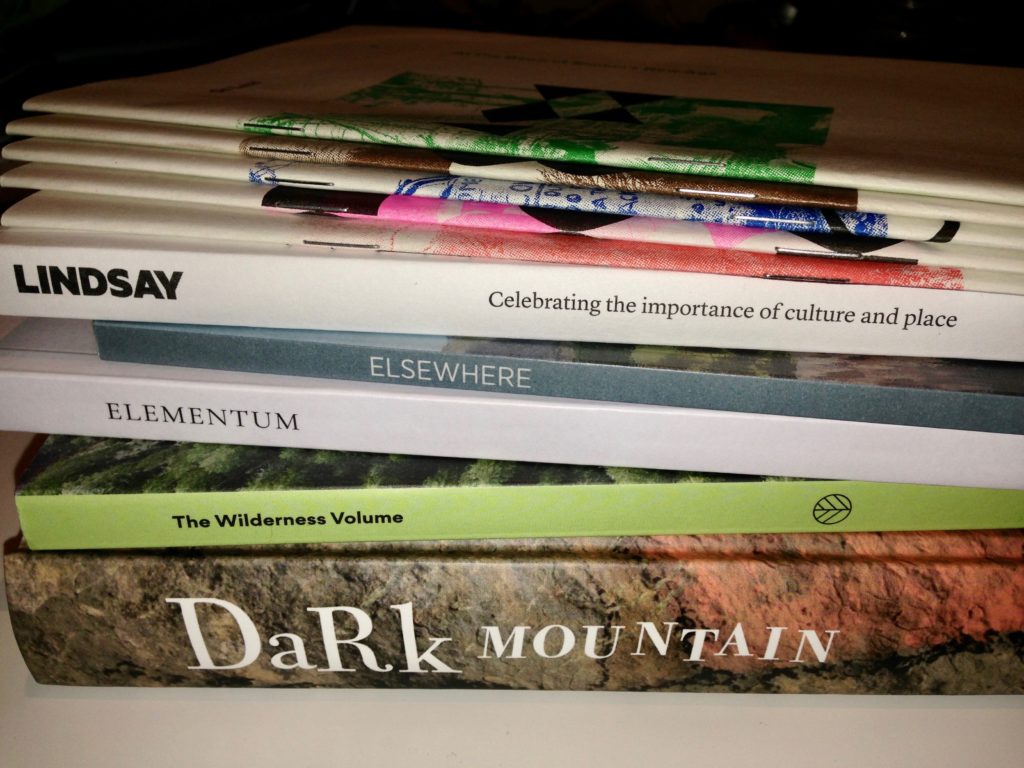

For this month’s GLAM Blog Club theme of ‘collect’, I glanced over at my tottering ‘to-read pile that was sitting on a table but is now a table itself’. It’s perhaps an unusual pile. For one thing, I seldom read novels. Instead I’m drawn to narrative non-fiction, short stories and poetry. Stories about natural history, eco-friendly travel, walking, ecology, place, psychogeography, re-knowing our planet and watching helplessly as it changes. Stories that feel real.

Interestingly, that to-read pile has quite a number of print serials on place and nature writing. (Developing a magazine habit is a bit of a family tradition.) Currently I’m absorbed in volume 4 of Elementum, which arrived last week (don’t ask me how much the postage was!), as well as back issues of Elsewhere, which I hope to write for one day.

I did a brief analysis of my print serial collection in Libraries Australia and found only one title held in any Australian library: the Melbourne-based Lindsay, who have fulfilled their legal deposit obligations with the NLA. Considering the vast majority of these journals are published abroad I’m not terribly surprised. Perhaps when I die, some nature-inclined library here will take an interest in the rest of my collection. Perhaps not.

Then again, it’s not like online nature and place journals are well-represented in libraries either. There are lots of excellent blogs, often written and maintained by one person, as well as lush online magazines that make the most of the browser and create an immersive reading experience. Yet the long-term survival of many is largely dependent on the Internet Archive, which doesn’t quite feel like enough. My current personal favourite online journal is Emergence Magazine, ‘a journal of ecology, culture and spirituality’ with some seriously impressive writing, visuals and web design.

I’ve also been enjoying Plumwood Mountain, ‘an Australian journal of ecopoetry and ecopoetics’. Australian publications of this type seem to be harder to find. I hope that doesn’t mean they’re thin on the ground; perhaps I’m just looking in the wrong places.

