‘Why don’t we just ditch Dewey?’

Well, why don’t we just. After all, it’s a fair question, provocatively asked by a client services librarian at a session of our week-long end-of-year zoom gathering. My heart sank. Of course somebody asked this. A fellow colleague cheekily posted in the zoom chat ‘Your time to shine, Alissa!’ I can’t recall ever meeting him properly, but I guess he knew who I really was? I could see the University Librarian about to respond, as the Q&A portion of the hour was intended for the library executive, when suddenly I found myself interrupting, unmuted, to over a hundred people:

‘Uh, could I just say something here?’

With approximately zero seconds notice I ad-libbed five or so minutes of explanation around this idea, having entirely forgotten to put my camera on. My hands were shaking by the end of it. Surprise public speaking is really not my thing.

Here’s a much fuller version of what I think I said, with some added points that I only thought of after a strong peppermint tea and some chillout time with my fern collection. I know my comments were recorded for an internal audience but I’m deliberately not going back and listening to them! While I’m not a classification expert, I have spent many years agitating for more critical attitudes to this work, and I am the metadata team leader here, after all. If anyone was going to give a (decent) answer to this question, it was gonna be me.

Smart move, loser. Now you’re gonna have to say something!

Shut up, brain.

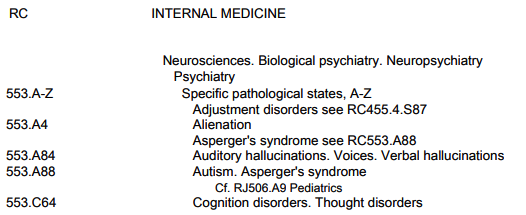

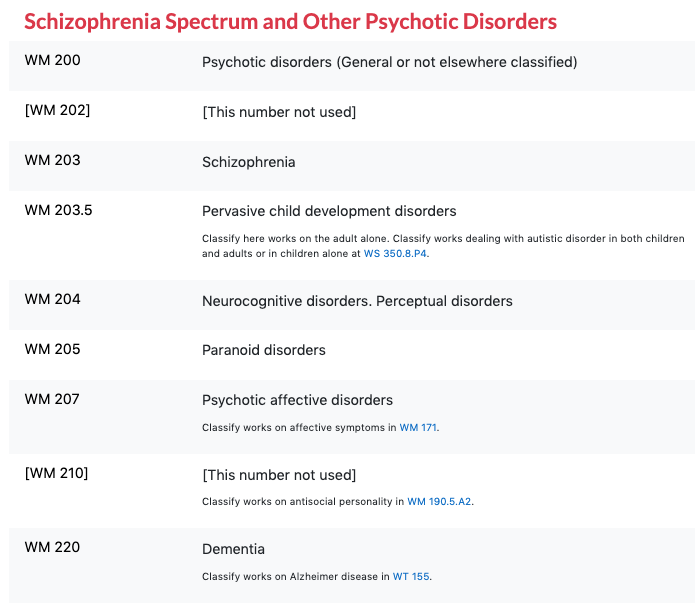

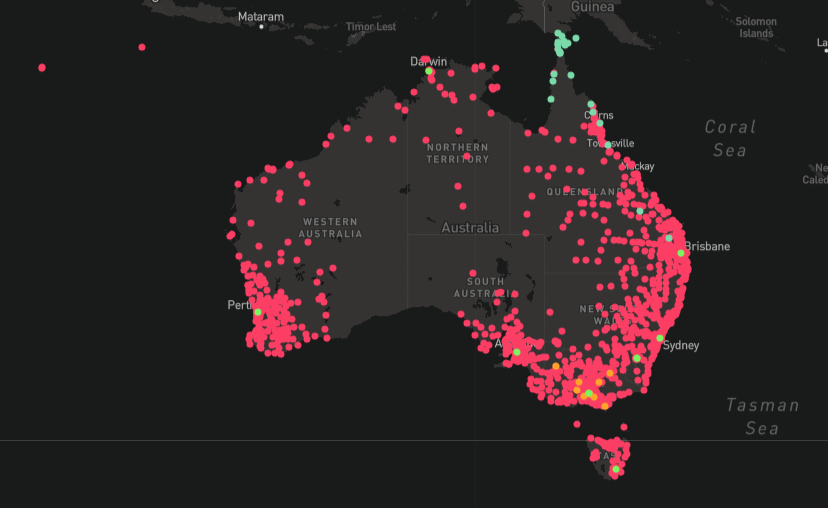

These days, ditching Dewey is no longer an outrageous, unthinkable suggestion. Only 19% of American academic libraries were found to be using DDC in 2018, with that number steadily dropping. The biggest problem now is what to replace it with. If there existed a better classification system for generalist academic libraries like ours, chances are someone would be using it already. I could spend my entire career devising something better and still never be finished – and it’s not like OCLC are resourcing this work for DDC anymore. The only other system in wide use in Australia is Library of Congress Classification (LCC), which isn’t exactly a better option. It encodes the biases, perspectives and priorities of the United States government, just like LCSH does, and why would we want that in our library? The nexus of classificatory power is located far, far away from us, when it needs to be right here. LCC has a tendency to historicise Indigenous peoples—that is, place everything about them in the history section, as if they have ceased to exist entirely—and encodes archaic and offensive perspectives on topics as diverse as Arabic literature and the geography of Cold War-era Eastern Europe.

