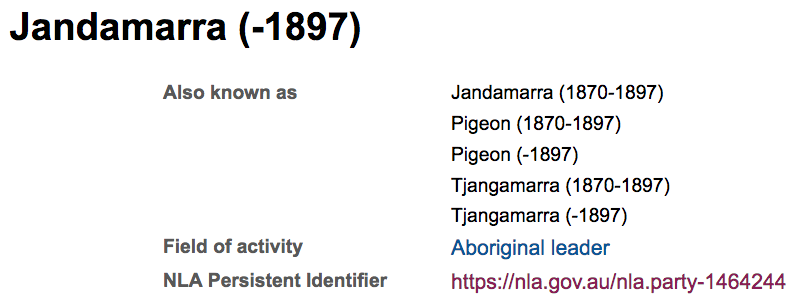

UPDATE (20 June 2018): This has now been addressed! I noticed a couple of days ago that the NLA have updated this authority record, such that it now follows the AIATSIS example, “Jandamarra, approximately 1870-1897.” (The Libraries Australia heading and Trove duplicate issue both remain, but I understand they are managed by different areas within NLA.) While I was not directly informed of the NLA’s decision to update Jandamarra’s authority record, I am thrilled that they have done so. Thank you, NLA cataloguers, for making this necessary change.

It’s all well and good for librarians to talk about decolonisation, but we need to put our money where our mouths are. Cataloguers are no exception—we decide how resources are described and accessed. We dictate the effectiveness of a search strategy. We alone have the power to name.1

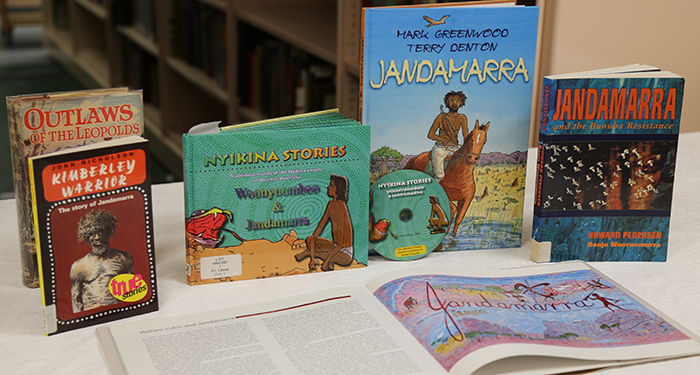

Being the sort of person who browses library catalogues for fun, I wound up on a NLA record for a play about Jandamarra, the Bunuba resistance fighter. Except the subject headings in this record didn’t name him at all. Instead they named some bloke called ‘Pigeon’.

100 0# $a Pigeon, $d -1897 400 #0 $a Jandamarra

Pigeon?!

Apparently ‘Pigeon’ was a name given to Jandamarra by a white pastoralist.2 The 15 books held by the NLA with this subject heading overwhelmingly refer to a man named Jandamarra. His entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography is under this name. The Canberra street named in his honour uses this name. Why doesn’t the NLA use this name?

The whole thing couldn’t be more colonial if it tried.3 A colonial institution (the library) referring to an Indigenous man by a colonial name (‘Pigeon’) and qualifying it with his year of death in a colonial calendar (1897). Jandamarra’s authority record represents his name and life as it was known to white people. How would the Bunuba describe him? Would they use the name ‘Jandamarra’ at all? What could a more culturally appropriate authority record look like? How might we disambiguate people without reference to colonial names, occupations or calendars?4

100 0# $a Jandamarra $c (Bunuba man) 400 #0 $a Pigeon, $d -1897

As a white cataloguer I firmly believe a change needs to be made. Such a change would have greater impact if it were also made in Libraries Australia, the national union catalogue (on which more later). The name ‘Pigeon’ is also used there, identically to its use in the NLA’s catalogue.

Let’s fix that

The issue then becomes: how might I make this change? More importantly, how might the community suggest a change? There is a way to suggest changes to name headings on the ANBD, but it’s very difficult to find—the Libraries Australia reftracker includes two options for ‘Propose a LCSH change’ and ‘Propose a new LCSH’ (where ‘LCSH’, apparently, includes all headings, name and subject alike). The form states that the info you provide goes straight to LC (that is, it’s not evaluated locally). It also immediately starts demanding my name, my NUC code, tells me to choose my 1XX heading, include 670 source citations, LC pattern or SCM memo, use for, broader term, related term??

