6. There is no business as usual in a #ClimateEmergency. We urgently need government to develop a national resilience framework to look after our people and our country as the climate damage worsens. This needs to cover every community and every sector.

— David Ritter (@David_Ritter) December 9, 2019

All around me, people act like it’s business as usual. My city is shrouded in smoke. So many people around our region keeping fires at bay. I keep waking up with a crackling throat and a tightness in my chest. And yet the library is all Christmas and the news is all Pravda. I wonder sometimes what planet I’m on.

‘Resilience’ and I are strange bedfellows. On one hand, I am acutely aware of the sheer neoliberal hubris involved in pushing resilience mantras onto people facing structural harm, inter-generational trauma, or planetary apocalypse, as if an inability to cope with those things is simply a personal failing. Coping is a bandaid. Coping doesn’t fix the cause. Coping won’t make it stop.

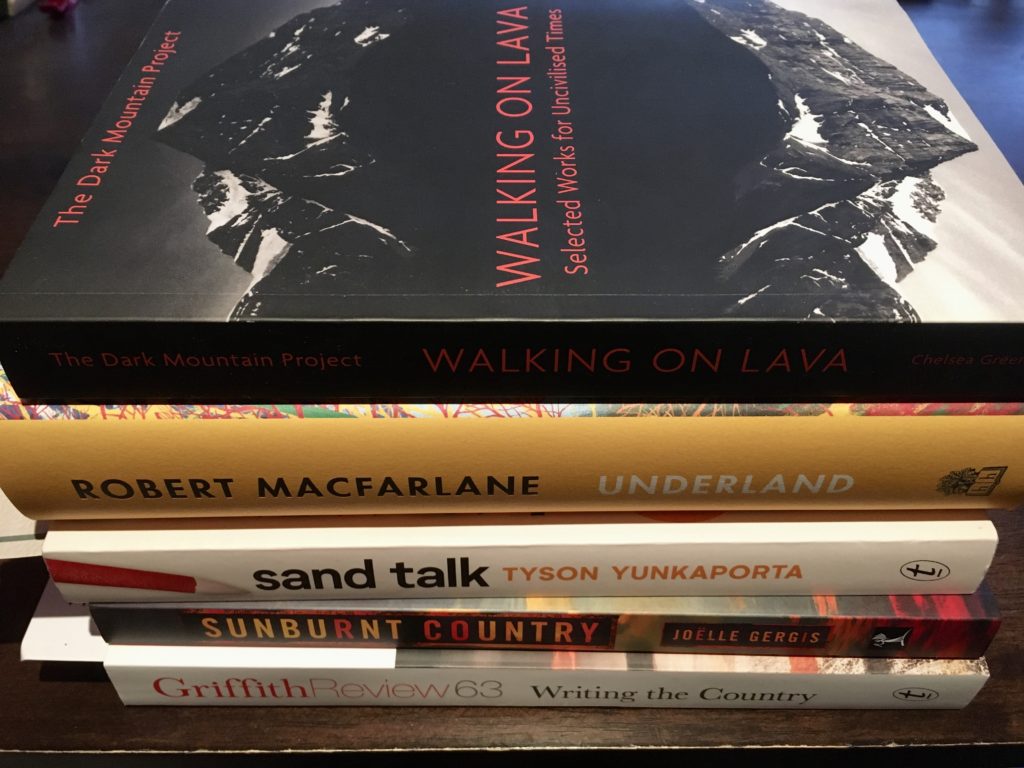

But at the same time: we can’t build futures we can’t imagine. Many people turn to fiction for inspiration and guidance, particularly speculative fiction and various futurism genres. I’m not much of a fiction reader1, so instead I turn to works of natural history and new nature writing, to know what has come before us, and what might be next. Truth hurts. And yet it comforts me.

If we yield to panic, we lose that ability to see into the distance, even as that distance is shrouded in ash.

From here, the future looks grim. Despite the desperate need for whole-scale systematic change, I have no faith that those with the power to enact such change will do so. We cannot wait for promised technologies, promised public policy, or a promised saviour to rescue us from this mess. We may not even be able to rescue ourselves. But trying is the only option available to us. And we must try together.

