Is fheàrr Gàidhlig bhriste na Gàidhlig sa chiste.

It is better to have broken Gàidhlig than dead Gàidhlig.

— Scottish Gaelic proverb

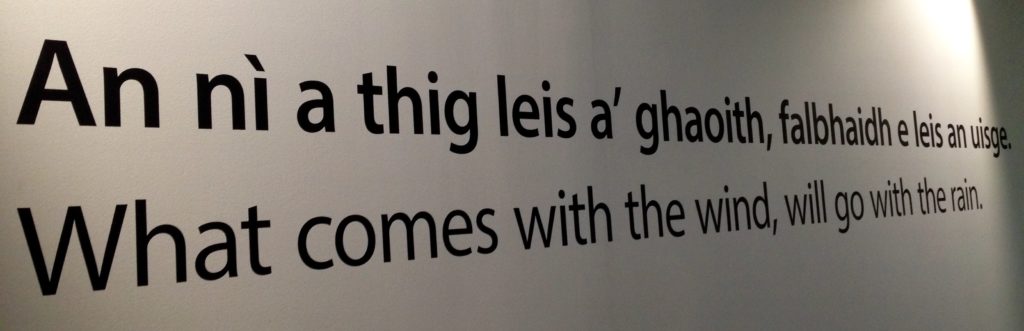

An invitation by GLAM Blog Club to discuss ‘identity’ has taken me in all sorts of unexpected directions. For one thing, I was fortunate enough to finally attend a Cardi Party, held this month at the Melbourne Immigration Museum, which has helped shape my nebulous thoughts. I’ve also spent most of this week in bed, fighting off a nasty illness gifted me by the city of Melbourne. You know I’ll be back, though.

Talking about identity invariably entails talking about yourself. Who you are, where you have come from, where you are going, what you believe, and so on. Yet it should also entail talking about everyone else, because identities are shared just as much as they are kept to oneself. Whatever I am, someone else is also.

The extent to which we might choose our identities has occupied my thoughts for some time. Identities can be (and are) granted, revoked, adopted, rejected, gifted, stolen, bought and sold. We express our identities in myriad ways—culture, language, ethnicity, dress, official papers, unofficial papers, oral histories, written histories, birth ceremonies, burial rites. Some of these identities have been chosen for me. Some I cannot change. Many I have picked for myself. A few have been thrust upon me. A couple taken by force.

About a year or so ago I began casually learning Gaelic. Known to speakers as Gàidhlig, a language understood by 1.7% of the people of Scotland,1 threatened with extinction in the long term, and spoken by less than a thousand people in Australia,2 it may appear a strange choice of hobby. For various reasons I haven’t been learning as intensely as I once did, but I enjoy following Twitter accounts in the language (using my other account @lis_gaidhlig) and am pleasantly surprised by how much I understand. Gaelic is closely related to Irish (Gaeilge) and Manx (Gaelg) and is part of the Celtic family of languages. It is not to be confused with Scots, the Germanic language closely related to English.

You’d be forgiven for wondering why I chose Gaelic. While it wasn’t originally my idea, it became something in which I was intermittently interested. I no longer have access to the learners’ guides, yet I’ve found myself actually using my skills more than ever. Curiously, I don’t know if any of my ancestors ever actually spoke Gaelic (I think it’s likely, but I’d have to ask my grandmother); certainly nobody in my extended family currently speaks the language.

Writing this post represented the first time I started to think critically about my relationship with Gaelic. I began asking myself copious questions, most of which I couldn’t immediately answer. Did I choose Gaelic (or was Gaelic chosen for me) out of a genuine desire to reconnect with my Scottish roots? My (extremely) Scottish surname was handed down through my family’s 150-odd years of Australian habitation, and yet it was not the name I was born with. I chose this name, much as I chose my family. Does the name conceal other areas of Britain and Europe from which I am descended? Why did I choose this strand of ancestry and not others?

Is there a performative aspect to this exploration of my identity? Am I only aligning myself more with ‘Scottish’ because it’s politically expedient to not be ‘English’? Is it part of a quest for a more concrete ethnicity than ‘generic white Australian’? Am I echoing middle-class Lowland Scots in appropriating a culture and language which is no longer truly mine? Gaelic-speaking regions of Scotland (today, chiefly the Hebrides) are cold, remote and economically disadvantaged. Is it my place to enjoy the good things without the bad?

Am I looking for a point of difference? A homeland? A place I can point to, despite never having lived there, and say ‘That is my home’? I was privileged to visit Scotland last year, the realisation of a lifelong dream. When I first saw the outskirts of Edinburgh from the plane window, Scotland felt like the strange, exciting, foreign country it was. But it also felt like home. Should it have done?

