This is the working transcript of ‘We need to talk about cataloguing’, a talk I gave at the 9th New Librarians’ Symposium in Adelaide, South Australia on Saturday 6th July 2019. I made some last-minute edits to the text and said a few things in the wrong order, but overall I pretty much stuck to script (which was very long, hence my conscious decision to talk too fast!).

The slides on their own are available here (pdf). Inspired / shamed by Nikki Andersen’s brilliant talk at NLS9 ‘Deviating with diversity, innovating with inclusion: a call for radical activism within libraries’, all the slide pics also include alt-text.

Thank you. I begin by acknowledging the traditional and continuing owners of the land on which we meet, the Kaurna people, and pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging. This land always has been, and always will be, Aboriginal land.

Library workers, students and allies, we need to talk. You’ve probably heard of this strange thing called ‘cataloguing’. You may even have met some of these strange people called ‘cataloguers’. But for many people in the library sector, that’s about all we can say. Many of us don’t have the vocabulary to be able to talk about areas of library practice that aren’t our own.

It’s not quite the talk I promised to give, but it’s a talk I think we need to have. About what this work entails, why it matters, and why you should care. Consider how, and to whom, we should start talking. Our colleagues, our supervisors, our vendors, ourselves.

My name is Alissa McCulloch. We need to talk about cataloguing.

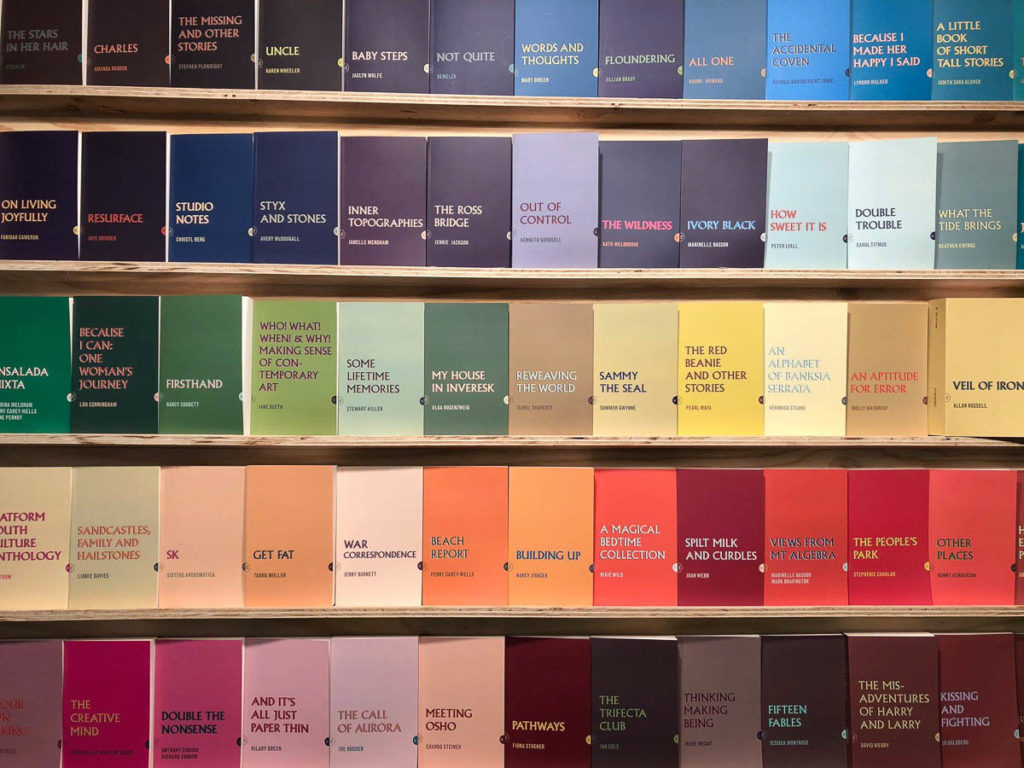

(By the way, this is a real book, and it’s awesome.)

