Australian library catalogues speak American English. This has pissed me off for as long as I can remember (long before I started working in libraries). I want to do something about it.

Thing is, Australian librarians have wanted to do—and have done—something about this for decades. The venerable John Metcalfe thundered about the increasing use of American language, by way of the Library of Congress Subject Headings, in Australian libraries in the late 1960s (‘I have a rooted objection to consulting foreign language catalogues; my language is Australian English’)1. Successive groups of cataloguers and other interested librarians edited and produced two editions of the List of Australian Subject Headings, intended to supplement LCSH, in the 1980s (First Edition of the List of Australian Subject Headings, or FLASH) and early 1990s (Second Edition, or SLASH). Sadly, the ANBD Standards Committee resolved to move away from most of this work in 1998 with the impending move to Kinetica2; Ross Harvey lamented the decline of Australian subject access the following year3.

These days it’s fair to say the Americanisation of our public and academic library catalogues is not a priority for library managers. School libraries, of course, largely use the in-house SCIS thesaurus, designed by Australians for Australians, and certain special libraries such as AIATSIS, ACER and the federal Parliamentary Library maintain their own thesauri. But the publics and academics, where the vast majority of cataloguing is outsourced, cling to LCSH as their primary subject controlled vocabulary. I suspect it’s more out of apathy than loyalty.

Today the Australian extension to LCSH sits on a forgotten corner of the Trove website, quietly gathering dust, the content copy-pasted from the former Libraries Australia website. It has looked like this for at least a decade. Development policy? What development policy?! From experience, the only parts of the extension still in common use are the compound ethnic descriptors (Vietnamese Australians, Italian Australians, etc) and the ability to subdivide geographically directly by state (eg Ducks—Victoria—Geelong, rather than Ducks—Australia—Victoria—Geelong). These local terms are coded as LCSH (ie, 650 #0) even though they’re not.

I couldn’t understand why this crucial aspect of Australian bibliographic culture was (is) being completely ignored. I thought a lot last year about what a solution could look like. I was deeply torn between doing free work for the Americans—that is, pushing for an Australian SACO funnel, which would make contributing to LCSH easier and more accessible for Australian libraries4—and building local vocabulary infrastructure here at home to enable libraries to describe resources for Australian users in Australian English. Neither option is perfect, and each would require a fair bit of work and maintenance.

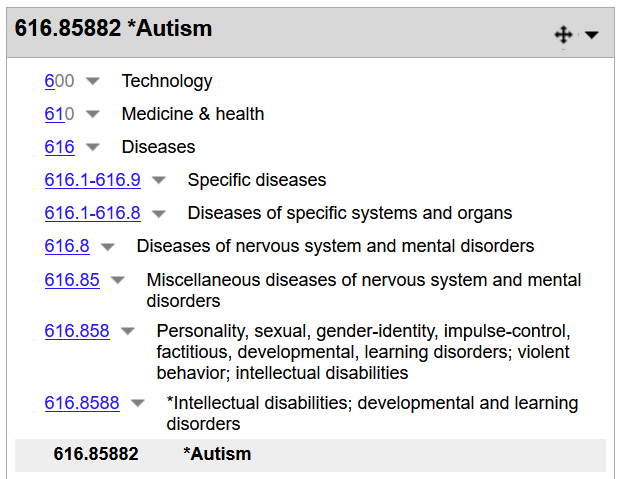

What swayed me towards the latter was remembering that an Australian SACO funnel wouldn’t actually solve the core issue as I see it: LCSH will always use American spellings and American words as preferred subject headings. It might include alternate spellings or words as ‘use for’ or non-preferred terms, but ultimately it will always call things ‘Railroads’ and ‘Airplanes’ and ‘Automobiles’ and ‘Turnpikes’. It will always be compiled for the primary benefit of the US Library of Congress. The status of LCSH as the de facto standard subject vocabulary for Anglophone libraries worldwide is a secondary consideration.

So I thought—what if we brought the FLASH back? What could a revived Australian extension to LCSH look like? I wanted to know where we got up to in the 1990s, how many uniquely Australian terms might be used today, whether it would be worth re-compiling these into a new supplementary vocabulary, and how to encode, host, maintain and govern such a vocabulary for maximum benefit and impact.

One week, fifty-one dollars and 177 scanned pages later, I had a PDF copy of the unpublished second edition of the List of Australian Subject Headings (SLASH) from 1993, thanks to the State Library of New South Wales (the only holding library) and a tip from ALIA. It’s a fascinating glimpse into the early nineties, a time I am too young to remember, with thesaurus terms reflecting Australian society, culture, politics, and bibliographic anxiety about particular Americanisms.

Analysing this document will be quite a task. I am fortunate to have institutional access to NVivo, a ‘qualitative data analysis computer software package’ (thanks Wikipedia) that researchers use for things like literature reviews and analysing interviews. I am not an academic, but I suppose I am now a researcher.

