Hello and welcome to Papercuts, an occasional series where I read some things and talk about how interesting they are. My friend Hugh launched a newsletter earlier today in a similar vein. You should read that too.

This series used to be called #emptythepocket but let’s be real here, I’m never going to empty this Pocket account. There are routinely over 1000 items in it, most of which I will probably never read. But I also can’t quite bring myself to delete them, or run pocket-snack. I went through it last night deleting some duplicates and manifestly uninteresting reads, in reverse chronological order, and I was fascinated by the stratigraphy of it all. Certain themes recur. Library ethics. Metadata. Ethnobotany. Radical politics. Mental health. Low technology. I could tell when I had reached January not by any timestamp, but by the profusion of smoke / bushfire / hailstorm / climate change / oh no we’re all doomed articles that I had saved, like a layer of igneous rock. They were probably quite cathartic for their authors to write but were too traumatic for me to read at the time, and I realised I would likely never read them at all. It’s a little odd reading my to-be-read pile as a text itself, as Hugh pointed out to me this morning. Imagine how much wiser I would be if I had actually read those things.

Part of the reason my Pocket account is so full is because when I’m unwell I can’t read anything. Words are just shells on a screen or a page. They have no meaning. I can’t make sense of them. Na’ama Carlin echoed this in ‘On the Name’ (Meanjin, Autumn 2019), about how names mean things, and how sometimes the names we give to things shape and constrain them. It’s strangely validating to read so many aspects of myself in someone else’s voice. The communality of shared experience, though Na’ama and I do not know each other, and our lives have undoubtedly been very different. She knows herself as ‘depressed’; she calls it by that name. I tend not to recognise myself as such until after the fog has cleared, at which point I look back at my crumpled form and go ‘wow, I was really depressed there’. My hope is that coming to know others’ narratives will help me understand my own.

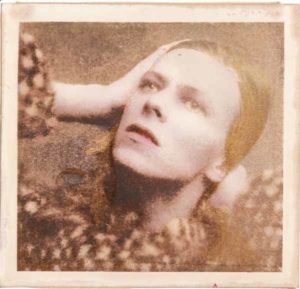

In that spirit, yesterday I listened to Honor Eastly’s mental health podcast No Feeling is Final (ABC Audio Studios, 2018) in its entirety, in one sitting (is it a ‘sitting’ if you’re lying in bed?). It was a raw and intense experience, using a lot of layering and metaphor and sound techniques to enable Honor to tell her story of what it’s like to ‘have big feelings’, to have a diagnosed name for those feelings, to be suicidal, in a psych ward, on meds, coping, not coping, sharing, creating a space for like-minded people, guiding others through the vast wasteland towards help and support. I related to many things and couldn’t relate to others, like any narrative of this kind. This podcast was A Lot, and I’m not usually a podcast person, so it was also a lot for my ears. But Honor is right. No feeling is final. There is always space for another one.

I had a birthday recently, as happens every year, and I received a deeply thoughtful gift: Around the World in 80 Trees, with text by Jonathan Drori and illustrations by Lucille Clerc (Laurence King Publishing, 2018). It’s essentially a collection of tree biographies, telling stories of how endemic trees around the world give shelter, materials, sanctuary and inspiration to communities that live around them. The narrative text is accompanied by beautiful illustrations of these trees, their fruits and flowers, and sometimes artefacts of the societies they support. I love this book because I can read it in chunks and/or a non-linear order, the Chinese white mulberry followed by the Dutch elm or the Californian redwood. Or, if reading is beyond me, I can simply look at the pictures, and learn just as much. It’s a beautiful book. I already treasure it.

I find great solace in nature. I spent part of my birthday trundling around Upper Ferntree Gully, admiring flowers, deciding I’m too unfit to ascend the 1000 Steps, buying lolly peach hearts by the kilo from the supermarket, and reading Tyson Yunkaporta’s Sand Talk (Text Publishing, 2019) under a tree. No I don’t know what kind of tree, yes I’m STILL reading this book! It’s a slow read. I’m a slow reader. I find I can also only read this particular book outside, which is quite interesting. The words lose their magic in a house or a train. They need that infusion of nature (or perhaps I do?) in order to make sense of the wisdom they convey. The book was composed as a yarn, a document of knowledge transmitted aloud, or etched as an aide-mémoire into the boomerang that features on the cover. A kind of metadata, perhaps, but bigger than that. I keep recommending this book to anyone who will listen but often I can’t quite explain what it’s about. Because it’s kind of about everything, but from an Indigenous perspective, in sharp contrast to the white one. I’m not sure what I’ll do with this wisdom once the book is over. I can’t keep it to myself. Maybe I can apply it somehow?

Developing a trees and plants hobby is one of the many ways I am slowly becoming my mother. She’s a hardcore gardener who can identify almost any plant whose photo I send to her. We see the world very differently, but I can’t help thinking she’d agree with the sentiment that ‘Life is Complicated and Mysterious and Dogmatism is Boring’, as expressed by Georgia Reid (The Planthunter, issue 68, 2019). For years mum carefully cultivated roses and shunned native plants, but our changing climate means she’s now planting some proteas and other things that are less thirsty. The article suggests it’s time to look more pragmatically at how plants might heal or improve our urban landscapes, whether they’re native to this continent, indigenous to this region, or introduced from overseas. A plant classed as a weed can actually improve lead-contaminated soils, while a non-native street tree still provides excellent shade cover. I find it a more helpful way of assessing how we live with plants, and might give my mother and I something to chat about when we meet next. Sorry mum, but I’ll never be an Essendon fan.