Is it a response to becoming more educated and aware (some might say ‘woke’) about the black history of Australia, and in particular what Scottish settlers did to Aboriginal people? A reaction to the knowledge that the land I live on, the only home I have ever known, is not mine and was never ceded? A realisation that if I were to repatriate myself, to go back to where I came from, I’d better know where to start?

Moreover, had this sudden interest rendered me the Scottish equivalent of a ‘weeaboo’, because I drink whisky and Irn Bru, listen to a lot of Gaelic folk music and have strong views on Scottish independence? I decided it had not, chiefly because I don’t think everything from or about Scotland is automatically superior to non-Scottish equivalents. (Surprisingly, the thing I missed most about Australia when I visited Scotland was a supply of fresh fruit and vegetables!)

When asked, I don’t tell people that I’m Scottish, because I’m not. I’ve never lived in Scotland, I’ve visited only once, I don’t hold a passport and I don’t speak the language. I say I’m Australian and leave it at that. Occasionally I might get ‘where’s your family from’ (not the more insulting ‘where are you really from’ doled out to non-white people), at which point I might specify Scotland. Yet where is the line drawn between ‘having Scottish heritage’ (or any other ethnocultural affiliation) and ‘being Scottish’? At what point, if any, will I ever be ‘Scottish enough’?

Seeing the Highland tartan exhibit at the Immigration Museum brought a lot of these issues into sharp focus. The Clan MacDonald tartan, easily recognisable with its bold reds and muted greens, formed the backdrop to a medal made of silver, a first prize for dance at the Buninyong Highland Society in country Victoria. Inscribed on the obverse is a curious epigraph, left untranslated by curators: ‘Làmh na Ceartais’. The hand of justice. But for whom?

While researching the background to this post I discovered two books that might help me answer some of my questions surrounding the legitimacy of my Scottish identity. The first is The Survey of Scottish Gaelic in Australia and New Zealand, a 2004 PhD thesis by St John Skilton. It documents the efforts of Scottish expats, descendants of immigrants and interested learners to keep the language alive an leth-chruinne a deas (in the Southern Hemisphere), as well as broader questions of Gaelic ethnicity in Australia and LOTE teaching traditions in Australian schools. At almost 400 pages it’s a hefty read, but one I intend to savour.

The second is Caledonia Australis, a 1984 book by Don Watson exploring the intersection of emigrant Scottish Highlanders and the indigenous Kurnai people of what is now Gippsland in eastern Victoria. Many Highland Scots were forced to emigrate after being thrown off their land by the English during the Highland Clearances. Those who sailed to Australia systematically dispossessed Aboriginal people of their land, just as the English had dispossessed the Highlanders of theirs. I haven’t yet gotten my hands on a copy of this book, and I regret that I could not incorporate its histories into this post.

For a final word on Gaelic identity, I turn to Sorley MacLean (Somhairle MacGill-Eain, 1911-1996), one of the great Gaelic writers and poets. His thoughts on the topic (in English) were set to music in ‘Somhairle’ by the Gaelic electronic band Niteworks, whose album NW is one of my favourites. (I recently bought their gear on Bandcamp and conversed with one of the band members in Gaelic!) Sorley was an ardent defender of his culture and language in the face of English dominance and destruction. It seems only fitting that his words lend us a sense of his grim determination to survive, as well as that of his language.

Ever since I was a boy in Raasay

and became aware of the differences between the history I read in books

and the oral accounts I heard around me,

I have been very sceptical of what might be called received history;

the million people for instance who died in Ireland in the nineteenth century;

the million more who had to emigrate;

the thousands of families forced from their homes in the Highlands and Islands.

Why was all that?

Famine? Overpopulation? Improvement? The Industrial Revolution? Expansion overseas?

You see not many of these people understood such words,

they knew only Gaelic.

But we know now another set of words:

clearance, empire, profit, exploitation,

and today we live with the bitter legacy of that kind of history.

Our Gaelic language is threatened with extinction,

our way of life besieged by the forces of international big business,

our countries beggared by bad communication,

our culture is depreciated by the sentimentality of those who have gone away.

We have, I think, a deep sense of generation and community

but that has in so many ways been broken.

We have a history of resistance but now

mainly in the songs we sing.

Our children are bred for emigration.

- Scotland’s Census 2011: Gaelic report (part 1) (this encompasses all levels of fluency, so the number of true speakers is certainly lower) ↩

- The Survey of Scottish Gaelic in Australia and New Zealand, 2004, p. 183 (it’s closer to 800, and that was in 2003) ↩