I got a lot out of a month’s holiday in Tasmania and in Melbourne, but perhaps the greatest gift was being able to read again. I don’t mean that I was previously illiterate, but rather that I no longer had the energy or interest in reading anything for longer than five minutes. I was (and still am) surrounded by books I longed to read, but knew I lacked the brainspace to absorb and make sense of them, and so I didn’t try.

Time away from work and the internet, and within nature, restored me to something like my former self. I realised I wanted to read again. I had forgotten what this felt like. My body had forgotten how to want to read books all day, and to be able to read books all day, and not have this gnawing pit of sad exhausted panic undercutting every paragraph. I hadn’t realised how profound a loss this was until I got it back.

I had packed four books for the trip:

- one I immediately lent to a friend (Track Changes by Matthew Kirschenbaum)

- one I didn’t get around to reading because I was too busy enjoying myself (Terra, volume 14 of the Dark Mountain Project)

- one I read to contextualise that enjoyment (Into the Heart of Tasmania by Rebe Taylor)

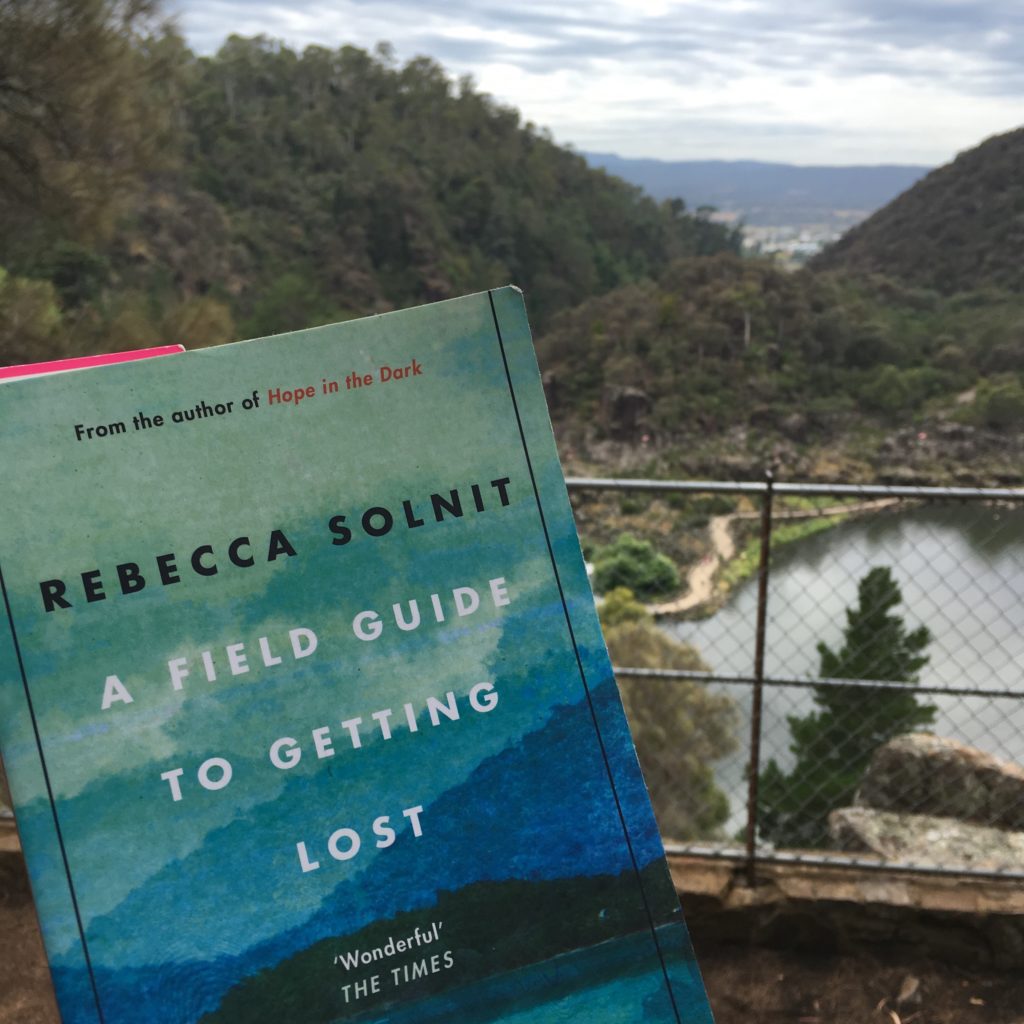

- and one I made a point of reading only in picturesque places (A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit). It’s an incredible book. I read it at Lake Wendouree, Ballarat; at Buckley Falls, Geelong; at Cataract Gorge, Launceston; at the blowhole in Bicheno. As it happened I read the last one and a half chapters of Field Guide on foot and on a tram, reaching the final line as I reached my final destination, bursting into the most hipster cafe in Fitzroy high as a kite on philosophy and the possible. Brunch was good that day.