Genrefication isn’t really an option for academic libraries. Our collections are designed for serious research and study, not recreational reading or other types of lifelong learning; whimsical genres are largely inappropriate for an academic setting. Besides, even public library genrefication projects, such as the one at the flagship branch a stone’s throw from my office, are often built on Dewey’s foundations; the books are shelved in distinct genres, yet continue to use a DDC number as a shelfmark, meaning the substrate logic remains the same but is made impenetrable to a casual browser. It makes the browsing experience more frustrating, because you no longer have the granularity of Dewey to guide you, only a broad category. Academic library users are typically quite focused in their browsing. We couldn’t just say ‘here’s the economics section’ and leave them to it—we need the kind of granularity only a formal classification system can provide.

Our print collections have been largely unavailable for browsing for the best part of two years. We’ve been doing distance education for decades and have a large and growing cohort of exclusively online students. It’s not like a lot of people are actively browsing our physical collections right now. Also, reclassifying an entire print collection fills me with dread! My team of 1.6 FTE are nowhere near resourced enough for such a enormous undertaking – physically retrieving, reclassifying, restickering and reshelving every single print book in our branches would take months and involve huge amounts of work. We just don’t have that kind of capacity.

Besides, is large-scale reclassification truly the best use of my team’s limited time and considerable talents? I feel like there are more immediate and more focused things my team and I can do to improve the cultural safety of our metadata. We could be adding AUSTLANG codes and AIATSIS subject headings to our First Nations materials, overlaying records from Libraries Australia that already feature this data. We could work to contextualise offensive and culturally unsafe depictions of First Nations topics, adding content warnings where necessary. We could work with our Indigenous knowledges institute and our colleagues in the Archives to apply Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels for materials we collectively hold, ensuring their provenance, protocols and permissions are clearly documented.

