I did a lot of watching this month. It never sits well with me, watching. It’s too passive. I want to jump up and do things. Make things. Break things. Change things.

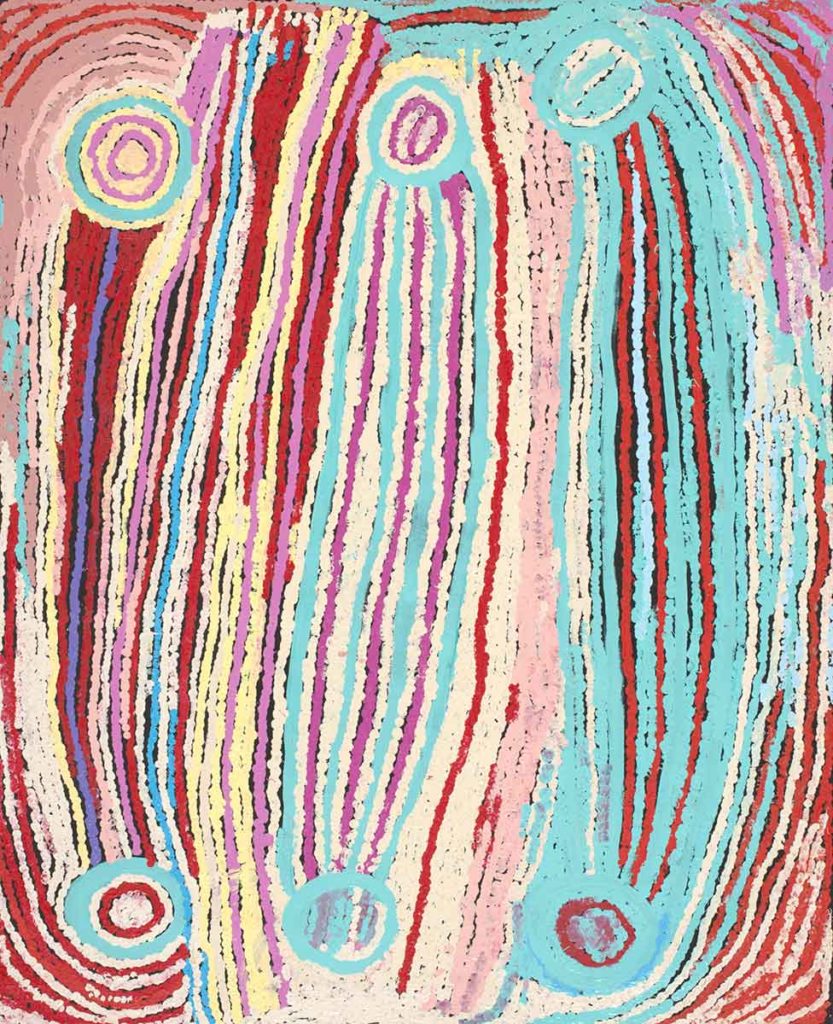

This month, I was excited to attend my second ever CardiParty: the exhibition Unfinished Business at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. I grew up in a household that couldn’t have cared less about art, and here I was, visiting art galleries on my weekend off. Feminist art galleries. On my birthday, no less!

