Yesterday I had the great privilege of attending the GO GLAM miniconf, held under the auspices of the Linux Australia conference. Hosted by the fabulous Bonnie Wildie and the indefatigable Hugh Rundle, GO GLAM brought the power and promise of open-source software to the GLAM sector. This miniconf has been run a couple of times before but this was my first visit. It was pretty damn good. I’m glad I started scribbling down notes, otherwise it would all be this massive blend of exhausted awesome.

The day began with an opening keynote by some guy called Cory Doctorow, but he wasn’t very interesting so I didn’t pay much attention. He did talk a lot about self-determination, and he did use the phrase ‘seizing the means of computation’ that I definitely want on a t-shirt, but there was a big ethics-of-care-sized gap at the centre of his keynote. I found myself wishing someone would use the words ‘self-determination’ and ‘social responsibility’ in the same talk.

Good tech platforms can exist, if we care enough to build them. As it happened, GO GLAM’s first speakers, a group of five mostly francophone and mostly Indigenous artists and coders from what is now eastern Canada, wound up doing almost exactly this. Natakanu, meaning ‘visit each other’ in the Innu language, is an ‘Indigenous-led, open source, peer to peer software project’, enabling First Nations communities to share art, data, files and stories without state surveillance, invasive tech platforms or an internet connection. I can’t express how brilliant this project is. I’m still so deeply awed and impressed by what this team have built.

Two things leapt out at me during this electrifying talk—that Natakanu is thoughtful, and that it is valuable. It consciously reflects First Nations knowledge cultures, echoing traditions of oral history, and exemplifying an ‘approach of de-colonized cyberspace’. Files are shared with ‘circles’, where everyone in a circle is assumed to be a trusted party, but each member of that circle can choose (or not) to share something further. Building a collective memory is made easier with Natakanu, but the responsibility of doing so continues to rest with those who use it.

Natakanu embodies—and makes space for—First Nations sovereignties, values and ethics of care. It’s technology by people, for people. It’s a precious thing, because our communities are precious, too. The Natakanu platform reflects what these communities care about. Western tech platforms care about other things, like shouting at the tops of your lungs to ten billion other people in an agora and algorithmically distorting individuals’ sense of reality. We implicitly accept these values by continuing to use these platforms. Our tech doesn’t care about us. We could build better tech, if we knew how, and we chose to. (There’s a reason I’ve been consciously trying to spend less time on Twitter and more time on Mastodon.) But more on computational literacy a little later.

A few people mentioned in the Q&A afterwards how they’d love to bring Natakanu to Indigenous Australian communities. I don’t doubt their intentions are good (and Hugh touched on this in the recap at the end of the day), but in my (white-ass) view the better thing is to empower communities here to build their own things that work for them. A key aspect of Reconciliation in this country is developing a sense of cultural humility, to recognise when your whitefella expertise might be valuable and to offer it, when to quietly get out of the way, and which decisions are actually yours to make. Or, as speaker Mauve Signweaver put it, ‘instead of telling them “tell us what you need and we’ll make it for you”, saying “Tell us what you need and we’ll help you make it”‘.

I can’t wait to rewatch this talk and catch up on some parts I know I missed. It was absolutely the highlight of the entire miniconf. I couldn’t believe they were first-time speakers! Can they do the keynote next year?

Metadata and systems might not last forever, but we can still try. I think it’s safe to say many attendees were very taken with Arkisto, the ‘open-source, standards-based framework for digital preservation’ presented by Mike Lynch. It’s a philosophical yet pragmatic solution to describing, packaging and contextualising research data. Arkisto’s framework appears particularly useful for rescuing and re-housing data from abandoned or obsolete platforms (such as an Omeka instance where the grant money has run out and the site is at risk of deletion).

