I am tired.

Most days I get enough sleep, eat a reasonable breakfast, get to work on time, look and feel on the surface like I’m awake, but it’s only a shell. It’s been a tough year. I’ve started a new job, I’ve been sick a lot, and I still can’t stop saying ‘yes’ to things.

When I’m in the right headspace, everything is doable, and I proudly tell people that I’d love to get things done for them. But when I’m in the wrong headspace, everything feels insurmountable, and I don’t want to tell people that because it makes me look like a fraud. I have little to no control over what headspace I wake up in on any given day. I can’t tell you how frustrating this is.

I have a lot on my plate at the moment. Most of it is library-related. I love what I do, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I can’t talk about everything I’ve volunteered my time for, but I’m on a few LIS committees, I have three (!) conference / PD event presentations scheduled in the first half of next year, I do a lot of cataloguing reading and research, and I participate in a couple of miscellaneous LIS projects. I say this not to boast, nor to complain, but rather as an illustration of what happens when I say ‘yes’ to everything, because I’m still a little stunned that people ask me to do anything at all.

The problem is that whenever I look at my never-ending to-do list, my short-circuiting brain misinterprets ‘these are things you need to do’ as ‘these are things you need to do RIGHT NOW’. Consequently I panic a lot about how much I haven’t done. The problem is, as usual, a lack of temporal perspective. Some of the things aren’t due for another six months. They can wait. Other things are due last week, so they need more urgent attention.

me: I have so many things I want to do and so much on my plate and an endless stream of ideas, goals and projects

also me: I spend one day every weekend in bed because I’m too exhausted to get up

— Alissa M. (@lissertations) 16 November 2018

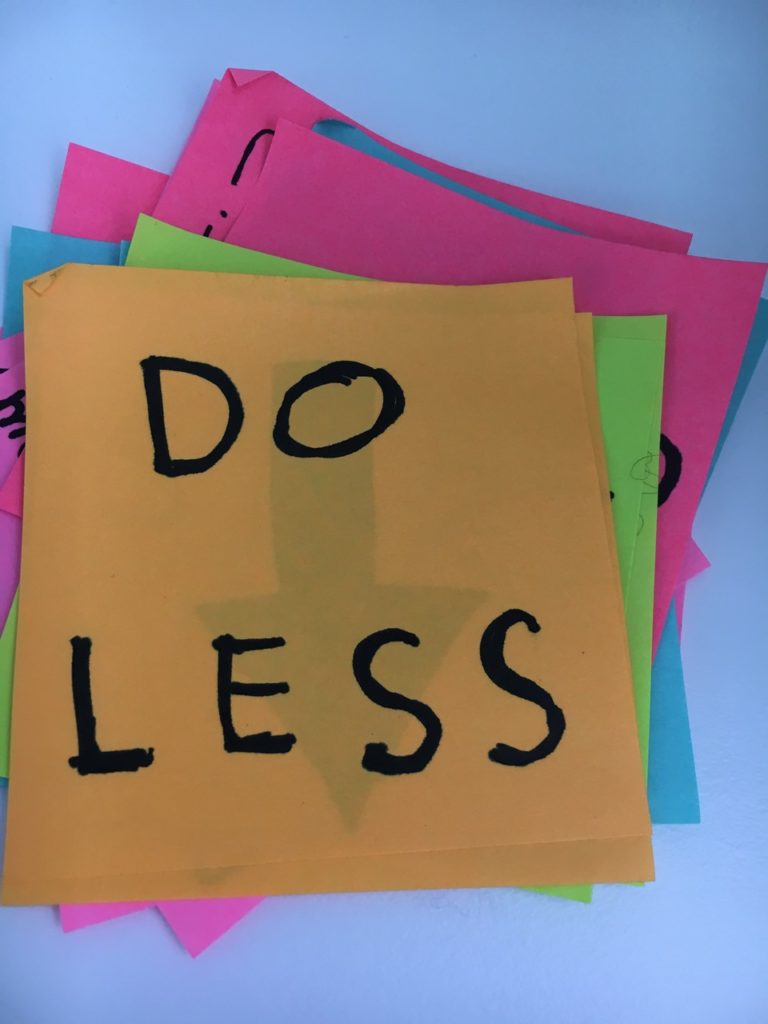

the obvious solution is to say yes to less, and I’m working on other less obvious solutions, but I wonder at what point my stamina stopped keeping up with my enthusiasm

— Alissa M. (@lissertations) 16 November 2018

Did I mention how much I love what I do? I mean this sincerely. I can’t think of anything else I’d rather be doing with my life. But I’m beginning to reach some hard limits on how much I can achieve as an individual. I resent these limits (because who doesn’t want to do all the things?!) while recognising that they are necessary (because we can’t do any of the things if we’re completely exhausted).

Shira Peltzman shared this wonderful flowchart with me, outlining how she decides whether to say yes or no to a professional opportunity. I’ve found it really helpful in evaluating all the things I’ve recently said ‘yes’ to, and whether I should perhaps have made other decisions. The flowchart is also Creative Commons-licensed so you can print it out and stick it next to your desk. Note that most of the arrows point to saying ‘no’. I think I’ll be referring to this flowchart a lot.

There’s a great Mastodon bot called Wollstonecraft BOM, a weather bot for a Sydney suburb I have never been to. Every few hours it spits out some weather data and a forecast, but it also includes a lovely little platitude at the end as a mood-booster, and I follow the account purely for this reason. While I was drafting this post a week ago it said to me, ‘You’re doing the best you can, and good people know it.’ I try to remind myself of this a lot, that I am doing the best I can, even if some days that best is not very good.

Part of me wanted to spike this blog post, that being tired isn’t a good look, professionally. But I want to talk about this stuff. It’s important that we aren’t all hiding behind veneers of perfection, telling the world we have it together while over-caffeinating ourselves into oblivion1, because not talking about being tired is part of how we all became tired in the first place. By admitting our exhaustion, we recognise that things aren’t quite right, and we begin the difficult process of balancing ourselves.

Recently I was made an offer. Quite a good offer. And my response, after considerable thought, was ‘Yes… but’. I never used to ask for concessions or amendments, and I’m not a natural negotiator, but reaching hard limits necessarily entails making sure I don’t exceed them. I’m a little impressed with myself, and very grateful that the offerer was prepared to accommodate me.

I’m still tired, but now I’m looking forward to next year because of all the things I’ve said ‘yes’ to, not in spite of them. I hope this means I’ll find myself in better headspaces, where more good things can happen. 🙂

- I was recently forced to give up caffeine cold-turkey for medical reasons. I miss Lady Grey tea really quite a lot, but I think not being able to push myself beyond my natural limits has actually helped me recalibrate. This is a personal view. Your mileage may vary. ↩