This is essentially the plot of Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark, a book I’ve turned to a few times this year, and which I should probably purchase instead of hoarding a friend’s copy. I find myself taking a chapter as medicine when it all seems particularly awful. Most things are terrible. But not everything. And in the space between there is room to act.

Because my eyesight is dreadful I own three pairs of glasses, yet I see most things through a library lens. It’s tempting to imagine the library as a microcosm of its broader society: a magical place where we might build better social relations or knowledge arrangements. But the longer I spend in librarianship, the more I see our structural problems replicated beyond the microcosm. We can’t solve them in isolation.

Most of the problems with librarianship that we want to solve are bigger than the industry or profession itself.

— hugh (@HughRundle) December 8, 2019

I look outside, I read the news, I hear the anguish of those all around me, I think about what I’m not hearing, and I wonder… why am I even at work? Is it because the air is nicer inside? Is it so I can delude myself that what I do here will matter in the long term? Is it even mattering now? Is it all just so much busywork while we wait for the world to end?

I’m a web archivist. I’m also an environmentalist. I’m probably a hypocrite.

The internet doesn’t exist in the ether… it exists in server farms. In triplicate or more. That use massive amounts of carbon to construct, outfit, and run. Digital isn’t low impact, it’s actually quite high impact. https://t.co/xBo2eYEOmw

— Krista Jamieson (@ArchiveThoughts) December 9, 2019

We also shouldn’t try to save everything as long as the internet is fossil fueled (which it mostly is). Your WARCs and AIPs/DIPs/SIPs and disk images have their own carbon footprints. https://t.co/7Ac9QXMlGQ

— ProjectARCC (@projectARCC) December 9, 2019

In addition to being hugely carbon-intensive (irrespective of whether or not it’s powered by renewable energy), global computing consumes huge amounts of natural resources, including oil and rare-earth minerals, and produces colossal amounts of waste. Supposedly ‘green’ technology is costing the earth. Absolutely everything about web archiving is unsustainable. I wonder if it could ever become sustainable. I don’t like our chances.

I say this as someone whose job relies on these same technologies + infrastructures. I’m as complicit as anyone.

But instead of asking ‘how can we make [thing] better for the planet’ we must instead ask ‘should [thing] continue at all’—and be prepared for the answer to be ‘no’.

— Alissa M. (@lissertations) September 18, 2019

So what do we do next? I know I ended my last blog post with ‘I don’t have the answers’, and despite the professional vexation of remaining answerless, here I am still searching. I’m not a climate scientist or a political ecologist or someone with decades of direct and relevant life experience. Instead here I am, adrift in a sea of reckons.

The easterly smokewind—the muril bulyaŋgaŋ, as the Ngunnawal might call it—forms a kind of hideous poetry. Where it used to bring cool relief of an evening, the easterly now carries smoke from fires between us and the ocean. I dread the breeze, now. It’s all wrong. It’s not normal. I resent what the climate is doing to us. I grieve for what we have done to the climate.

We all have to face ourselves in the mirror. I wonder who I want to see, what kind of person I hope to become, forged as we all are by our hideous circumstances. What would I see in the mirror of Erised? A perfect catalogue? A temperate forest? A group of friends? Or would I be grateful to see anything beyond a shimmering void?

I am sad, weary, listless, lonely, tired. I see few lights on the horizon, and I’m meant to be one of the lucky ones. I often think about giving up. And then I take stock, and I dream. I dream of building strong, resourceful, resilient communities. I dream of rewilding barren landscapes, following Indigenous caretakers in restoring biodiversity and ecological health. I dream of being able to open my windows in the evening and not be ambushed by smoke haze. I dream of solidarity with each other and the land. I dream of finding answers. I dream of doing the impossible. I dream of not doing this alone.

We are indeed through the looking-glass. But it needn’t be a one-way trip.

- This was the primary reason why I opted out of ALIA SNGG’s book secret santa this year. I have very niche reading tastes, am extremely hard to buy for, and also suck at readers’ advisory. 🙃 ↩