Everyone, justifiably, wants to see themselves reflected in their library’s classifications. But the two major classification systems used in Anglophone libraries—Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) and Library of Congress Classification (LCC)—as well as the (American) National Library of Medicine classification (NLM) have a long history of reflecting the biases, perspectives and limits to knowledge of the times and spaces they were first devised. Sometimes small aspects are updated, but structural biases are baked in, and far harder to fix.

The following outlines the treatment of autism spectrum disorders in these three major classification systems. None of them are sympathetic to the neurodiversity movement, and range from the benign to the downright offensive. It’s an insight into the history of social and medical attitudes toward autism, but a classification system is not the right place to be storing that history. I wish we could move with the times.

Dewey Decimal (DDC)

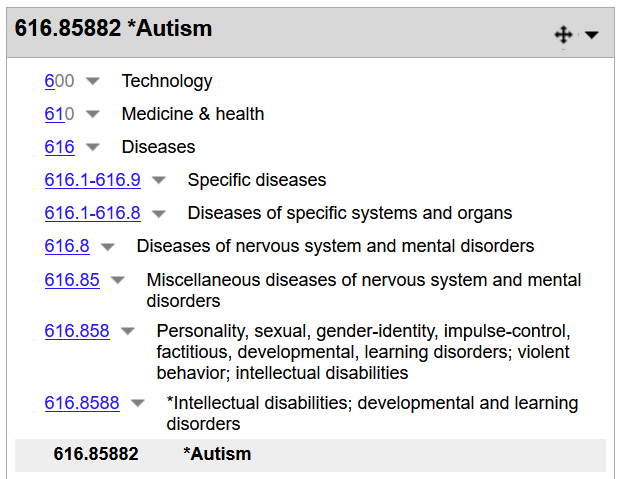

Works on the medical aspects of autism are classed at 616.85882, under ‘Intellectual disabilities; developmental and learning disorders’. This is how the medical establishment sees us, so therefore this is how Dewey sees us. The broader number 616.8588 sits between factitious disorders (including Munchausen syndrome) and ADHD, and is itself part of a grab-bag of socially-marginalised disorders at 616.858 that also include personality disorders, gender-identity disorders and ‘disorders of impulse control’. Can’t say I love this particularly pathologised perspective—and that’s even after looking the other way at ‘Diseases’!

The scope note reads: ‘Class here comprehensive works on pervasive development disorders’, with a note for PDDs other than autism to be classed at 616.85883. This echoes the DSM-IV and ICD-10 (that is, a previous) approach to autism, which classed autism as one of five pervasive developmental disorders. The DSM-5 and ICD-11 moved to using the term ‘autism spectrum disorder’, encompassing a range of autistic traits and severities, including those previously categorised as Asperger’s syndrome. Asperger’s is classed at 616.858832, but as this term is no longer used, I imagine the call number will eventually fall out of use as well.

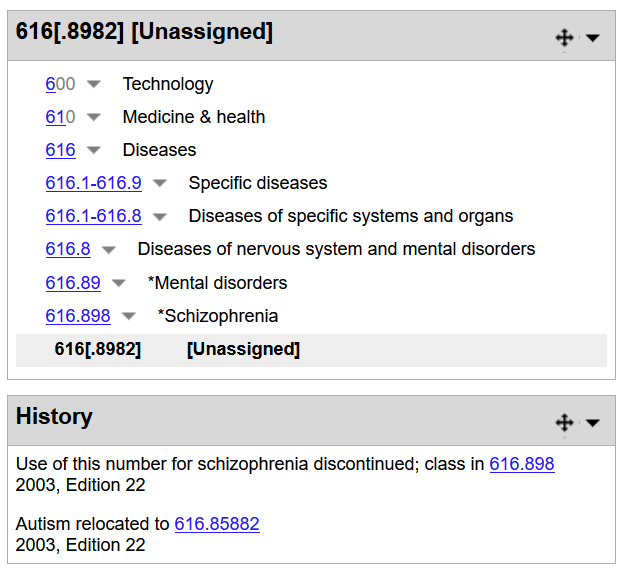

WebDewey notes that the class number for autism changed with DDC edition 22, published in 2003. Previously autism was classed at 616.8982, as… a subtype of schizophrenia. I gotta admit, this was news to me too. Autism was once considered a form of childhood schizophrenia; while WebDewey doesn’t tell me when a class number was first introduced, I’m guessing this dates from around the 1960s or 1970s. It could be worse, for sure, but it could be a lot better, too.

