A handful of Wednesdays ago I quit my job at a mildly prestigious library that shall remain nameless, after just over three years of employment. I wore my favourite cataloguing-themed t-shirt to work, bought one last book with my staff discount at the bookshop, and treated myself to a final helping of bain-marie slop at the cafeteria across the road. It still doesn’t seem entirely real that I’ve left. I still had so much to do.

The last six months have been the happiest and most fruitful of my entire career. I’ve absolutely loved being a systems librarian. I’ve had great fun crafting Access queries, running Perl scripts, devising Excel macros and more, while running complex data reports and conducting bulk data edits for business areas. I learned a heck of a lot about how data and systems work together (or not). But more than anything I’ve really loved my team. They’ve been wonderful people to work with, and I wish them every success.

I was a little surprised by how much time I spent saying ‘thank you’ during my last week. I’m not sure I expected to feel quite so grateful at the conclusion of my time there, but I guess I had a lot of complex feelings about the whole thing. Besides, it turned out I had a lot of people to thank: my wonderful boss Julie, my colleagues Sue and Brad, my director Simon, my previous director Libby, my old boss Cherie, good people like Ros H and Ros C and Catherine.

I wanted to finish that job feeling like I achieved something of lasting value. Instead I settled for starting something that will outlive me and hopefully become standard practice. Sure, helping implement a new service desk ticketing system was useful from an internal workflow perspective, but it’s not quite what I went there to do. Instead I called a meeting with a bunch of managers (well, my boss called it for me) to highlight several pieces of egregiously and systematically racist metadata in our catalogue, mostly relating to Indigenous Australians. Some of the old subject headings hadn’t been updated to the current terminology, while other headings should never have been in our catalogue in the first place. I outlined how my team could remediate these problems, but some policy decisions needed to be made first—ideally by those attending the meeting.

It’s a shame this meeting wound up happening on my last day. But the looks on the faces of my Indigenous colleagues convinced me I was doing the right thing. These terms should have been nuked from the catalogue twenty years ago, but the next best time to do that is now. I kinda felt like this shouldn’t have been up to me, a systems librarian, telling a roomful of people who all outranked me how to fix a data problem. But it needed doing, and I was in a team that had the technical ability to make the necessary changes. I regret that I won’t be around to see them happen.

Shortly after this meeting my director Simon was regaling us with an anecdote about longitudinal datasets; he has a background in statistics and often compares library metadata to things like the HILDA survey. But the key difference is that while HILDA’s questions and expected answers have changed over time in a discrete fashion, making it easier to see where such changes have occurred, library metadata corpora are a total mismash of standards and backgrounds, with each MARC field potentially having been added at a different time, in a different socio-cultural context, for a different purpose. Metadata librarians are grappling with the ongoing impact of data composition and recording choices made decades ago. We have virtually no version control (though it has been suggested) and little holistic understanding of our metadata’s temporal attributes. It makes retrospective #critcat efforts and other reparative description activities a lot harder, but it also hinders our ability to truly understand our descriptive past.