I’m currently tagging (what NVivo adorably calls ‘coding’) thesaurus entries by theme, where there is some overlap:

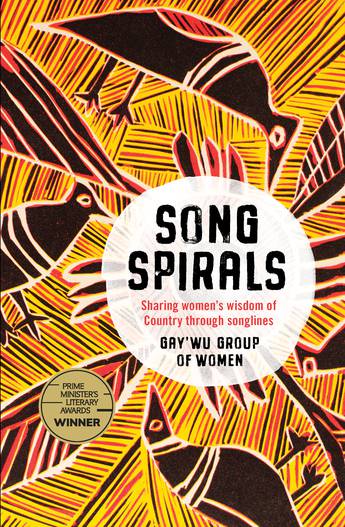

- First Nations people and culture

- Australian plants and animals

- Australian English re-spellings of LCSH terms

- Uniquely Australian terms and concepts not found in LCSH

- Outdated or offensive terms

- Interesting terms for further discussion (this category won’t be included in the final analysis)

First Nations terms would these days be drawn from the AIATSIS thesauri and AUSTLANG. Many terms for Australian nature and culture (such as ‘Mateship’) have since made their way into LCSH proper, and many offensive terms have recently been, or will shortly be, addressed by LC. I want to know what’s left over: how many terms, in which thematic areas, whether it’s worth exploring further. It’s entirely possible that after I’ve narrowed down the list to Australian concepts not yet in LCSH, and Australian spellings that will never be in LCSH, it might not be worth doing anything. I don’t know yet, and I’ve decided I’d like to find out.

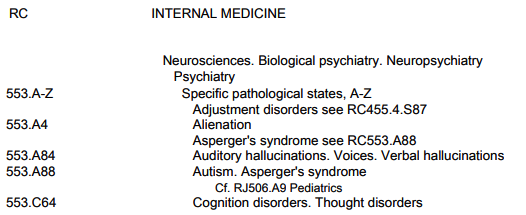

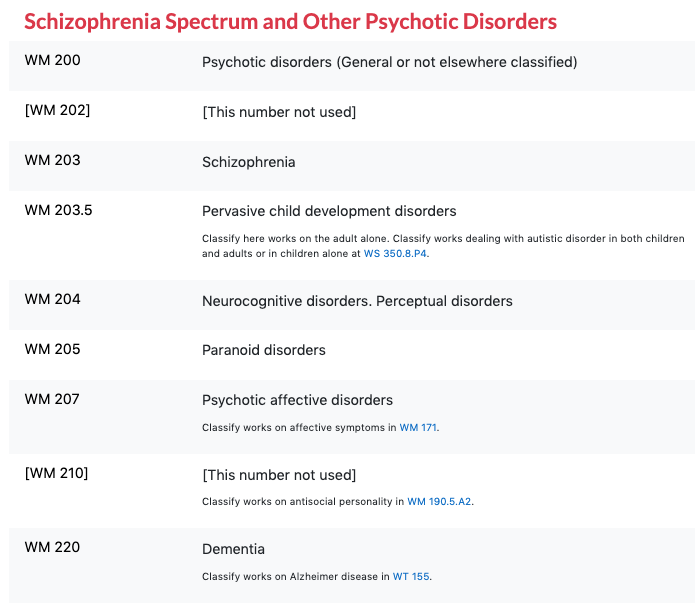

So far I’ve only finished coding the As, but it’s a fascinating exercise. Some choices made in SLASH are still ahead of where LCSH is today, such as the reclamation of ‘Indians’ to refer to people from India5 (the SLASH term for Native Americans has, uh, not aged well). Other choices reflect divergences between Australian and American English that I suspect have since narrowed, such as preferring ‘Flats’ over ‘Apartments’.

Over the next few weeks or so I’ll hopefully code the rest of the SLASH headings and assemble a corpus of data to guide my next moves. I’d love to hear from anyone who likes the idea of a revived Australian extension to LCSH, even if they might not be so sure how their library could practically implement it. Catalogue and vocabulary maintenance is a lot easier now than it used to be (depending on your ILS—some exclusions apply!!) and I’m reasonably confident that we could make something cool happen. We’ll see what the data says…

- Metcalfe, J. (1969). Notes of a contribution by Mr. J. Metcalfe on LC Subject Cataloguing as Central Cataloguing Used in Australian Libraries. Seminar on the Use of Library of Congress Cataloguing in Australian Libraries, Adelaide. Cited in McKinlay, J. (1982). Australia, LCSH and FLASH. Library Resources & Technical Services, 26(2), 100–109. ↩

- Trainor, J. (1998). The future direction for Australian subject access. 45th Meeting of the ANBD Standards Committee. Retrieved January 12, 2023. ↩

- Harvey, R. (1999). Hens or chooks? Internationalisation of a distinctive Australian bibliographic organisation practice. Cataloguing Australia, 25(1/4), 244–260. ↩

- You don’t have to be a member of SACO to propose new or changed LCSH, but I understand that it helps—the form for non-SACO members is missing some crucial detail, such as the correct email address to send it to, and proposers are often not notified about the progress of their submissions. ↩

- For more on this heading, see Biswas, P. (2018). Rooted in the Past: Use of “East Indians” in Library of Congress Subject Headings. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 56(1), 1–18. ↩