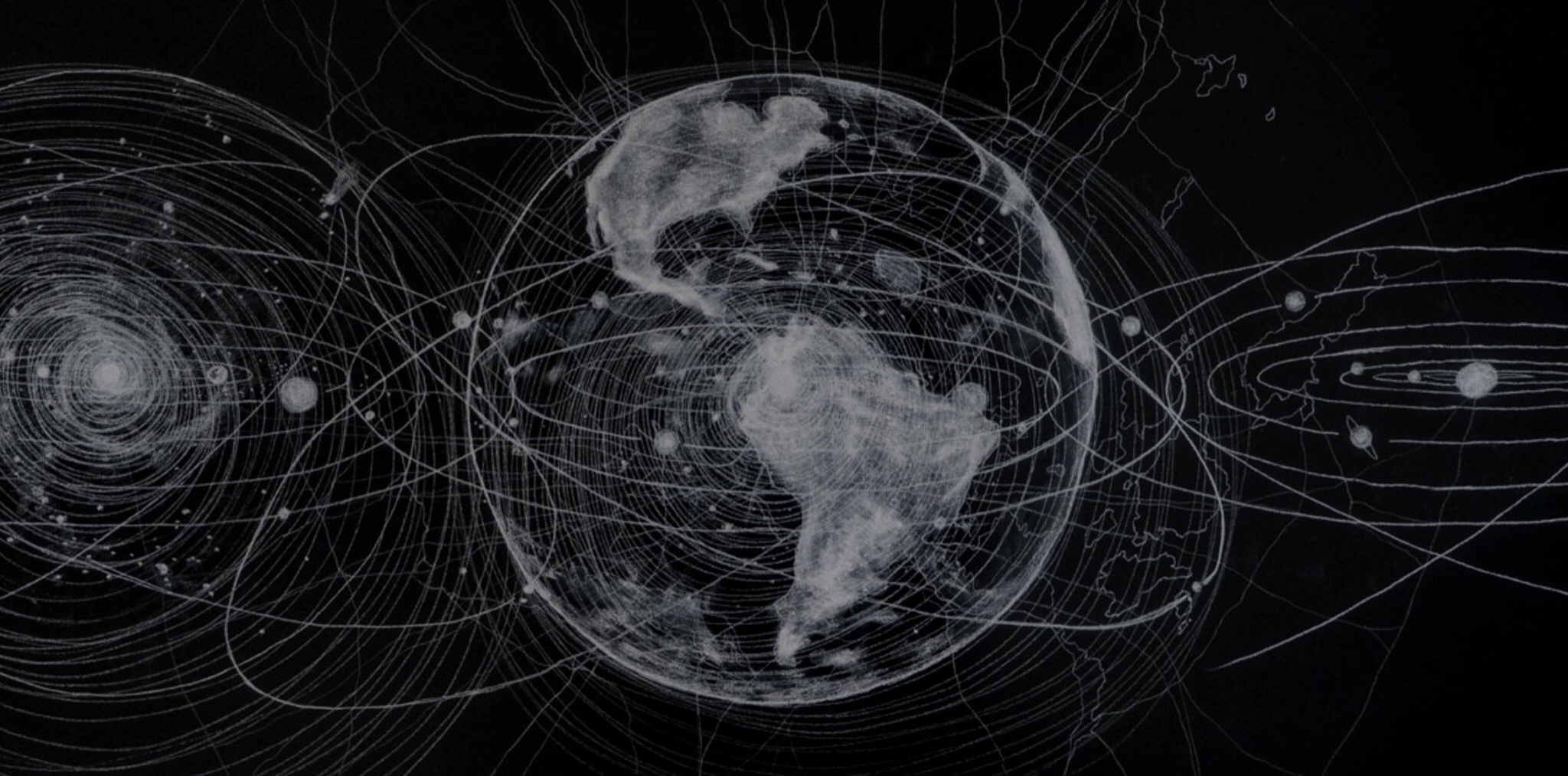

‘Time to a Pin-Oak’ / Katie Holten and Chelsea Steinauder-Scudder, Emergence Magazine

The first five issues of Emergence were published in an enormous print volume so I’m counting it as a book.

I first met the word ‘dendrochronology’ on paper at age four, defined in my favourite compendium of miscellaneous facts as ‘dating by counting tree rings’. Unfortunately for me I didn’t hear the word spoken aloud for another twenty years, so I went around proudly telling everyone about ‘dend-roch-ron-ology’ and how nobody needed a calendar, only a tree. No wonder I got picked on at school.

The word stayed with me, though, and I rediscovered its magic through the magnificent Emergence Magazine, easily one of my favourite things to read, a nourishing blend of ecology, culture and spirituality. ‘Time to a Pin-Oak’ mirrors the birth of the universe with the birth of an oak tree, situating our short lives within the unfathomable vastness of the universe. I find this kind of temporal context deeply grounding and comforting. I love everything about Emergence.

That big report we’ve been waiting for has come out (mb you’ve seen it) / Bailey Sharp

In my head I call this ‘the synoptic zine’ because it has a dark wordless synoptic chart on the cover. I lost my shit the first time I read this. I was deep diving into one of Kassi’s latest zine hauls and I stopped everything and goggled at how real it felt. It’s a greyscale comic about the likely end of the world and how our children and their children, amorphous blobs the lot of them, might cope (or not) with the circumstances they will inherit. It hit me in every feel I had.

This later turned up in my zine cataloguing in-tray at work (it might have been from someone’s Other Worlds haul, but don’t quote me on that). I’ve never catalogued a zine so attentively. I made sure the word ‘synoptic’ was in the record. I’d never find it otherwise.

On anxiety: an anthology / 3 of Cups Press

I find this by turns a harrowing and soothing book, a crowdsourced compendium of contributions from mostly England. It came into my life at the end of 2018, the year of climate anxiety and employment anxiety and illness anxiety. I was a mess. I wanted to be heard, and this book hears me. Sometimes that’s all you can do for an anxious person. To say ‘I hear you’ and maybe ‘I feel this too’ and hopefully ‘You’re going to be okay’.

I resonated with ‘Stress reduction for companion birds’ and ‘(F)logging on’. The comic ‘Me I.R.L.’ is by a librarian. I, too, am often a rainy cloud.