Last week at work I had one of the most incredibly serendipitous experiences of my library career. It was a beautiful illustration of why I became a librarian. To not only collect and preserve people’s stories, but to sometimes be part of them, and weave a broader tale.

It began in early January, when 110 books turned up from the same publisher. Being in the legal deposit business, my job is to catalogue whatever turns up in the post. Any genre, subject, author, publisher, size, format, you name it, I deal with it. (Unless it’s a serial.) We often get large boxes of books from publishers, but this particular enormous haul intrigued me. I volunteered to catalogue the lot. What can I say, I’m a sucker for punishment. And I wanted something fun to do before I went on holidays.

I slowly realised I held an entire library in my processing trolley. A living, breathing library.

It all started a few years ago in Iceland, where apparently one in ten people publish a book in their lifetime. Margaret Woodward and Justy Phillips, co-founders of Tasmanian arts collective A Published Event, found themselves in Iceland in 2012 doing arty things. They wondered whether there was a similar latent writing community in Tasmania, which is around the same size. Most of us would probably have pondered this for a short while and left it at that. But not these two. They decided to create a kind of performance library, soliciting unpublished manuscripts from would-be Tasmanian authors and publishing a whole lot of them in one go. Giving a voice to people who might otherwise never have published a book. Creating a kind of ‘time capsule’ showcasing Tasmanian life and writing during the late twenty-teens. It’s huge. It’s faintly ridiculous. And it’s completely awesome.

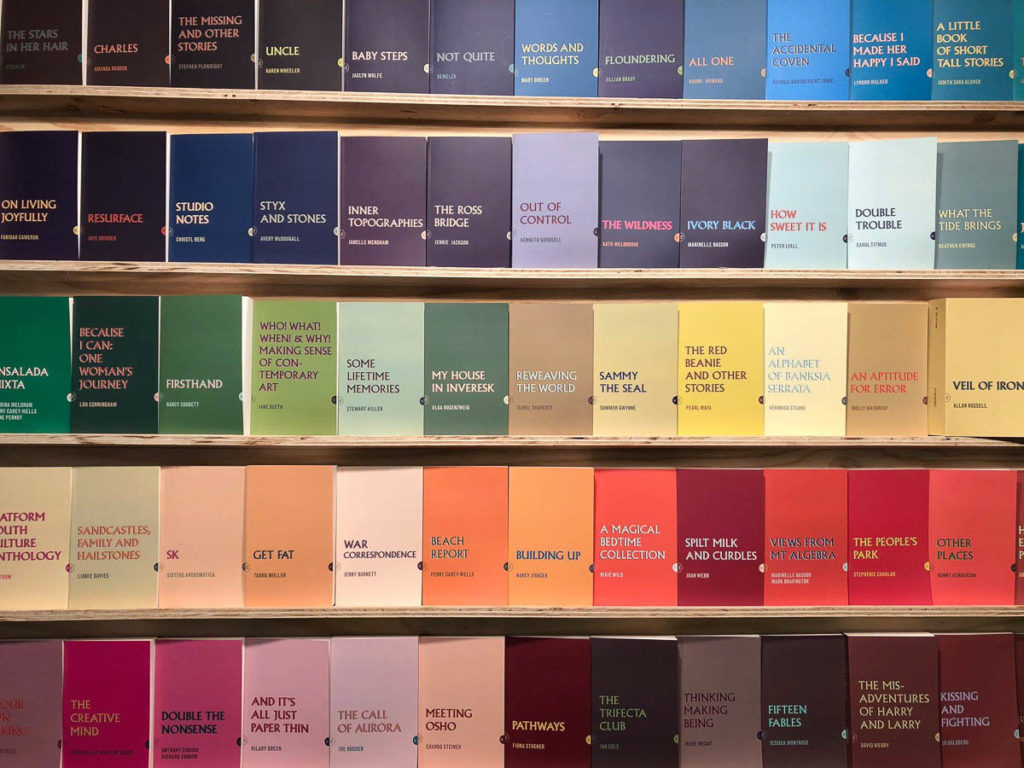

The People’s Library comprises 113 books. Their authors range in age from 15 to 94. All live in Tasmania, from all kinds of backgrounds, writing all sorts of things. Novels by first-time authors. Anthologies by U3A writers’ groups. Memoirs. Poetry. Non-fiction. Experimental literature. An opera about Sir Douglas Mawson, no less. Each assigned a cover colour from Werner’s nomenclature of colours, creating a beautiful rainbow effect when the books are lined up in order on a shelf.

The People’s Library was installed at Salamanca Arts Centre, Hobart, in September 2018. Authors read, performed and gave life to their stories. There were panels, responsive art pieces, readers-in-residence (and also readers-in-bed). The books took centre stage. None were for sale—this was a library, after all.