I am a fluent MARC speaker and I know a 680 when I see one, but I have never dared fill out that form. I can’t see how an ordinary person would ever be able to suggest a formal change for Australian usage. Crowdsourcing initiatives like Violet Fox’s Cataloging Lab (which, for the record, I love), are necessarily US-centric and wouldn’t immediately address a local problem. Besides, the guidelines for establishing name authorities in the ANBD expressly state that Australian entities are exempt from the ‘let LC decide’ policy.

Besides, even if we were able to navigate the form and suggest a change, what would the change be? For guidance, I looked to AIATSIS’ catalogue. Sensibly, and in delightful accordance with RDA, they have opted to use 100 0# $a Jandamarra, $d approximately 1870-1897 as the preferred form. I figure if it’s good enough for AIATSIS, it’s good enough for me.

Wondering what other libraries used, I then looked at the Library of Congress’ NAF (Name Authority File) record. To my surprise, they used a different spelling:

100 0# $a Sandamarra, $d -1897 400 #0 $a Jandamarra, $d -1897 400 #0 $a Pigeon, $d -1897 400 #0 $a Tjandamara, $d -1897

This record was created in 1989 and revised in 2013. A search of both LC’s catalogue and WorldCat (via the Libraries Australia Z39.50 interface, in case that makes a difference) brought up no results with this spelling, so I couldn’t determine if a particular work was used as its basis. Usually these works would be recorded in a 670 field, but these had nothing.

It would not be beyond LC to update its heading to the more commonly-used spelling. Pleasingly, they have form in this area: in 2003, LC changed several dozen subject headings relating to $a Aboriginal Australians (or $a Australian aborigines, as they were then described) in consultation with the NLA.

What’s in Trove?