Firstly, a bit about me. I work at a small, minor national library that shall remain nameless, because I’m not speaking on behalf of my employer today (I just need to make that very clear, these are all my opinions, not theirs). I’ve been in libraries for around four years and have had a library degree for around six months. My work life consists mostly of cataloguing whatever turns up in the post.

You may have seen or heard me talk about cataloguing ad nauseam on podcasts, on my blog, or on twitter, because I LOVE CATALOGUING and it sparks SO MUCH joy and I think it’s amazing. Suffice to say my reputation precedes me. So perhaps some of what I’m about to say will not be a surprise to you. But I am surprised, quite often, by the reactions I get when I tell people what I do all day.

They go ‘Oh… is that still a thing?’ And I’m like ‘Yes, actually, it is still a thing’. People act like metadata grows on trees, that carefully classified shelves of books are ‘serendipitously’ arranged, that cataloguing is obsolete, that structured metadata is unnecessary in an age of keyword searches, that we’ve all been automated out of existence, that AI is coming for the few jobs we have left.

People ask, ‘Why store data about an object, when you have the object itself?’ And I go, ‘Because without data about the objects contained in a space, any sufficiently complex space is indistinguishable from chaos.’

It’s more than just ‘data about data’. It gives meaning and structure to a collection of items, whether that’s a simple website, Netflix, a corpus of research data or a library catalogue. Metadata forms a map, a guide, a way of making sense of the (in many cases) enormous collection of resources at a user’s disposal. A chaotic library is an unusable library.

‘Cataloguing’ doesn’t just mean painstaking creation of item-level metadata (although it can involve that, and it’s what I spend a lot of my time doing). It involves a lot of problem-solving, detective work, ethical decisions, standards interpretation, and data maintenance. If you like puzzles, you’ll love cataloguing. Modern metadata is all about connections. It’s relational, it’s often processed at great scale, it’s about making collections accessible wherever the user is.

You might hear these jobs described as ‘metadata librarians’ or similar. If given the choice, I would describe myself as a ‘cataloguer’. In fact, at my current job no one ever actually told me what my job title was, and I needed an email signature, so I picked ‘cataloguer’ and nobody seemed to mind.

But I specifically didn’t call this talk ‘We need to talk about metadata’. Don’t get me wrong, I could talk about metadata all day, but I deliberately said ‘We need to talk about cataloguing’. The word’s kinda gone out of style. It’s old-fashioned, it’s a bit arcane, it’s not hip and modern and contemporary like ‘metadata’ is. But I’m the sort of person who likes to reclaim words, and I can reclaim this one, so I do.

Words mean things. But sometimes, if we want to, we can change those things.

Once I’ve explained what I do for a living, people then go ‘That’s great. Why should I care?’. And it’s a good question. Why should you care? You’re all busy. You all have other jobs. You don’t have time to care about metadata.

You know why you should care?

Because ‘if you care about social justice or representation in libraries, you need to care about library metadata and how it is controlled’. I know how deeply many of us care about social justice in libraries. We want our spaces and services to be accessible, equitable and empowering to all users. This includes the catalogue. For many users, particularly in academic and TAFE libraries, the library’s online presence will often represent someone’s first interaction with the library. How does your library present itself online? If people go looking for resources about themselves, how will they see those resources described and contextualised?

A while ago I’d sat through one too many team meetings where someone described us as ‘just a processing team’ and vented on twitter, as is my style. I said,

‘Cataloguing is more than merely ‘processing’ an item. Metadata gives voice to collected works, brings their form and meaning to the surface of discovery, so that collections might be found and enjoyed.’

For some reason, a library vendor in California took this tweet and made a shareable graphic meme thing out of it. I stand by what I said, but what really got me was that they left out the best part of the quote. The line immediately after this was:

‘Cataloguing is power, and I will die on this hill!’

We as cataloguers have, as Hope Olson famously put it, ‘the power to name’. We decide what goes where, what’s shelved together, what’s shelved separately. We describe these things in the catalogue so that people can find them. The language used in and about cataloguing is tremendously important. If something is poorly-described, it might as well be invisible, both on a shelf and in a search engine.

