And we would go on as though nothing was wrong

And hide from these days we remained all alone

Staying in the same place, just staying out the time

Touching from a distance

Further all the time

I quit my job last Thursday.

I was so excited about it all. I had been offered two (!) positions at two different libraries in Melbourne and had the luxury of choosing between them. I had never felt so employable. I was really looking forward to moving south, being with my friends and support network, having a fresh start. Plus I had tickets to see New Order in Melbourne that weekend. A last quick trip before moving away from the city I’ve lived in all my life.

I excitedly told close friends I had accepted a new position and would be moving soon. They were all so happy for me. I couldn’t wait to join them.

That was ten days ago. Ten years ago. A lifetime ago.

Nothing is real anymore.

It felt like the last gig before the apocalypse.

To be honest I’m surprised it still went ahead, coming the day after the Friday March 13 edict banning mass gatherings of over 500 people. The following night’s show at the Forum was cancelled. I had decided not to go anyway. Outdoors at the Music Bowl felt safer, with more space to distance on the lawn.

There was quite a large crowd, considering. A reporter from Channel Nine was doing a live piece-to-camera as I approached the gates. We were ‘defying the bans’, though they wouldn’t come into effect until Monday. Many attendees seemed relaxed, but I wasn’t one of them. I kept replaying the previous morning in my head, where I had a massive panic attack at the interstate coach terminal about whether I should make the journey at all. I boarded the coach with about thirty seconds to spare. I’m still not sure I made the right choice.

In the last week and a half, and in this order, I have: been made two job offers, accepted one, declined the other, quit my current job, started planning an interstate house move, reconsidered said house move, watched the world fall apart, postponed said house move, asked new job if I could work remotely, unquit current job just in case, received word that new job would let me work remotely, took lots of sick leave, continued to watch world fall apart, remembered new job would be short-term contract with no leave accrued, sadly declined new job, confirmed I could stay at current (permanent) job, and spent a lot of time in bed, at the doctor’s office, and in the throes of anxiety.

It’s been a lot. And I am not coping.

The 2019 novel coronavirus, which causes the disease known as COVID-19, has spread rapidly around the world in a matter of weeks, causing almost unfathomable amounts of social and financial upheaval. Most who contract the disease experience mild illness (noting that the WHO considers pneumonia ‘mild’) and make a full recovery. Some will develop serious illness. A small proportion, currently estimated to be anywhere between 1% and 3.4% of sufferers, will die of the disease.

My mother has severe asthma and a long history of respiratory problems. If she contracts COVID-19 she will be at far greater risk of serious illness. I am petrified that something will happen to her and, given her age and comorbidities, she will likely not be prioritised for treatment in hospital. She deserves to survive this as much as anyone. She is the only parent I have.

It feels in many ways like I am becoming her mother, despite the fact my maternal grandmother is still with us. I just want to keep my mum in her house because she’ll be safe at home, right? Everyone will be safe at home?! Please tell me we will all be safe at home. Home is the only place I feel safe at the moment.

Part of me knows I am less likely to become seriously ill myself. I am young, have a good immune system, and already make a habit of staying away from other people. And yet somehow that doesn’t convince the rest of me, the parts of my brain consumed by firecrackers of anxiety, clutching kernels of truth and spinning around them like Catherine wheels. Every fear a sparkler, every anguish a Roman candle, every explosion ringing in my aching skull.

My director sent me home from work on Tuesday. I haven’t been back since.

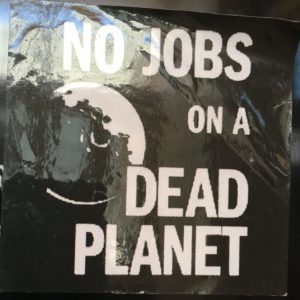

As a library worker, I have the honour—and responsibility—of serving the public. Most of my work is done behind the scenes, but I also undertake reference desk shifts even though my job doesn’t require it. Usually I enjoy these shifts, but the sheer thought of being in a public space at the moment, much less working in one, fills me with inescapable dread. My front-of-house colleagues should not be expected to risk their health at work. We’re not medical professionals. We swore no oath.

I strongly believe all public-facing library services, including those at public, academic and school libraries, should be suspended immediately in the interests of public health. By staying open, a library sends an implicit message that it is still okay for people and students to meet and congregate. That library also risks becoming a disease vector and a breeding ground for serious illness. This should be a library’s only consideration. The harm that staying open could do to our communities right now is greater than the help (computers, bathrooms, reference services) we would usually provide. Surely no library wants to be known as a COVID-19 transmission site.

