This post is part of an occasional series, “Digital Preservation For the Rest of Us”.

Background

Ever heard the saying ‘the internet is forever’? Well, I’ve got good news and bad news. The internet does retain a staggeringly huge amount of information, but it doesn’t always last.

In the last couple of days we’ve heard about the abrupt shutdown of news organisations DNAinfo and Gothamist, with the sites being summarily yanked off the internet. Within hours, people realised that if those sites were gone for good, journalists and other contributors would have no way of verifying their work history, and years of valuable local journalism could be lost.

It followed the ABC’s recent decision to remove a few years’ worth of At the Movies videos as part of a transition of older websites for programs that have ceased broadcasting. Researchers were horrified by the idea that the ABC could simply ‘erase history’ by removing content from the public internet. Many commented on the avalanche of link rot the ABC had created.

While the At the Movies website was archived by the NLA’s Pandora service, the videos themselves were not archived (presumably for space and technical reasons). The ABC have also publicly stated they intend to move older video content from past shows to a better online archive. Compare that with Gothamist, which has found itself at the mercy of the Internet Archive and cached Google search results. A fair amount of content had been saved to the Internet Archive, but there are likely still gaps. It also highlighted how many people weren’t keeping personal archives of their work.

Key lessons

The internet is not your archive. I can’t emphasise this enough. The public internet is not—and was never designed to be—a permanent archive. Websites can be put up or taken down at a moment’s notice. Just because something is online right now, doesn’t mean it will still be online tomorrow, or next week, or next year. We can’t expect corporations and private organisations to archive their published work in perpetuity and have it be the only copy. That’s what libraries and archives are for. (Libraries around the world undertake national web archiving programs, incuding the NLA and the Library of Congress, but they can’t collect everything, and most can only collect material published or produced in their country.)

You cannot rely on others to archive your work. You will need to do this yourself. The best way to capture content in perpetuity, whether it’s physical or virtual, is with a mix of public and private archiving. That is, with archival tools and collecting policies controlled by public entities, by private entities, and by you personally. If one fails, the other two should persist. If all three fail, you’ve probably got bigger things to worry about.

How to archive your online articles

Here’s a selection of free tools to help you capture and archive your digital content.

- Save to Evernote. Evernote is a free cloud-based notes app for every platform you’d care to name. It’s good for notetaking, but the killer feature is its Web Clipper extension, the ability to scrape web pages and save them straight to a note. I use this religiously to keep all my internet detritus in one place, but you can use this to save copies of your online work.

- Add to the Internet Archive. The Internet Archive, perhaps the most well-known digital archive, incorporates the Wayback Machine, a privately-run web archiving service hoovering up the web since 1996. You can add individual pages to the Archive in several ways, including by copying and pasting a URL into this page, or by using a clipping extension (available for Chrome, Safari and Firefox, with apps available for iOS and Android). The extension will also detect dead pages or 404s and offer to take you to an archived version of that page, which is an incredibly useful tool.

- Create a personal web archive with Webrecorder. Webrecorder is an amazing web archiving tool built by Rhizome. You can navigate to the pages you wish to save, creating a personalied set of archived pages. You can then download this set to your computer, view it with the accompanying Webrecorder desktop app, and—this is the best bit—the pages behave exactly as they did when you saved them! Video, animations, dynamic pages—they all work (this isn’t always the case with the Wayback Machine). Great for multimedia artists and people who wish to browse their archived work in its natural habitat.

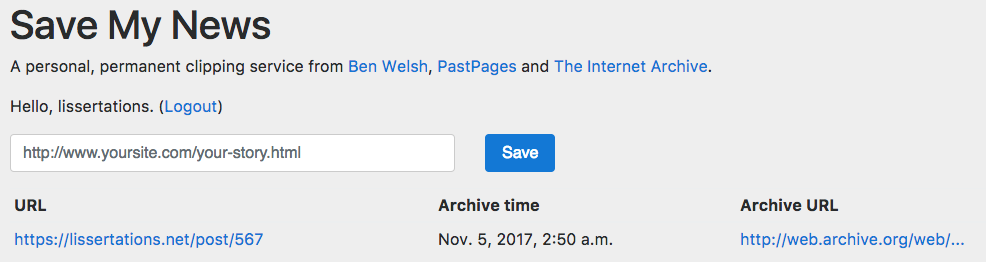

- Use Save My News. Save My News, a nifty little service brought to you by Ben Welsh, combines the cloud storage of the Internet Archive with the handy custom lists of Evernote or Webrecorder. Simply login with Twitter, copy and paste a URL, and bam! Instantly saved in the Wayback Machine, neatly arranged in a list for your reference. So simple, even your dog could do it.

- Print articles to PDF. In a browser, simply choose to print your page (Ctrl-P / Command-P). Select the printer “Save as PDF” and choose where to save the file, creating a neat PDF copy of your work. Be aware that some articles may not look quite the same if you choose to print, and interactive features won’t translate well to a static format.

- Print to actual paper, if you’re into that kind of thing. If you’re not entirely convinced by all thse new-fangled digital storage options, there’s always paper. Obviously your work will lose all those interactive features like scrolling and clicking, and the stylesheets might not come out right, but your paper copies may well outlast your hard drive.

Please feel free to share this post with anyone you think could use a personal archive of their own. Happy saving!