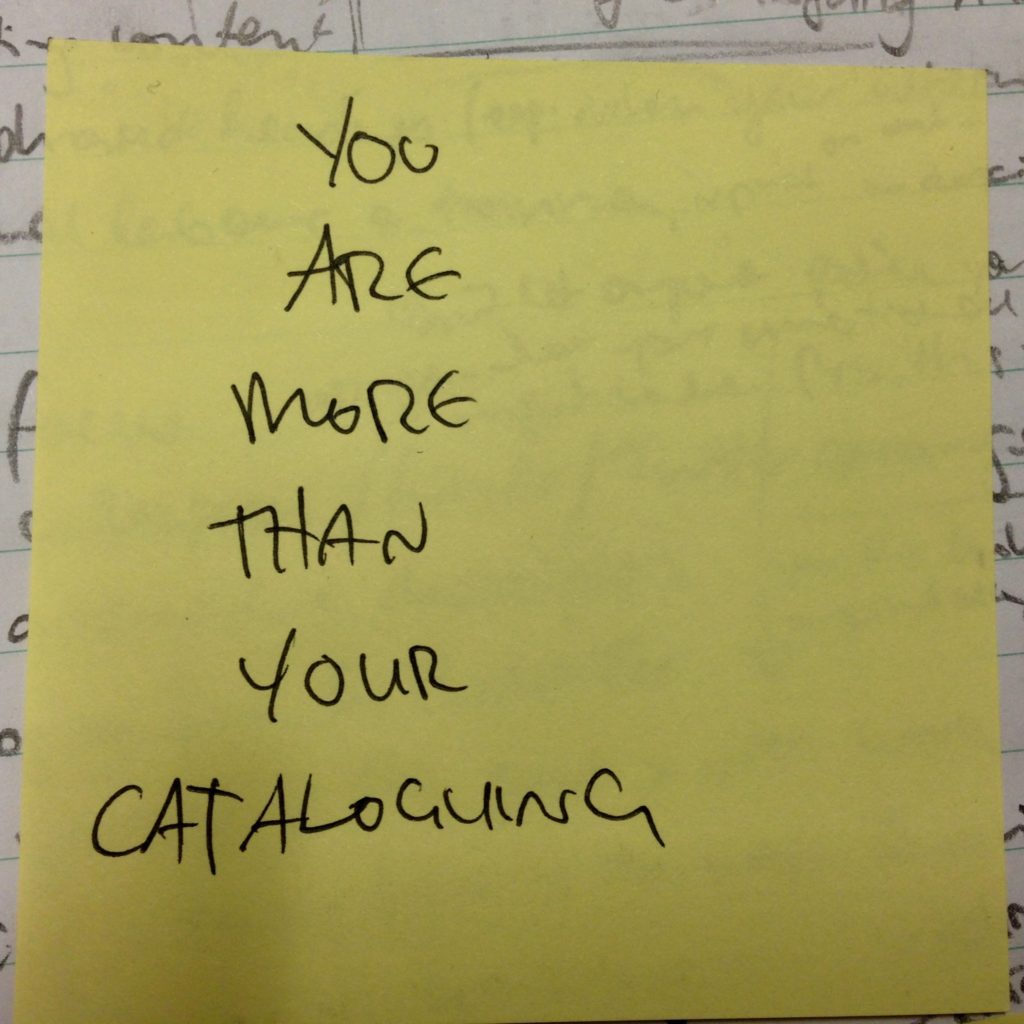

I was pleased to end my time there on a constructive note. But like I said, I have a lot of complex feelings about the last three years. I started out being one of those bright-eyed and bushy-tailed new professionals who didn’t have a whole lot else going for her, wanting to prove her passion and devotion to her dream job by working herself to death, thinking that maybe her job would start to love her back. Please don’t do what I did. I might not have realised at the time how harmful this mindset is, but I also did not realise that I deserved better from an employer. Whenever I think about my time there—barring the last six months—I can’t shake these feelings of deep unhappiness. I feel like I was thrown in the deep end right at the start and spent years desperately trying not to drown. I started thinking nobody would care if I did drown. I was lucky that the restructure threw me a life raft, but the damage was done.

Happily, I have much more to look forward to now. After a pandemic-induced false start I’m finally fulfilling a lifelong dream to move to Victoria, to be closer to friends and forests, and to take up a role as a metadata team leader at a regional academic library. Professionally I feel like I’m returning to my metadata spiritual home, and I like having the word ‘quality’ in my new job title. The ‘team leader’ part is slightly intimidating though—I have no supervisory experience whatsoever (and they know that) but it’s something I’m very keen to do right. Everyone I’ve met there so far has been really lovely. I can’t wait to start next week.

I’m glad to be ending this rather turbulent chapter of my life and beginning a new, hopefully calmer one. I took this job for many reasons, but I keep coming back to the potential I sensed in it. There’s so much possibility here. It’s very exciting.