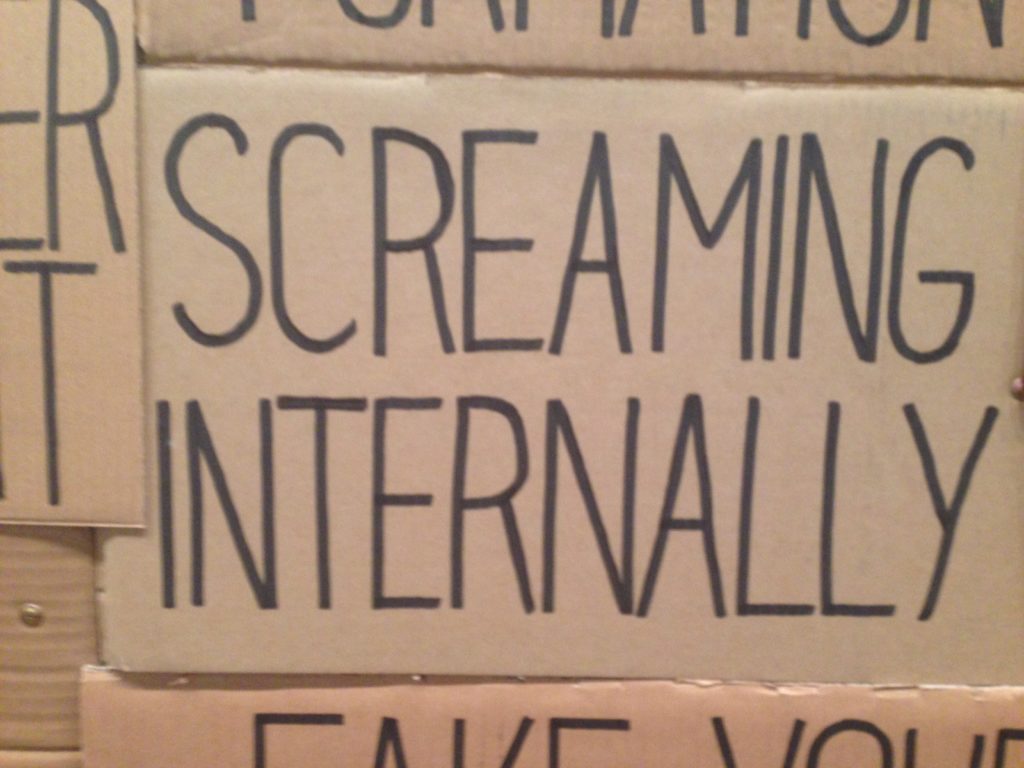

The gallery was chock-a-block with eye-catching, provocative art, but my favourite piece was I am with you, a 7 square-metre collage of fake protest posters featuring real slogans. I wanted them on a t-shirt. I think I said to Kassi I wanted to decorate my house with everything in the room (though on reflection I think I might pass on the metal sculpture of the inside of someone’s vagina).

Despite having the artistic capability of a garden snail I was filled with a strange compulsion to do art. Watching art created by other people suddenly wasn’t enough. I didn’t know what I might do—I had no experience of doing it. I had this incredible need to express myself, artistically. To create, somehow. To be more than words.

Perhaps my brain processed that as ‘Well, you’re no good at art, but what are you good at? PANICKING’ and I promptly had a sub-acute panic episode at the cardiparty afterlunch, followed later that night by a second episode so acute I called triple-zero and asked them to come round and make sure I wasn’t dying, please. It was horrendous. I think I’d prefer art.

The next day I visited the NGV Triennial, because everyone on twitter told me to. I was pleasantly surprised by the interactivity of the art. Pieces so close you were encouraged to touch them, art that took up entire rooms, things you could lie down on and soak up. Art you could feel. One installation was set up like an ordinary loungeroom, with a real person watching a video of their choice. I’ve no idea what was playing when I visited, but it looked like some kind of hair metal concert.

I stepped around a few corners and into a dark hallway. Beyond, I caught a glimpse of Moving creates vortices and vortices create movement, an enthralling installation by Japanese art collective teamLab. Sensors track the movement of your feet and project little dancing lights around them, a contrast against the whirls of blue projected on the floor. It was incredible. It felt like seeing Dust for the first time.

The room filled me with a profound sense of worth, of purpose, of wholeness, of consciousness. It was healing, it was overpowering and it was very real. I didn’t want to leave. I wanted to watch the lights forever, wanted the vortex to swallow me whole. A picture doesn’t do it justice. Experience the room, if you can. But be careful, there’s a warning just outside not to stay in too long, because it can make you dizzy.

I think I would like to include more art in my life. But I don’t want to watch art. I want to do art, even if it’s terrible. I want to squeeze art through my fingers and throw art all over the house and fling myself in a pool filled with art.

Do art. Make art. Break art. Change art.

And maybe scream a little less, internally.