Cataloguing is power. That power must be wielded responsibly.

‘In terms of organisation and access, libraries are sites constructed by the disciplinary power of language.’ Now you can read ‘disciplinary’ two ways – once in the sense of an academic discipline, and again in the sense of punishment. Both of them relate to the wielding of power.

As humans, we are all shaped by language. Our everyday language changes through time, as social and cultural practices change, but library language changes far more slowly, when it changes at all. (We’ve been putting punctuation in weird places for a long time, too. Look, I’m sorry, but I will never care about where to put a full stop in a MARC record.)

Metadata is not fixed. Metadata is never ‘finished’. Metadata is contextual. Contested. Iterative. Always changing. ‘Corrections’ are not, and can never be, universal. An accepted term today might be a rejected term in thirty years’ time, and the process will begin again. The Library of Congress Subject Heading (LCSH) for ‘People with disabilities’ is now on its fourth iteration, as the preferred language has changed over time. Previous versions of this heading used terms that would now be considered quite offensive.

We all need to look out for these things. Have new concepts arisen for which your library has no standardised heading? Has a word shifted meaning, such that it has ceased to be meaningful? Are users looking for resources by name, but finding nothing in our collections? Think of the power we have. Think of how we ought to wield that power.

‘When an item is placed in a particular category or given a particular name, those decisions always reflect a particular ideology or approach to understanding the material itself.’

What do I mean by that? Consider the widespread use in the English-speaking library world of Library of Congress Subject Headings, a standardised vocabulary originally designed by American librarians to meet the information needs of the United States Congress. Because the Library of Congress is the source of a lot of American copy cataloguing, their subject headings were widely adopted in the US, and later by other Anglophone countries. Most (though not all) Australian libraries use LCSH in some capacity. Has anyone stopped to think about how weird that is? We’re not the US Congress. We use different words and different spellings, we serve vastly different communities, we have our own information needs and information contexts that LCSH necessarily cannot meet.

Yanni Alexander Loukissas recently wrote a book titled ‘All Data Are Local’, which is sitting on my bedside table at home. I would extend that to ‘All Metadata Are Local’. And they should be. Each library serves a distinct community of users. Our metadata needs to speak their language.

Attitudes toward cataloguing itself are shaped by the language we as cataloguers use to describe our work. For example: a big part of cataloguing is about standardising names and subjects, and to a lesser degree titles, so that resources with or about those things can all be found in the one place! We call this authority control, which has gotta be one of the worst phrases in librarianship for two reasons:

A) whose ~authority~ is this done under? Who died and put us in charge? What gives us the right to decide what someone’s name is, or the best phrase to describe a certain topic? Why do we even have to choose just one? Why can’t we have several, equally valid terms?

B) Why do we have to ‘control’ everything? What need is there for this giant bibliographic power trip? Why can’t we let people decide these things for themselves, instead of us being authority control freaks?

This phrase says a lot about how we’ve historically thought about cataloguing: that we have authority, and that we are in control. Cataloguers haven’t been either of these things for a while. Which is great, because our survival depends on it.

The outlook I’ve just described, and the outlook I bring to my work, is known as radical cataloguing. It’s a way of looking at cataloguing and metadata from a structural, systemic standpoint. Getting to the root of what—and who—our data is for, and making sure it meets our users’ needs.

It’s broadly similar to the contemporary movement called critical librarianship, of which critical cataloguing is a part, which aims, according to the critlib.org site ‘to [bring] social justice principles into our work in libraries’.

Critical and radical cataloguing can involve establishing local policies for catalogue records, working to improve common standards and practices, sometimes ignoring those standards and practices, and encouraging critical viewpoints of—and within—the catalogue.

It sounds quite cool, calling myself a radical cataloguer. But this work and this ethos have never felt all that radical to me. It feels normal, to me. It feels like common sense. It feels like bringing my values to work. Sometimes these align with traditional library values. Sometimes they don’t. But it’s all in the service of making the library better. Think of it as ‘evidence-based whinging’. It’s done in good faith, and it’s done for a purpose.