Thankfully this spark has remained as I settle back into work and the internet. I still have loads of physical books to read, but I’m also finally making headway on my overstuffed Pocket account. Realising that it’s far easier to choose what to read when your selection is limited, my friend and comrade Hugh recently built an accidental serendipity machine called pocket-snack. It’s an experimental Python script for one’s pocket that presents you with a few randomly selected links per day, out of the several hundred you probably have saved (I had well over a thousand before we got the script to work). It’s helped me clear out stuff that it turns out I wasn’t actually interested in or that was no longer relevant to me, which freed up some brainspace for more worthwhile items. Emptying the pocket has truly never been so enjoyable.

Below are a few gems from the last little while, subconsciously themed around ‘the nature of information’:

Animism, Tree-consciousness, and the Religion of Life: Reflections on Richard Powers’ The Overstory / Bron Taylor, Humans and Nature

Full disclosure: I haven’t yet read The Overstory, the Booker-nominated 2018 novel whose central premise is that ‘entities in nature, and life itself, have agency, purpose, and personhood—and we have ethical obligations to all such persons.’ I’d had it in the back of my head to read at some point, noting that I seldom read fiction of any kind, and already have a to-read list as tall as I am. This review, however, propelled The Overstory to the top of my list.

I have a half-finished zine entitled ‘Five Epiphanies in Tasmania’. I’ve had a hard time pinning down the third, an experience in Ballroom Forest that I’ve likened to a moment of religious ecstasy. Reconciling this with my lifelong atheism has been somewhat challenging—whoever heard of an irreligious mystic? It seems my answer lies not in formal religious traditions, but in a kind of nature spirituality that recognises the consciousness of plants, natural features, and ultimately nature itself. Crucially, it also incorporates the responsibility of humankind to care for nature, while not situating ourselves above it. Review author Bron Taylor has dubbed this spirituality ‘dark green religion’, and his definition thereof is worth quoting at length:

It was within this complicated milieu that, over time, I began to notice patterns. These I eventually developed into the notion of dark green religion. This notion refers to diverse social phenomena in which people have animistic perceptions, emphasize ecological interdependence and mutual dependence, develop deep feelings of belonging and connection to nature, and understand the biosphere as a sacred, Gaia-like superorganism. These sorts of nature-based spiritualities generally cohere with and draw on evolutionary and ecological understandings and therefore stress continuity and kinship among all organisms. Uniting these Gaian and animistic perceptions is generally a deep sense of humility about the human place in the universe and suspicions of anthropocentric conceits, wherein human beings consider themselves to be superior to other living things and the only ones whose interests are morally significant.

To learn that this worldview not only had a name, but was a Thing that others felt and lived and wrote novels about, was overwhelming. I was slightly late to work from reading this article. I regret nothing.

If the map becomes the territory then we will be lost / Mita Williams, Librarian of Things

This sounds like a geography article but it’s not—Mita Williams, a scholarly communication librarian based in Canada, writes on how social graphs and scholcomm ecosystems are beginning to shape, rather than merely guide access to, academic output. The big 3 companies (Clarivate, Elsevier and Springer-Nature) are integrating their component services more and more tightly, which has the effect of widely automating—and locking humans, especially librarians, out of—the scholarly publishing process. Mita also discusses a higher education funding mechanism in Ontario that sounds a bit like the UK’s REF (Research Excellence Framework), in that it determines how much money is allocated to various institutions on the basis of some highly exclusionary and frustrating metrics.

Their models are no longer models. The search engine is no longer a model of human knowledge, it is human knowledge. What began as a mapping of human meaning now defines human meaning, and has begun to control, rather than simply catalog or index, human thought. No one is at the controls.

I won’t pretend to be anything near an expert on scholcomm but this all sounds fairly… rubbish. No wonder people want to dump Elsevier.

Computational Landscape Architecture / Geoff Manaugh, BLDGBLOG

I love trees. I also love wifi. But the two are strange bedfellows. This article explores the impact different species of tree might have on phone and internet reception, leading to ‘the possibility that we might someday begin landscaping […] according to which species of vegetation are less likely to block WiFi’ and the potential use of pot plants in electronic subterfuge. I mean, Geoff also links to an article from Popular Science suggesting wifi is responsible for mass radiation poisoning in Dutch street trees, so I’m not entirely convinced wifiscaping is a good idea, but it’s yet another reminder that computing, like the rest of human ingenuity, exists within nature and not above it.