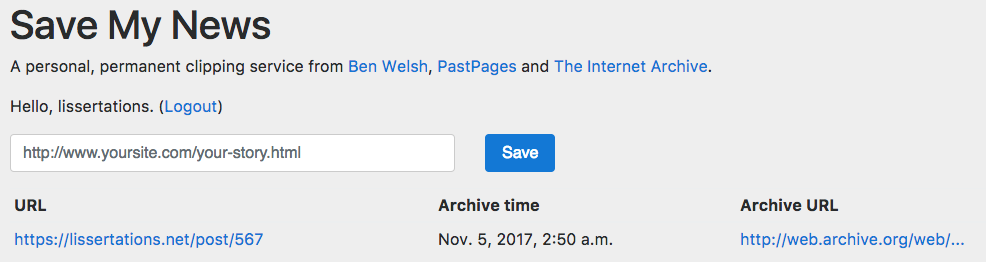

Naturally, I’d like to collect Plumwood Mountain, or hope that a library could do so for me. I have a few options: I can manually save every page to the Internet Archive (highly time-consuming); I can manually save every page locally using Webrecorder (also highly time-consuming); or I can submit the site to Pandora and hope the author acquiesces. If she doesn’t, well, I tried. (Did you know anyone can suggest sites to Pandora for collection? Be aware that if you put someone’s email address in the form, it’ll send them an email.)

How can libraries collect emailed serials? In my past life as a local history librarian we dealt with this mostly by printing them out, which is obviously not ideal. To the best of my knowledge, newsletters hosted on platforms like MailChimp and Constant Contact aren’t harvestable by web archiving crawlers. Collection of these emails by libraries would therefore depend on either the publisher depositing a clean HTML or PDF version, or preserving the email files as part of an archive of someone’s inbox (which is very difficult, highly labour-intensive and not ideal for everyday access). We can’t rely on online platforms being available forever. We need to figure out a way to collect and preserve this content from the browser.

I desperately want someone to archive the full run of In Wild Air, a weekly emailed serial from 2016 to 2018 by Blue Mountains-based creative Heath Killen, each week featuring six things that made a guest tick. I loved this newsletter. Every Monday I took a leisurely walk through someone’s psyche. It was brilliant. I love basically everything Heath does. But if I were to ask Pandora to crawl that website, all it would collect is the index of names. The content itself is hosted on MailChimp—beyond the crawler’s reach.

I wonder if this proliferation of Anglophone ecoliterature is decidedly English in origin—the place, as well as the language. Settlers in Australia brought English concepts of geography with them (as explored in J.M. Arthur’s 2003 book The default country) and tried, unsuccessfully, to apply them to the Australian landscape. How else could you justify calling Weereewa / Lake George a ‘lake’ or Lhere Mparntwe / Todd River a ‘river’?

A collection selection

These are a few of my favourite journals. Please be aware that this list, though reasonably culturally competent, is white as hell. I’d really like to address that. A lot of these are based in Britain, where the nature writing crowd is overwhelmingly white, but I’m very keen to expand my collection to include more Indigenous perspectives. I’d also like to highlight the upcoming Willowherb Review, an online journal for nature writers of colour, which promises to be very good.

Print journals

- Elsewhere : a journal of place

- Elementum : a journal of nature and story

- Lindsay : celebrating the importance of culture and place

- Another Escape : outdoor lifestyle, creative culture, sustainable living

- The Dark Mountain Project, for environmentalists who have given up hope and instead turn to story

- Heath Killen’s On Land zine miniseries

Online journals and blogs

- Emergence Magazine : a journal of ecology, culture and spirituality

- Plumwood Mountain : an Australian journal of ecopoetry and ecopoetics

- The Trumpeter : a Canadian journal of ecosophy

- East of Elveden by English writer Laurence Mitchell

- Write The Map : journeys, territories, writings, mappings

- From Hill to Sea by Murdo Eason / Fife Psychogeographical Collective, Scotland

- Vanessa Berry’s Mirror Sydney (the book is also really good)

- PAN : philosophy, activism, nature

- Bomb Cyclone : a journal of ecopoetics, based in Malaysia and the United States

- Heath Killen’s The Territories (archived by Pandora) and In Wild Air