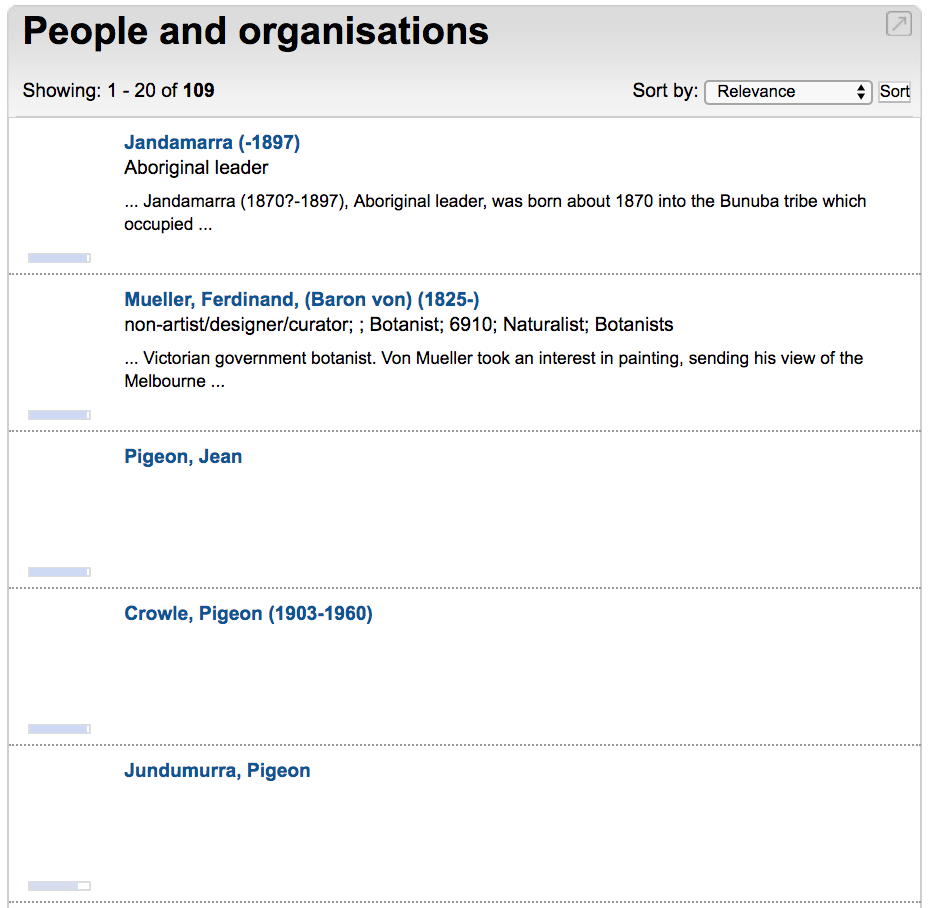

I then found myself browsing the Trove People and organisations zone, where authority records are given a new life as sources of biographical data. Like other parts of Trove, the P&O zone aggregates and incorporates data from a variety of sources. I was therefore surprised to find Jandamarra listed under this name, using data from AIATSIS and the Australian Dictionary of Biography; as established above, both sources used the most commonly-known spelling. Notably, this did not include data from Libraries Australia:

The great thing about Trove identity records is that they display the ‘Also known as’ data (or UFs, or non-preferred terms, or 4XX fields, or whatever). It’s really hard to get an ILS to display this info, especially in an easy-to-read format like Trove has done. I’m really pleased to see this data out in the open and not hidden down the back of the authority file sofa.

Now, what happens if I search the P&O zone for ‘Pigeon’?

We see that Jandamarra (-1897) is the first result, but the fifth is for Jundumurra, Pigeon (?!), which features data from AIATSIS and Libraries Australia. (This particular LA record pulls its data from AIATSIS anyway, so strictly speaking this isn’t the NLA’s fault, but it’s still a dupe that LA and/or Trove would have to merge.)

Interestingly, the original authority record from the NLA (‘Pigeon’, remember him?) doesn’t appear to be represented in the P&I zone at all. I wonder if that was a conscious or unconscious decision?

For completeness, here’s the real AIATSIS name authority, which in my view is also the best one:

100 0# $a Jandamarra, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Jundamurra, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Sandamara, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Sandawara, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Tjandamara, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Tjangamarra, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Jandamura, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Pigeon, $d approximately 1870-1897 400 #0 $a Wonimarra, $d approximately 1870-1897

It turns out that Jandamarra has three (!) name authority records in Libraries Australia, one from the NLA and two from AIATSIS. Ordinarily I would consider this a major data integrity issue, and 100 10 $a Jundumurra, Pigeon is a bit of a problem, but for the moment I’m actually okay with the other two full-level records, because they help illustrate the differing approaches and mindsets from the two institutions. In time, I’d like to narrow that down, though.

Recommendations

In short, here’s what I would like to see happen so that Jandamarra is referred to by his rightful name in the ANBD, and in catalogues that use ANBD records:

1) Libraries Australia to modify their name authority record and establish the preferred form as $a Jandamarra, $d approximately 1870-1897, in accordance with that used by AIATSIS, and add non-preferred forms as appropriate. This change could then ripple across to the NLA’s catalogue, and other libraries that use Libraries Australia authorities would eventually follow suit. Maybe a little publicity around the change—after all, it’s being done for the right reasons.

2) Trove to merge the two identity records such that Jandamarra appears only once, that ‘Pigeon’ appears under the ‘Also known as’ list (so those who know him by that name are redirected accordingly), and that the sources of data encompass AIATSIS, Libraries Australia and the National Dictionary of Biography.

Such moves may seem small, but they would represent a sincere and concerted effort to decolonise the authority file. Cataloguers can, and should, restore the power to name to Indigenous communities, especially where colonial names have been used to describe Indigenous people and concepts. A name is not the cataloguer’s to take—it is the community’s to give.

- Olson, Hope A. (2001). The Power to Name: Representation in Library Catalogs. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 26(3), 639-668. doi: 10.1086/495624 ↩

- Pedersen, Howard (1990). Jandamarra (1870–1897), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/jandamarra-8822/text15475 Accessed 20 May 2018. ↩

- For more on the cultural sensitivities around Indigenous subject headings, see Kam, D. V. (2007). Subject Headings for Aboriginals: The Power of Naming. Art Documentation: Bulletin of the Art Libraries Society Of North America, 26(2), 18-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/adx.26.2.27949465 ↩

- See also Frank Exner, Little Bear’s excellent treatise on Native American names in the world’s authority files: Exner, Frank, Little Bear (2008). North American Indian Personal Names in National Bibliographies. In Radical Cataloging: Essays from the Front. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co. ↩