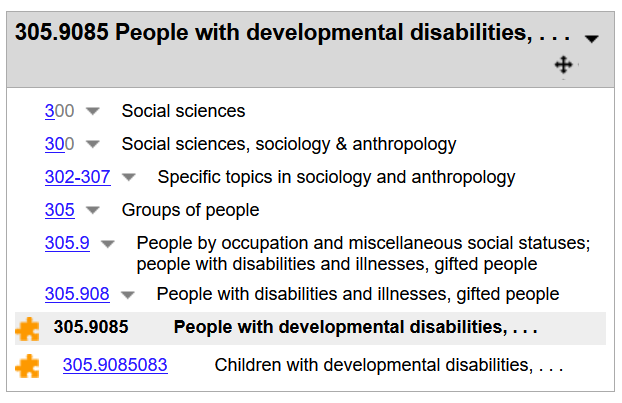

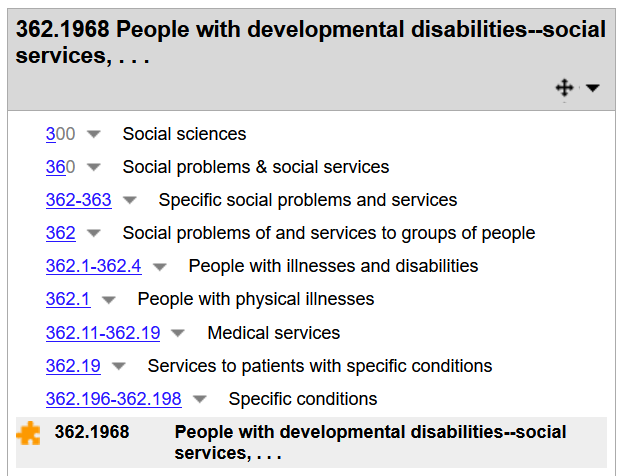

A class number for the social aspects of autism was harder to find. WebDewey returned no results in the 300s for the search term ‘autism’, but returned two strong suggestions for the search term ‘developmental disabilities’: 305.9085 for works on autistic people ourselves, and 362.1968 for social services to autistic people. The term ‘developmental disabilities’ doesn’t exactly reflect how I see myself, but I’m very aware these schedules were not designed with low-needs autistic people in mind.

Library of Congress (LCC)

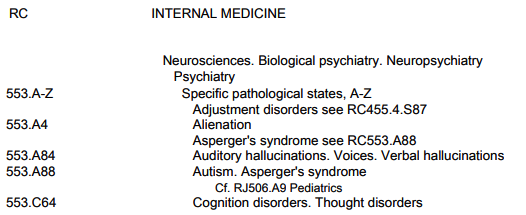

Until recently autism had only one LCC call number: RC553.A88, under ‘Internal medicine—Neurosciences. Biological psychiatry. Neuropsychiatry—Psychiatry—Specific pathological states, A-Z—Autism. Asperger’s syndrome’. I must admit, ‘specific pathological states’ is a more polite descriptor than I had expected to see in LCC—I don’t entirely hate it. Being a straight A to Z list it sits between ‘Auditory hallucinations’ and ‘Cognition disorders’.

Library of Congress cataloguer Netanel Ganin recently wrote about his efforts to address this absence, reinterpreting a call number range in the social sciences, HV1570, to include the social aspects of autism spectrum disorders. This accords with the treatment of other disabilities, such as blindness and deafness, whose medical aspects are classed in R and social aspects in HV.

Netanel notes that the full hierarchy of HV1570 (‘Social pathology. Social and public welfare. Criminology—Protection, assistance and relief—Special classes—People with disabilities—Developmentally disabled’) is not without its problems, as LCC can’t help pathologising autistic people as needing ‘protection, assistance and relief’ and most medical literature regards autistic people as being developmentally disabled, which also explains its preponderance in DDC. This class number is, however, an improvement on LCC medicalising the entirety of the autistic experience.

As an autistic cataloguer I applaud Netanel’s work in this area to help books find their most appropriate home in the LCC schedules, and to make the best of a bad system.

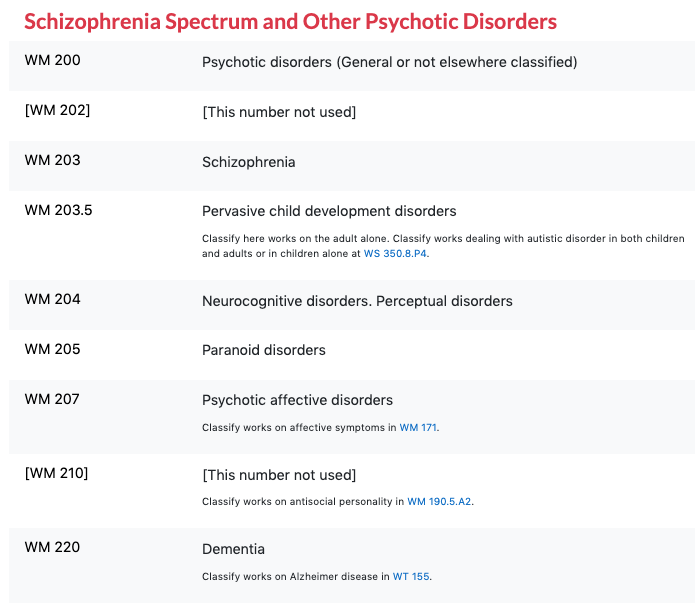

National Library of Medicine (NLM)

Sadly, NLM classification is the worst of the lot. Here, autism doesn’t even warrant listing under its own name, instead being lumped under ‘Pervasive child development disorders’ and classified with ‘Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders’, at WM 203.5. The number for autism sits between schizophrenia and neurocognitive and perceptual disorders.

In a rare act of classificatory transparency, NLM schedules are full of ‘[This number not used]’ where a call number has been removed and its subject classified elsewhere – unfortunately, between the Cutter number and the see reference text, one can often surmise which archaic or offensive words or concepts were previously listed.

Unlike DDC, NLM continues to encode the discredited view of autism as a form of childhood schizophrenia by choosing WM 203.5, instead of an unused number in the WM 200s. Yet as medical understandings of autism spectrum disorders have grown and improved, their classification here remains stuck in the 1950s. It’s also very strange that a call number relating to child development disorders, a diagnosis typically made in, you know, childhood, is specified for works relating to adults only.

Adding ‘spectrum’ to the broader category doesn’t change which individual disorders are collocated with each other. Nor does it change the overall message that sends. Am I supposed to be grateful that autism isn’t classed as a mental illness, or an intellectual disability? I would have expected NLM to be more in line with the classification decisions made by the DSM and ICD, but instead they’ve changed a dressing instead of closing an open wound. I hope they will reconsider this classification in future.