I’m not attending ALIA Information Online this year, largely because the program was broadly similar to NDFNZ (which I attended last year) and I couldn’t justify the time off work. Instead I’m trying to tune into #online17 on Twitter, in between dealing with mountains of work and various personal crises.

As usual, there’s a lot of talk about linked data. Pithy pronouncements on linked data. Snazzy slides on linked data. Trumpeting tweets about linked data.

You know what?

I’m sick of hearing about linked data. I’m sick of talking about linked data. I’m fed up to the back teeth with linked data plans, proposals, theories, suggestions, exhortations, the lot. I’ve had it. I’ve had enough.

What will it take to make linked data actually happen?

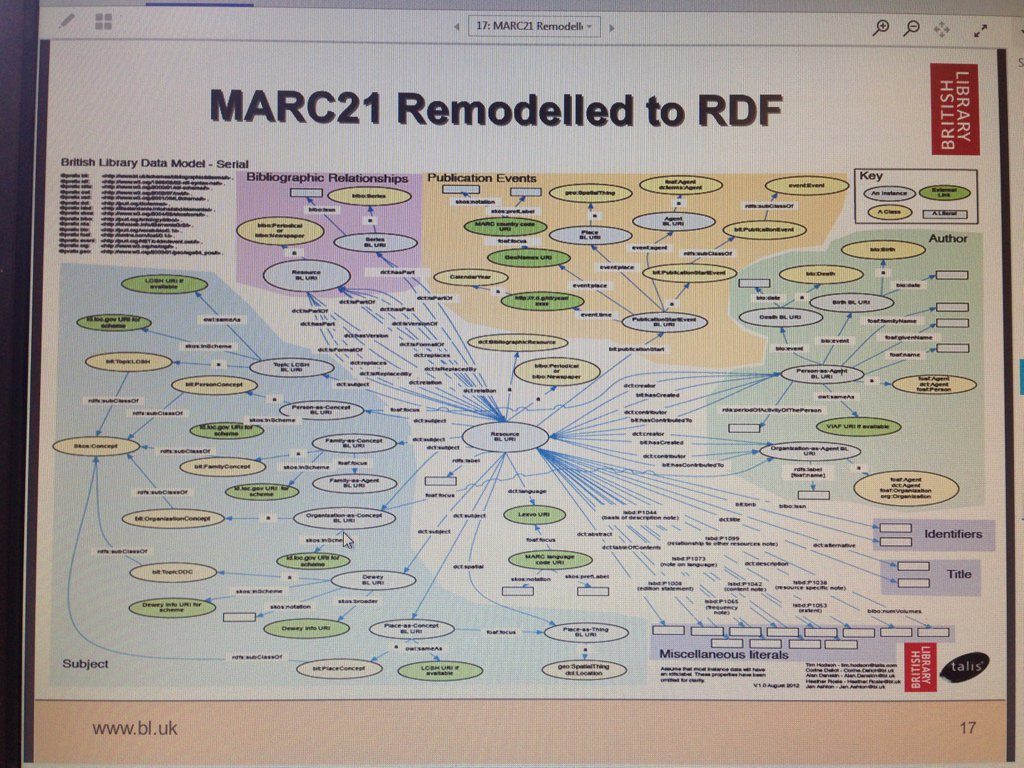

Well, for one thing, ‘linked data’ could mean all sorts of things. Bibframe, that much-vaunted replacement for everyone’s favourite 1960s data structure MARC, is surely years away. RDF and its query language SPARQL are here right now, but the learning curve is steep and its interoperability with legacy library data and systems is difficult. Whatever OCLC is working on has the potential to monopolise and commercialise the entire project. If people use ‘linked data’ to mean ‘indexed by Google’, well, there’s already a term for that. It’s called SEO, or ‘search engine optimisation’, and marketing types are quite good at it. (I have written on this topic before, for those interested.)

Furthermore, linked data is impossible to implement on an individual level. Making linked data happen in a given library service, including—

- modifying one’s ILS to play nicely with linked data

- training your cataloguing and metadata staff (should you have any) on writing linked data

- ensuring your vendors are willing to provide linked data

- teaching your floor staff about interpreting linked data

- convincing your bureaucracy to pay for linked data and

- educating the public on what the hell linked data is

—requires the involvement of dozens of people and is far above my pay grade. Most of those people can be relied upon to care very little, or not at all, about metadata of any kind. Without rigorous description and metadata standards, not to mention work on vocabularies and authority control, our linked data won’t be worth a square inch of screen real estate. The renewed focus on library customer service relies on staff knowing what materials and services their library offers. This is impossible without good metadata, which in turn is impossible without good staff. I can’t do it alone, and I shouldn’t have to.

Here, the library data ecosystem is so tightly wrapped around the MARC structure that I don’t know if any one entity will ever break free. Libraries demand MARC records because their software requires it. Their software requires MARC records because vendors wrote it that way. Vendors wrote the software that way because libraries demand it. It’s a vicious cycle, and one that vendors currently have little incentive to break.

I was overjoyed to hear recently of the Oslo Public Library’s decision a few years ago to ditch MARC completely and catalogue in RDF using the Koha open-source ILS. They decided there was no virtue in waiting for a standard that may never come, and decided to Make Linked Data Happen on their own. The level of resultant original cataloguing is quite high, but tools like MARC2RDF might ameliorate that to an extent. Somehow, I can’t see my workplace making a similar decision. It’d be awesome if we did, though.

I don’t yet know what will make linked data happen for the rest of us. I feel like we’ve spent years convincing traditionally-minded librarians of the virtues of linked data with precious little to show for it. We’re having the same conversations over and over. Making the same pronouncements. The same slides. The same tweets. All for something that our users will hopefully never notice. Because if we do our jobs right and somehow pull off the biggest advancement in library description since the invention of MARC, our users will have no reason to notice—discovery of library resources will be intuitive at last.

Now that would be something worth talking about.