A few days ago I had the pleasure and privilege of attending the inaugural VALA Tech Camp, a two-day symposium for librarians in tech and technologists in libraries. I learnt a lot and had an excellent time, thanks in large part to the Herculean efforts of the organising committee. Below are a few scattered and not entirely comprehensive thoughts on the event:

Coding is easy! Coding is hard! When the committee asked for suggestions on what to include in the camp, I asked for fairly basic stuff—an intro to Python, for example, for those of us at the n00b end of the spectrum. A 2-hour crash course in Python wound up being the first event on day 1, so I felt more or less obliged to attend. I had previously tried several times to teach myself Python (out of books, on Codecademy, from YouTube videos) but had realised I needed an actual person to teach me the basics.

By the end of the session I had achieved the following:

Omg! I wrote a line of code! And it broke! And I know *why* it broke! And I fixed it! Feeling super empowered rn #VALATechCamp

— Alissa M. (@lissertations) July 13, 2017

I was not expecting 56 people to be so supportive of my own personal Wow! signal, so that was super nice. The workshop really did feel like the booster I needed to get me started in Python.

Later in the day (and continuing on day 2) was ‘Hacky Hour’, essentially free time to work on coding projects. I started out doing some web scraping with ParseHub and Beautiful Soup, then got bored and wound up with a Trove API key trying to rewrite Libraries Australia SOLR queries as Trove API queries (with mixed results), then got bored again and started writing a Bash script to extract metadata from a PDF into a CSV or TXT file.

The latter occupied my time and imagination even after I returned to the hotel, culminating in me figuring out how to export metadata from a PDF to a CSV, then to OpenRefine, then to MARC! I was thrilled to have actually achieved something concrete that I could take back to work and actually use. If that was all I got out of VALA tech camp, it would have been worth it.

There’s a huge gap between what tech can do and what people think tech can do. Ingrid Mason spoke at length about the gap in not just digital literacy, but digital infrastructure literacy. You might know how to use wifi, but would you know how to fix your wifi if it broke? (I know I wouldn’t, and I’m more tech literate than the average person.)

There’s also the problem of extremely clever people constantly creating new ways to do things and new ways to solve problems, including library problems, but how much of that knowledge trickles down to us at the coalface? It’s something I’m keen to explore and maybe, hopefully, change.

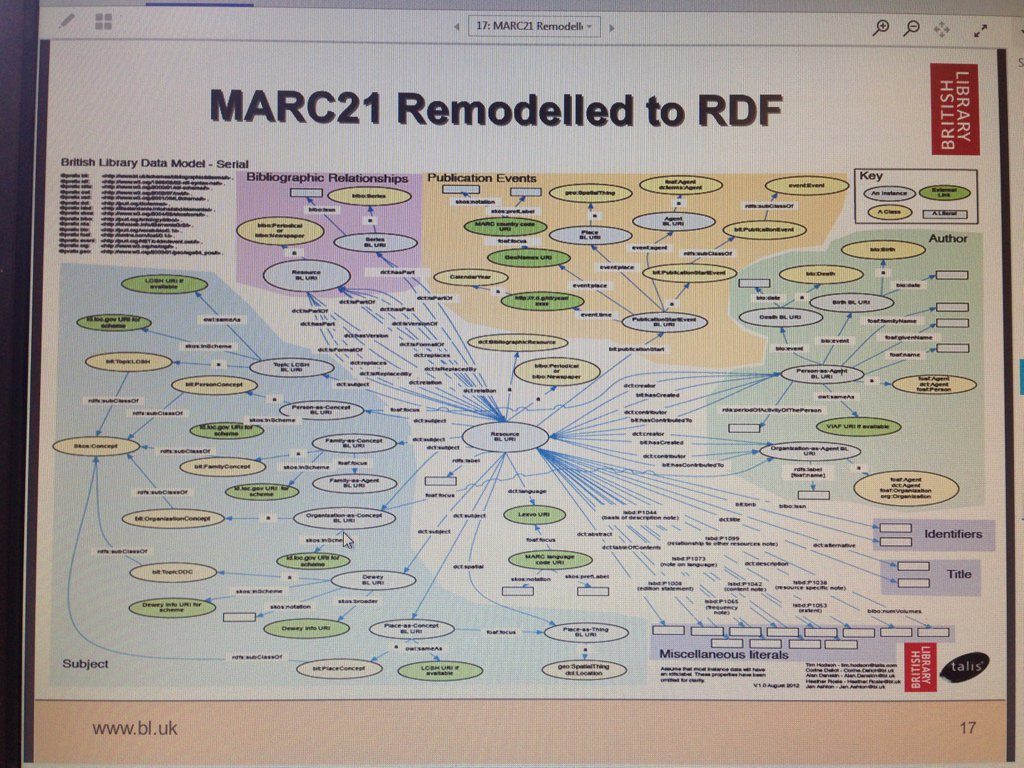

I was surprised by how much I already knew. One of my problems in tech is that I know I have a very uneven skillset. I am a total Python n00b, yet I can cobble together a Bash script. I’m totally across LOD and RDF triples, but didn’t know how SPARQL worked (until I attended the SPARQL talk!) I understood the mechanics of web scraping, but not how to properly harness web scraping tools. Even the talks where I came armed with a little background knowledge (like UX, APIs, the importance of good documentation) I left feeling twice as knowledgeable, which is an excellent outcome.

I particularly enjoyed the SPARQL talk because it explained linked data concepts in a way ordinary people could understand. Their use of Wikidata as an example SPARQL interface was an inspired choice—I felt it helped make an otherwise arcane and distant concept really concrete and accessible to a lay user.

Tech people are less intimidating than I thought. The attendee profile of VALA Tech Camp certainly skewed older, maler and more experienced than NLS8, which at first was a bit scary for this young, female n00b, but this is precisely why I went in the first place: to learn, and to find out what others are doing. I struck up some great convos with attendees of all genders doing excellent things. I wound up on an all-ladies table for the first Hacky Hour, the ‘Number 1 Ladies Solving Each Other’s Data Collection Problems’ table (moniker by me). In each situation people were only too happy to help and to chat.

Interestingly, I realised that in order for me to do better in tech, I would probably feel more comfortable in a women-only environment, like PyLadies or RubyGirls or something. I’ll look into local chapters and see if I could contribute. Seeing other women do super well in library tech was really empowering and wonderful, and I’d love to see more of it.

You can do the thing! ? Several short talks focussed on getting out there and just making stuff happen, including Justine on podcasting in libraries and Athina on running a cryptoparty in a public library. It was really inspiring to hear of people taking initiative and making excellent things happen.

On a much smaller scale, I found myself much more able to get out there and do things I find really difficult. Yes, I can go and make small talk to people! Yes, I can summon the courage to thank people for writing things that have meant a lot to me! Yes, I can do the thing! Yes I can.

Yes I can.