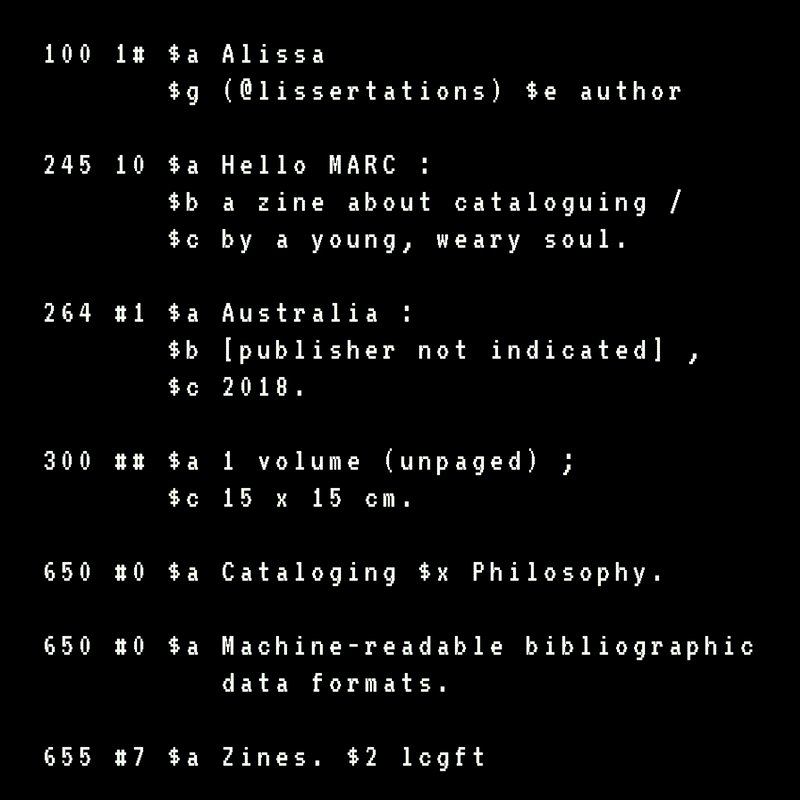

Then it came to us. To me. Cataloguing these wonders took me a full, magnificent week. They were a joy to process. I learned so much about Tasmania, about total strangers, about the limits of the written word, and even about myself. I realised we were missing three of the books, so an email was sent politely requesting copies. I returned after a month’s holiday (in Tasmania, as it happened) to an email from the publishers, promising to send the missing books and wanting to know more about how the Library was catalogued. Omg. A genuine interest in cataloging. Nobody ever asks me how I’ve catalogued their books unless they’re complaining about it, so I was very excited. I promptly wrote back with probably too much detail, which amusingly made its way back to some of the authors. Many of them were thrilled that we had collected and preserved their books.

And then I thought no more of it until last Wednesday, when I sat at the reference desk for my weekly shift. Not all cataloguers do shifts in the reading rooms, but some of us do. It was one of the first things I asked to do when I started this job, because I want to keep in touch with how people actually use and experience the library, and how the metadata I create might be a help or a hindrance.

I noticed a few volumes of The People’s Library on the collection shelves, ready for a reader to peruse. Occasionally people actually read the books I catalogue, which is always nice. I hastily arranged the volumes in colour order. The reader arrived and I retrieved the books. As I carried over the last handful I remarked, ‘I catalogued these books, they’re awesome.’ The reader looked at me oddly. ‘Are you… oh, you’re the one who sent us that lovely email!’

One half of A Published Event. In town for other reasons, but who had popped in to admire her handiwork. I had no idea she was coming, let alone during the two hours a week I spend on the desk. To have come all that way, to read some of the books she had given life to, and to have been greeted by the very same person who had lovingly catalogued them, and who only briefly sits at the reference desk… Absolute serendipity. You couldn’t have written it.

The fact it had taken me a week to catalogue the Library was cause for amusement. As part of the Library’s performance at Salamanca Arts Centre, four readers-in-residence had each read some of the books, also for a week, and produced a digest summarising what they had read and learned. In a way, she supposed I became the fifth reader-in-residence, and the catalogue records for these books constituted a fifth digest. An incredible way that librarians not only collect and preserve stories, but can sometimes be part of them. By cataloguing The People’s Library I became a part of its performance, weaving a broader tale, ensuring the voices of over a hundred Tasmanians can be read and heard by all who visit us. I felt honoured to be a part of this work.

I already can’t wait to peruse A Published Event’s next library, Lost Rocks, a collection of 40 ‘fictionellas’ borne from an almost-empty rock board picked up at the tip shop in Glenorchy. ‘A slow-publishing event of mineralogical, metaphysical and metallurgical telling.’ It doesn’t get better than this.