Arkisto describes objects with RO-Crate (Research Object Crate, a derivative of Schema.org) and stores them in the Oxford Common File Layout, a filesystem that brings content and metadata together. It’s actively not a software platform and it’s not a replacement for traditional digipres activities like checksums. It’s a bit like applying the philosophy of static site generators to research data management; it’s a minimalist, long-term, sustainably-minded approach that manages data in line with the FAIR principles. It also recognises that researchers have short-term incentives not to adequately describe or contextualise their research data (no matter how much librarians exhort them to) and tries to make it easier for them.

The new PARADISEC catalogue includes Arkisto and an associated web interface, Oni, as part of its tech stack. I was very taken with the catalogue’s principle of ‘graceful degradation’—even if the search function ceases to operate, browsing and viewing items will still work. As a former web archivist I was heartened to see them holding this more limited functionality in mind, an astute recognition that all heritage, be it virtual, environmental or built, will eventually decay. So much of my web archiving work involved desperately patching dynamic websites into something that bore a passing resemblance to what they had once been. We might not always be able to save the infrastructure, but one hopes we can more often save the art, the data, the files, the stories. (Which reminds me, I’ve had Curated Decay on my to-read shelf for far too long.)

I shouldn’t have needed reminding of this, but sometimes I forget that metadata doesn’t begin and end with the library sector. It was a thrill to hear someone in a related field speaking my language! I wanna hang out with these people more often now.

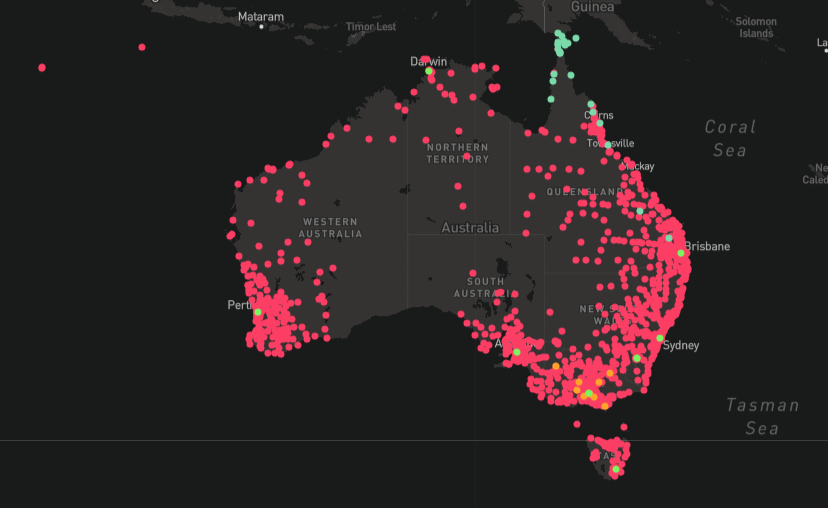

Generosity resides in all of us. My first impressions of Hugh Rundle’s talk were somewhat unfavourable—he only spent a couple of minutes talking about the bones of his project, a Library Map of every public library in Australia, and instead dedicated the bulk of his time to complaining about the poor quality of open datasets. Despite having had several sneak previews I was rather hoping to see more of the map itself, including its ‘white fragility mode’ and the prevalence of fine-free libraries across the country. Instead I felt a bit deflated by the persistent snark. Hugh was the only speaker to explicitly reference the miniconf’s fuller title of ‘Generous and Open GLAM’. But this felt like an ungenerous talk. Why did it bother me?

Perhaps it’s because Hugh is a close friend of mine, and I expected him to be as kind and generous about the failings of Data Vic as he is about my own. I’m not sure I held other speakers to that high a standard, but I don’t think anyone else was quite as mean about their data sources. I also hadn’t eaten a proper breakfast, so maybe I was just hangry, and I ought to give Hugh the benefit of the doubt. After all, he had a lot on his plate. I intend to rewatch this talk when the recordings come out, to see if I feel the same way about it on a full stomach. I hope I feel differently. The Library Map really is a great piece of software, and I don’t think Hugh quite did it justice.