Sadly, common sense isn’t as common as I’d like it to be. A recent article on tech news website The Verge described the terrible quality of metadata in the music industry, which meant people weren’t getting paid royalties for music they had written, performed, or contributed to. Bad metadata literally costs money. The author described metadata as ‘Important, complex and broken’. And I was like ‘yeah… I feel that’. A lot of what they said about commercial music metadata could just as easily be applied to the library world—infighting, governance issues, funding challenges, cultural differences and copyright laws.

This work is difficult, painstaking, often invisible and mostly thankless. But the results of not doing the work can be slow to manifest—you might be able to get by on deteriorating metadata quality for a while, but soon enough it’s gonna be a huge problem that will cost lots of money to fix, which you could have avoided with enough care, attention and maintenance.

In their recent paper Information Maintenance as a Practice of Care, which I highly recommend reading, the Information Maintainers Collective wrote, ‘Information infrastructure, like all infrastructure, only becomes visible upon breakdown—as in frozen pipes or rifts between institutions. This reality often means that the people maintaining those infrastructures are also invisible.’

It’s not about simply following rules and standards because that’s just how we do things, or have always done things. It’s about imbuing our information practice with an ethic of care. Thinking not just about what we do, but how and why we do it. Who benefits, who loses out, and what happens when and if the work stops being done. The ‘we’ in this instance is an information maintainer: a cataloguer, an eresources manager, a systems librarian. People. Not robots.

People often try to replace me with a robot. They ask, sometimes innocuously and sometimes not, ‘But what about AI and machine learning?’

And I go, ‘It’s a great tool. But like any tool, it has to be used responsibly.’ Algorithms are as biased as the people who write them. We all have biases, we all look at the world a particular way. The key is ensuring that library automation of any kind is properly supervised and evaluated by real people. Metadata professionals with an ethical grounding. Cataloguers, of the past, present and future.

At last year’s IFLA conference session on ‘Metadata and Machine Learning’, researchers from the National Library of Norway talked about their algorithm that assigns Dewey numbers ‘with increasing accuracy’. To them this means longer numbers, which isn’t quite how I would evaluate accuracy. But the point is: this algorithm is following existing rulesets on how to assign Dewey numbers. Think about: who makes those rules? Who designs Dewey? What does our continued use of this particular classification say about contemporary library practice?

Dewey is a product of its time. But it’s also a product of our time. Dewey is now in its 23rd edition, maintained by paid staff and volunteers from around the world. AI can’t do this. It can’t write its own rules. And it can’t be left unsupervised, because it won’t produce quality metadata.