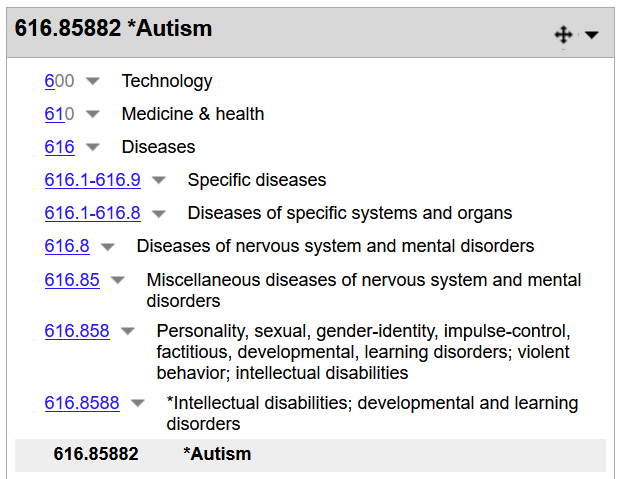

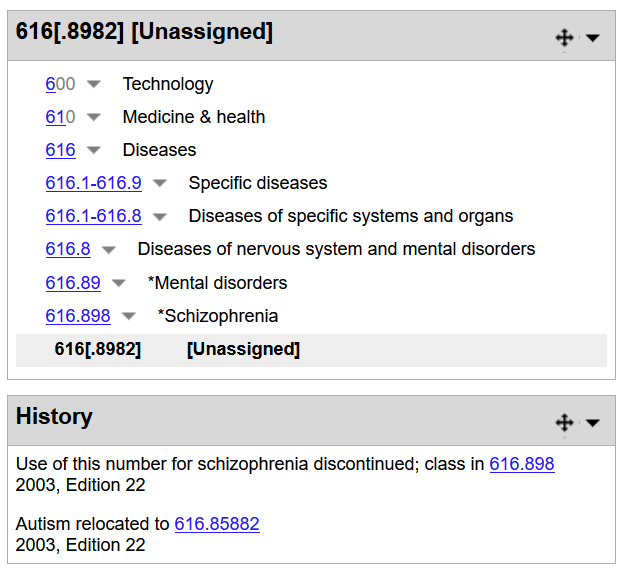

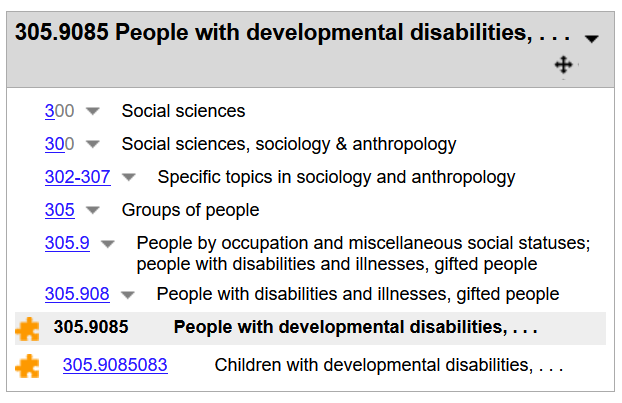

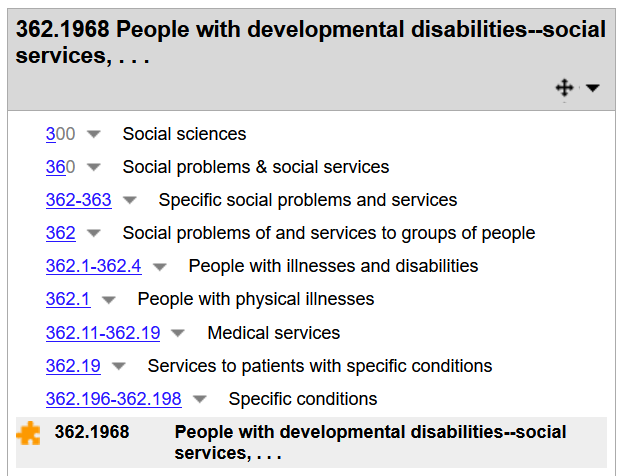

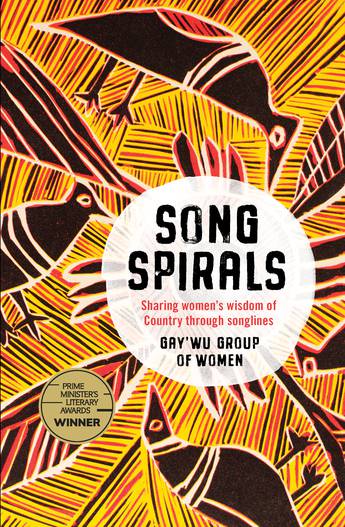

I had a conversation with one of our liaison librarians and her boss a few weeks ago about her campus library shelving First Nations Dreaming stories in 398.2, the myths and fairy tales section. The juxtaposition of core cultural and religious texts with lightweight children’s stories is manifestly inappropriate; the former’s continued placement here, in spite of clear DDC instructions to the contrary since 2003, is a damning indictment of the cultural incompetence of library cataloguers.1 My liaison librarian colleague mentioned this situation in the zoom chat—I suspect it was a surprise to many of our colleagues, including the University Librarian. I responded after I had finished speaking with ‘Absolutely – I look forward to fixing this next year’. I was going to do it anyway but it’s nice to have senior management buy-in for these things 🙂

The Dewey Decimal Classification was designed by a particular man, at a particular time, in a particular place, with a particular collection and for a particular audience. His notoriously questionable values and those of the classification system that bears his name are, by and large, not those we share today. But who is ‘we’? Who gets to put books where? Whose values are encoded and embodied in the placement of books on shelves? What values would our institution like us to project in our physical and digital spaces? What about the multitude of value systems that our students and researchers bring to those spaces? How do we represent such multitudes in a linear shelf arrangement? Should we even try?

Don’t get me wrong, colleagues: I am all in favour of doing classification differently. But please don’t underestimate the difficulty and the sheer amount of work involved. It’s not as simple as just ‘ditching Dewey’.

At this point I ran out of courage and trailed off. The University Librarian, who I get the impression chooses their words carefully, said nothing for a few agonising seconds before inviting a question from another audience member. I had noticed them listening intently as I spoke. I hoped they didn’t mind me interrupting.

Two days later, in another session of our week-long end-of-year zoom gathering, the conversation turned to the ethics of AI, and how systems reflect the biases and perspectives of the people who build them. The UL remarked that the discussion really went to the heart of critical librarianship—recognising that the library profession also has a long history of perpetuating all sorts of biases and harms in our work. And I just about fell off my chair.

Was this real? Did I really work in a library where the University Librarian not only uses the phrase ‘critical librarianship’ in front of the entire staff but makes a point of actively living those values? Did I really hear the directors echo those comments and agree that perhaps it’s time to reconsider our classifiation practices? Did I really hear the UL namecheck me twice in the closing session, for both my colleague’s presentation on our project to fix our batch file loading processes and also for my impromptu Dewey comments? Did I really say all that in front of everybody?!

Truly I feel like I’m working in paradise. It’s one thing to blurt out my Big Metadata Feels in response to a question that wasn’t even directed at me, but it’s quite another for my senior management to embrace these ideals, making a point of publicly supporting the work I do and the things I am so passionate about. Hearing ‘critical librarianship’ out loud at work has just about made my year. Every day I am so grateful to be here. I can’t wait to make good on this promise.

- I did not say this part out loud. ↩