For me this is a simple decision, grounded in harm minimisation principles and an ethic of care. But I’m not a library manager, and it is evident many libraries still believe they can do both (hint: they can’t). At the time of writing my library remains open, though I suspect that won’t hold much longer, even as the decision to close is not ours to make.

The (American) Medical Library Association issued a powerful statement in support of libraries and library workers, including the crucial sentence: “[T]he MLA Board advocates that organizations close their physical library spaces, enable library staff to work remotely, and continue to pay hourly staff who are unable to work from home.” The American Library Association, after considerable pressure from its members, finally made a similar (if more reticent) statement urging libraries to close: “[W]e urge library administrators, local boards, and governments to close library facilities until such time as library workers and our communities are no longer at risk of contracting or spreading the COVID-19 coronavirus.” And Libraries Connected in the UK (formerly the Society of Chief Librarians) this week came to a similar conclusion: “it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that library buildings should close to protect communities and staff from infection.”

ALIA have so far scrupulously avoided taking a public stance on the issue, instead choosing to remain neutral and create a libguide. While they ‘[support] the decision of organisations to close libraries at their discretion to mitigate risks associated with COVID-19’, they stop short of openly calling for library closures. On Wednesday I finally snapped at ALIA on Twitter, unable to comprehend such an absence of leadership, and imploring the Board to take a stand for the health and safety of library workers and patrons. ALIA consequently released a poster on ‘staying safe in the library’, assuming that libraries would—or should—remain open. It’s fair to say I didn’t respond well to this news.

This is how our library association responds to a pandemic. A poster. Predicated on libraries staying open.

I have never been so ashamed to be an ALIA member. We need leadership. We need public safety. We need library closures. And instead we get this.

#CLOSETHELIBRARIES https://t.co/GFojxxH9qL

— Alissa M. (@lissertations) March 18, 2020

I don’t know why I keep looking to ALIA to demonstrate leadership in the Australian library sector. I don’t know why I hope they will stand up for library workers. I don’t know why I think they will change. The ALIA Board’s statement of Friday 20 March gave the distinct impression they would prefer libraries stayed open. I was very pleased with the result of the recent Board elections, though the Directors-elect won’t take their seats until May, but I’m not sure I can bring myself to keep supporting an organisation that consistently refuses to support its members. My membership is coincidentally up for renewal, as it is every February; I’m currently too broke to pay it in any case, but I really wonder if this is the final straw. Everyone is reconsidering their priorities right now. I wish this wasn’t one of them.

I had expected to spend this weekend preparing to move to Melbourne. My house is full of half-packed moving boxes. I’ve barely unpacked my rucksack from last weekend. I had one foot out the door and one eye on the promised Yarra and now, for now, it’s all gone. It is a crushing disappointment. But I also recognise that in these extraordinary circumstances I am very, very lucky. I still have a permanent job, access to sick leave, supportive managers, a roof over my head, and soup in the cupboard. Many among us, including casual library workers, may now have few to none of those things. Now is the time for solidarity, not selfishness.

I live near a fire and ambulance station. I frequently hear sirens in the distance at all hours. But late at night the fire engines and ambulances often mute their sirens as they pass the flats, in an effort to avoid waking people.

This week has felt as if this country was waiting for the sirens’ call, watching as case numbers rose exponentially, wondering when to make extraordinary decisions that now seem less drastic with each passing day. We had the luxury of hearing the sirens coming. We’ve all seen what happened in Wuhan, China; what is currently happening in northern Italy; and what will surely soon happen in the United States. Yet the virus approached this country like ambulances approach my flat at two in the morning: quietly, then all at once. And we were not prepared.

In the last few hours several states and territories have announced the shutdown of non-essential services, including cafes, restaurants and bars. I sincerely hope this will include public-facing library services. Libraries are an important public space—but not, in these times, an essential one. We owe it to our patrons to not get them sick.

The concert was pretty good, by the way. Bernard Sumner’s vocals aren’t what they used to be, and some will swear it’s not the same without Peter Hook, but the music was quite enjoyable. New Order were the first band I ever saw live. I hope they won’t be the last.

As the crowd made to leave, another song began to play. Another band. Another time.

It’s the end of the world as we know it

It’s the end of the world as we know it

It’s the end of the world as we know it

And I feel fineIt’s the end of the world as we know it

(It’s time I had some time alone)

It’s the end of the world as we know it

(It’s time I had some time alone)

It’s the end of the world as we know it

(It’s time I had some time alone)

And I feel fine