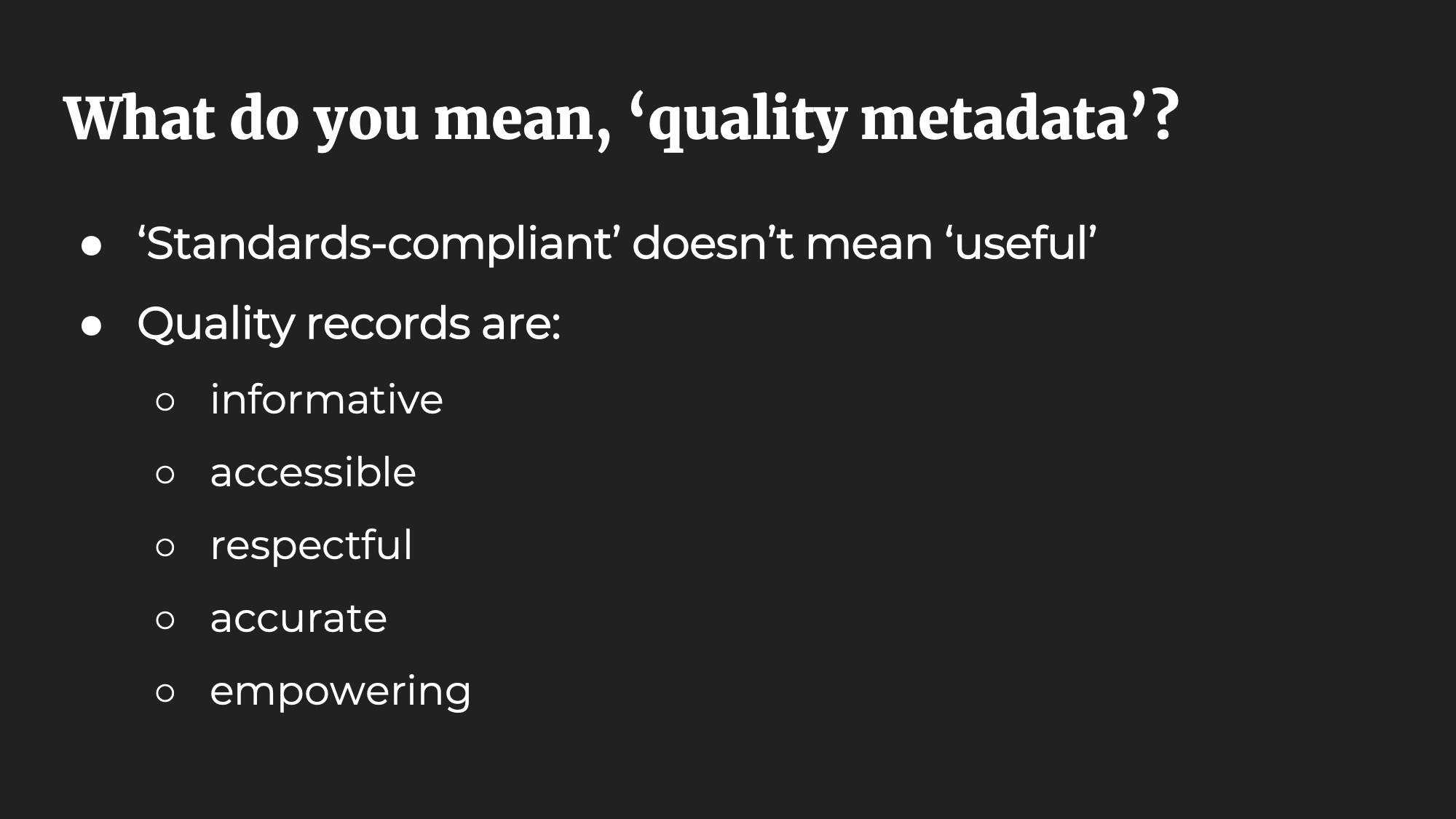

What do I mean when I say ‘quality metadata’?

I don’t think about ‘quality’ the way most other people think about ‘quality’. People think ‘quality’ means total adherence to local, national and international policies and standards. A record can do all of those things and still be functionally useless. I don’t consider that ‘quality’.

To me, a ‘quality’ record is informative, accessible, respectful, accurate and empowering. You won’t find these ideals in RDA, or in the MARC standards, or in BIBFRAME. You’ll find them in your community. Those of you who work in libraries should have an idea of the kinds of materials your patrons are looking for, and how your library might provide them. Is your metadata a help or a hindrance? Are you describing materials the way your patrons might describe them? Are people asking you for help because your catalogue has failed them?