Omg pull requests make sense now. Liz Stokes is absolutely delightful, and her talk ‘Once more, with feeling!’ was no exception. Her trademark cheerfulness, gentleness and generosity shone in this talk, where she explored what makes a comfortable learning environment for tech newbies, and demonstrated just such an environment by teaching us how GitHub pull requests worked. How did she know that I desperately needed to know this?! Pull requests had just never made sense to me—until that afternoon. You ‘fork’ a repository by copying it to your space, then make changes you think the original repo would benefit from, then leave a little note explaining what you did and ‘request’ that the original owner ‘pull’ your changes back into the repo. A pull request! Amazing! A spotlight shone upon my brain and angels trumpeted from the heavens. This made my whole day. Hark, the gift of knowledge!

Liz also touched on the value of learning how to ‘think computationally’, a skill I have come to deeply appreciate as I progress in my technical library career. I’ve attended multiple VALA Tech Camps (including as a presenter), I’ve done all sorts of workshops and webinars, I’ve tried learning to code umpteen times (and just the other day bought Julia Evans’ SQL zine Become a SELECT Star! because I think I’ll shortly need it for work), but nowhere did I ever formally learn the basics of computational thinking. Computers don’t think like humans do, and in order to tell computers what we want, we have to learn to speak their language. But so much learn-to-code instruction attempts to teach the language without the grammar.

I don’t have a computer science background—I have an undergraduate degree in classics, and am suddenly reminded of the innovative Traditional Grammar course that I took at ANU many years ago. Most students come to Classical Studies with little knowledge of grammar in any language; instead of throwing them headfirst into the intricacies of the ancient languages, they learn about the grammars of English, Latin and Ancient Greek first and together. This gives students a solid grounding of the mechanics of language, setting them up for success in future years. Programming languages need a course like Traditional Grammar. Just as classicists learn to think like Romans, prospective coders need to be explicitly taught how to think like computers. A kind of basic computational literacy course.

(Of all the things I thought I’d get out of the day, I didn’t expect a newfound admiration of Professor Elizabeth Minchin to be one of them.)

Online confs are awesome! Being somewhat late to the online conference party, GO GLAM was my first experience of an exclusively online conference. I’ve watched a handful of livestreams before, but it just isn’t the same. A bit like reading a photocopied book. I don’t think I had any particular expectations of LCA, but I figured I’ve sat in on enough zoom webinars, it’d be a bit like that, right? Wrong. The LCA audio-visual and conference tech stack was an absolute thing of beauty. Everything looked a million bucks, everything was simple and easy to use. It was a far more active watching experience than simply tucking into a livestream—the chat box on the right-hand side, plus the breakout Q&A areas, helped me feel as if I were truly part of the action. I didn’t usually have a lot to say past ‘That was awesome!’ but it was far less intimidating than raising my hand at an in-person Q&A or cold-tweeting a speaker after the fact.

As someone who is deeply introverted, probably neurodivergent and extremely online, virtual conferences like GO GLAM are so much more accessible than their real-life counterparts. I didn’t have to travel, get up early, put on my People Face™, spend hours in a bright and noisy conference hall, eat mediocre food, make painful small talk, take awkward pictures of slides and furiously live-tweet at the same time, massively exhaust myself and make a mad dash for the exit. Instead I could have a nap, grab another pot of tea, turn the lights down, share links in the chat, clap with emojis, watch people make great connections, take neat and tidy screenshots of slides, squeeze in a spot of Hammock Time and still be feeling excited by it all at the end of the day.

I’m sure people will want to return to some form of physical conferencing in the fullness of time, but I fervently hope that online conferencing becomes the new norm. This infrastructure exists, it costs a lot less than you think (certainly less than venue hire and catering), and it makes conferences accessible to people for whom the old normal just wasn’t working. Please don’t leave us behind when the world comes back.