PROSPEKT. Organising information is never innocent / Regine, We Make Money Not Art

I initially read this before going on holidays, but VR performance artist Geraldine Juárez has some incisive comments for the GLAM sector that I thought deserve a wider audience. The bulk of this article discusses PROSPEKT, her 2018 performance situated within the Gothenburg Botanical Garden, Sweden. The first paragraph, however, is a neat summary of her 2017 essay ‘Intercolonial Technogalactic’ [large PDF, begins page 152]. In it, Juárez critiques the activities of the Google Cultural Institute, which has digitised and published online thousands of museum-held cultural artefacts from around the world, but which curiously offers very little information about its own origins. (It was intended as part of a PR move against French publishers who were suing Google in 2011 over Google Books and breaches of copyright.)

She notes that Google views libraries, museums and other cultural institutions not as true collaborative partners but as ‘gatekeepers of world cultures’: repositories of content to be mined and paywalled. Google reproduces the power structures and cultural biases that gave rise to it, prizing European high culture above all else, and viewing publicly-funded institutions as beacons of ‘inefficiency’ that need ‘disrupting’ by private enterprise. All information is organised for a purpose. It is never innocent. It is never neutral.

The colonial gaze was determined to scan the surface looking for specimens for study, fixing them as objects out of time and out of place, in the same way that digital documents offer imagings of the world at a distance via screens. This is a prospecting gaze – a wandering ogle that examines, sorts and determines meaning and value.

While re-reading this article I was violently reminded of a series of uncomfortable experiences at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart. I’ve never been wild about taxidermy, but TMAG’s hall of lovingly stuffed creatures, with mammals, birds and insects wrenched from their natural homes and drowned in formaldehyde, made me deeply uncomfortable. These poor animals deserve to return to the earth, not spend the next three eternities in suspended animation for the amusement of humans.

Natural Processes: information doesn’t grow on trees / Ana Cecilia Alvarez, Real Life

This piece has had such an impact on how I think about cataloguing that I’m including it again. It reminded me that the very notion of cataloguing and classification has deeply imperialist foundations that bode ill for our efforts at more inclusive collection description. It also reminded me of how my dear mother, a keen gardener, was able to identify every plant photo I texted to her during my trip. Sometimes it’s far better to ask mum than ask Google. Or an app reliant on crowdsourcing and machine learning.

The “herborizer,” a 17th-century nature enthusiast “armed with nothing more than a collector’s bag, a notebook, and some specimen bottles, desiring nothing more than a few peaceful hours alone with the bugs and flowers,” was the passive cousin of the conquistador or the diplomat […] His harmless assertion of taxonomical hegemony over Europe and her colonies actually produced commercially exploitable knowledge for the empire’s gain. He was a researcher, classifying, collecting, qualifying and quantifying imperial loot.

By cataloguing nature in ways that privileged only select facets of a living thing (those that could be seen, felt, or observed in isolation from its natural habitat), the burgeoning fields of taxonomy and scientific classification enabled Enlightenment-era Europeans to distance themselves from the natural world they ravaged. It continues to enable users of the aforementioned plant-identifying app, which propagates this classificatory, imperialist method of coming to know the earth. Taxonomy, with its discrete categories and precise hierarchies, primes us to see nature as a resource, as something to be mined, prospected and extracted for humanity’s benefit (such as improving our wifi). ‘It teaches us to see other life as proximate to us, rather than knowing ourselves as an extension of it.’

The antithesis of Bron Taylor’s dark green religion. The very anthropocentrism to which Richard Powers’ The Overstory stands opposed.

I titled this blog Cataloguing the Universe because it reflected a childhood impulse to never stop learning about the world, about space and time, about my place on this planet. Library catalogues have always been, for me, a path to knowledge: first as I browsed them, now as I contribute to their upkeep. It’s only within the last couple of years that I’ve learned how taxonomies and classification systems reflect the views, biases and priorities of those who create them. It’s only within the last hour that I’ve realised the binary character of natural history classification is echoed within my work as a cataloguer. I can assign a book only one call number. I can either include or not include a subject heading—no parts, shades or relevance rankings, no way to indicate just how well a work relates to the subjects I decide it’s about. It’s not a good system. How can I smash it?

This notion of cataloguing as a means of collecting and producing knowledge, like everything else about the culture I was raised in, is inherently Eurocentric and deeply flawed. I couldn’t quite articulate this in late January, but I can now. This is why I wanted to learn differently this year. To overcome my ecological illiteracy borne from spending 28 years inside on someone else’s land. To learn different ways of seeing the world, so that I might address the harm my settler presence has caused.

The article’s conclusion suggests the first step is ‘to take off our lenses and reckon with the humbling, bewildering condition of unknowing, to [quell] the appetite for legibility of the world that leaves us at a comfortable distance from what we cannot understand.’ I don’t think I’m comfortable enough yet with my own ignorance. I have so much to unlearn.