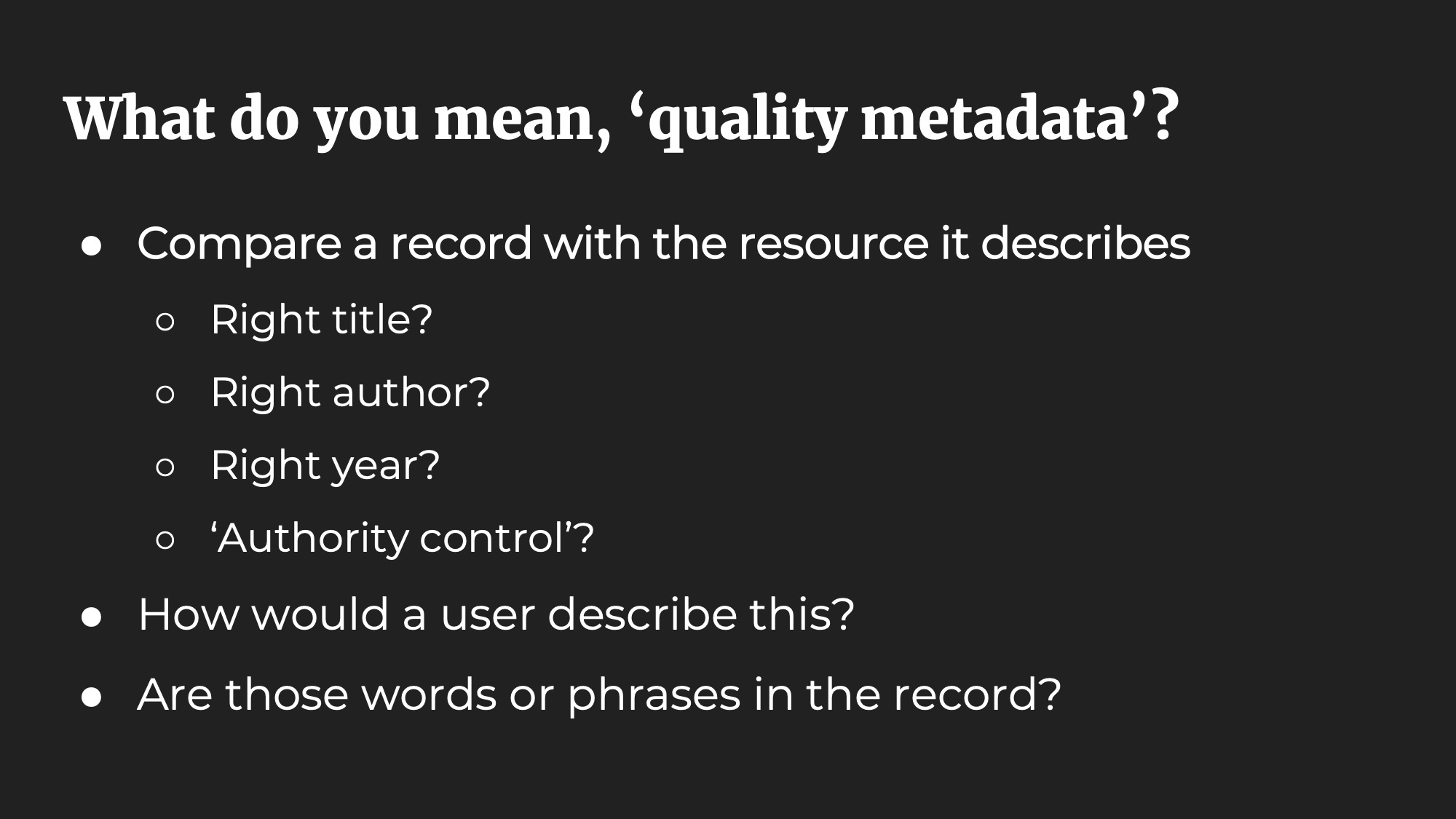

I know most of you are not cataloguers. Many of you undoubtedly work for libraries that outsource most or all of their cataloguing. Records appear in your system by what looks like magic but is probably a Z39.50 connection. You may well have no way of knowing what constitutes ‘good’ and ‘bad’ metadata. Here are some brief tips for you!

Compare a record with the resource it describes. Are the title, author and year correct? Does your system disambiguate different authors with the same name? I know I said I hate the phrase ‘authority control’, but you still gotta do it, the work still needs to be done. How would a user describe this item? Are those words or phrases in the record? What kinds of people use your library? Will these words meet their needs? Are they current? Offensive? Relevant?

Next, compare that record with how your OPAC displays it. Backend versus frontend. Have a look at a MARC record, even if it looks like a bunch of numbers and dollar signs. Is anything obviously missing? Are there MARC fields that your OPAC displays oddly, or not at all? Have a play around with the OPAC. Are some fields searchable but not others? Does your system support faceted browsing, like Trove does? If so, what facets are available?

I once worked for a library whose ILS didn’t display the 545 field, used for biographical and historical data in manuscript records. I’d been using this field for months. Why didn’t I know that my ILS did this stupid thing? How might I have worked around it?

If any problems appear with your library’s data, think about how you might advocate for getting them fixed…

Because the thing is, ‘Tech services work requires a certain comfort with ambiguity and fearlessness in the face of power, that needs education to understand why our jobs are important.’

We are constantly having to advocate for our jobs. I’m doing it right now. Right here, with this talk. And not just because my contract is up in two months and I need all the help I can get. But because without people like me shouting from the rooftops, our work is practically invisible. We are the people behind the curtain. We have to keep telling managers why quality metadata matters. But I am only one person, and I can only shout so loud. Cataloguers need your help, gathered library workers, students and allies, to talk about cataloguing.

So what should we say?

The key is to mind your language.

Firstly, what can you think about?

How does bad metadata make your job harder? What kinds of questions do you get asked that better metadata would be able to answer? Such as: ‘A friend recommended a book to me, I can’t remember what it was called, but it was blue, and it had birds on the cover. I think it was set in Queensland?’ We don’t routinely add metadata for a book’s colour in a catalogue record, it’s not searchable, but people ask questions like this all the time. Perhaps AI could help us with this metadata…!

Secondly, what can you talk about?

Appeal to your managers’ financial sensibilities. ‘Hey, we spent a lot of money on these materials. If people can’t find them, that’s money down the drain. Good metadata makes those materials findable: it’s a return on investment.’ Talk about how much time and effort is wasted dealing with bad vendor metadata, and how that staff time could be better spent on other metadata tasks. I’m sure you’ve got plenty.

Alternatively, appeal to their morals and sense of social justice. If they have one. You could say, ‘We have a lot of refugees and asylum seekers in our community, and books about people in this situation often use the phrase “Illegal aliens”. This sounds kinda dehumanising to me, do we have to use this term?’ And if they say ‘But it’s in LCSH, and that’s what we follow’ you can say ‘well… so? Just because LC does it, doesn’t mean we have to’. You can change that subject heading locally to whatever you want, or get your vendor to do it. It’s already happening in American libraries. It could just as easily happen here.

Being a radical cataloguer doesn’t mean rewriting a whole record from scratch—if good copy exists, it makes sense to use it. But do so with a critical eye. How will this metadata help my users? How will it help my colleagues do their jobs in reference, circulation, instruction or document supply? Is it fit for purpose?

And lastly, what can you do?

Make suggestions internally and externally about what problems could be solved with better metadata. What kinds of patrons ask what kinds of questions or search for what kinds of materials. What your catalogue doesn’t include. What it could start including.

For example, you could encourage your cataloguers and/or vendors to include Austlang codes in records for materials in or about Australian First Nations languages. You could also encourage your systems librarian / ILS vendor to incorporate guided searching or faceting based on these codes into your system, for an even better user experience.

If everything I’ve talked about sounds fascinating and you want more, consider joining ACORD, the new ALIA Community on Resource Description. It’s so new it doesn’t quite exist yet, but it’s slated to launch later this month, and there’s an article about it in the July issue of InCite. I’m hoping ACORD will be a great forum for cataloguers and metadata people to meet, exchange ideas, and work towards better cataloguing for all.

It can be hard to make these kinds of suggestions in your workplace, much less change international rules and standards. But you can do it. You can be part of this change. And the first step is talking about it. If you have an opinion on anything I’ve spoken about today, get talking, get writing, get tweeting, get involved with ACORD, which liaises with the committees overseeing all these rules and policies.

These rules were made by people. They can be changed by people.

And if the rules aren’t working for you, break them.

Change has to start somewhere. So it can start with you.