I have a lot to get done this year. I’d like to graduate at some point, I’m drowning in work (as usual) and my house is a tip, but there are plenty of broader goals to set. I’m pleased that #GLAMblogclub is now a thing and look forward to the benefits it will bring to the local GLAM blogging industry.

The below is essentially a public to-do list for myself. I hope to be productive enough to actually tick these off in December, which would be most satisfying.

Improve my digital skills

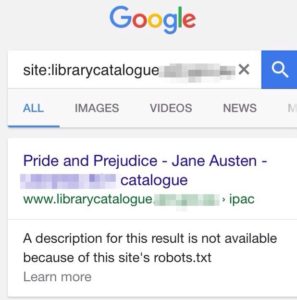

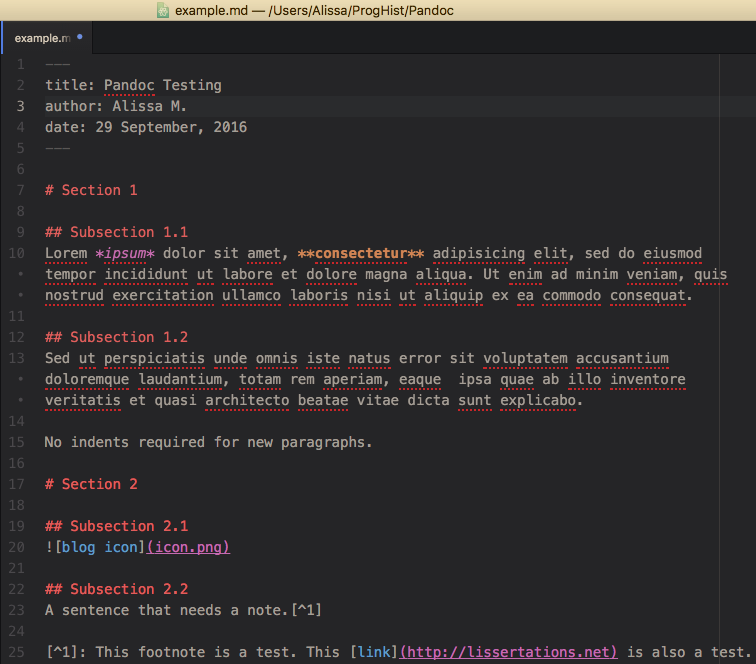

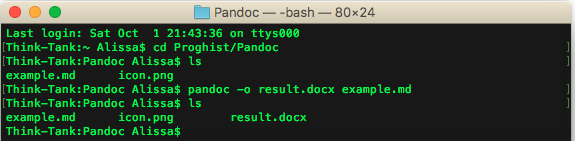

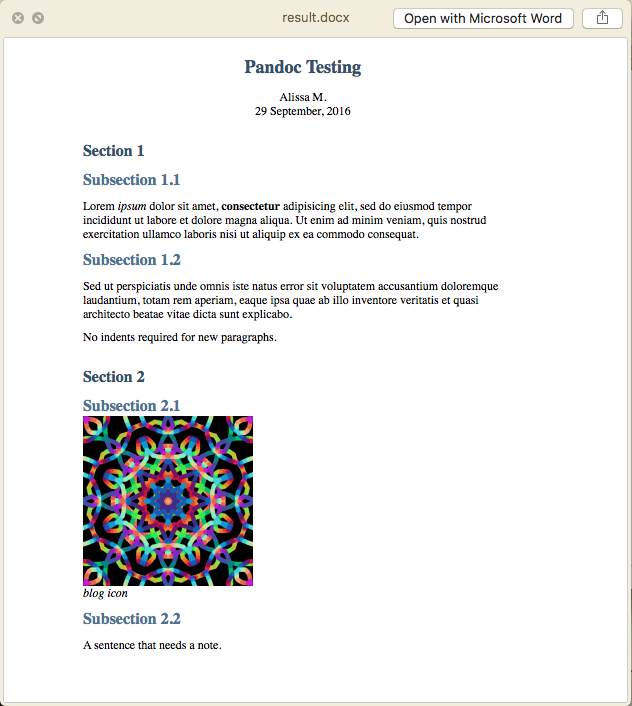

For all my fascination with digital preservation, digital archiving and digital librarianship, my skills in this area are sadly deficient. There’s a lot I don’t know and a lot I’m having to teach myself. Learning on the job is fun, but I know I need to up my game.

I’ve resolved to learn SQL this year, largely because it would be directly relevant to my job—there’s a lot of metadata work in my future and being able to craft my own queries would be very useful. A friend has expressed interest in taking a Python class, so we’ll see if that leads somewhere. I know I’ll have to bite the bullet and get a new computer this year, so perhaps I’ll be brave enough to take the plunge and install Ubuntu.

I’m also hoping to improve my command line skills to be able to do more fun web archiving things, as well as take advantage of the incredible tools at Documenting the Now and the Programming Historian.

Reconnect with long-form writing, which is worth paying for

I have a terrible habit the Japanese call 積ん読 [tsundoku], acquiring books and then not reading them. I am surrounded by books I bought, snaffled, borrowed from the library and was given as gifts. Strictly speaking I have plenty of time to read them, but I usually end up doing things that require a shorter attention span.

This year, it’s time to put my money where my mouth is. As I write this, my desk holds no fewer than eleven thirteen unread books (plus two unwatched DVDs and one unheard album). I’m going to try reading at least two books a month, one at a time. Right now I’ve just begun reading Sisters of the revolution: a feminist speculative fiction anthology, which is comprised of bite-size chunks I can happily digest. I generally don’t read fiction very often, but I’m enjoying this book.

In addition, I intend to get my journal subscriptions in order. Open-access publishing is truly revolutionary and I am grateful for such excellent OA LIS journals as Weave, code4lib, Practical Technology for Archives and the Journal of New Librarianship (neatly syndicated by, among other handles, @OALISjrnls). However, I am firmly of the belief that good writing is worth paying for, and that people should not feel obliged to contribute their labour for free. To that end, I’d like to subscribe to a couple of long-form print journals this year. I’m not sure what yet. Something considered, something literary, something thoughtful. Suggestions, as always, are welcome.

Get some perspective

One of the hallmarks of our era is the modern human’s inability, generally speaking, to see things from another’s point of view. Social media (especially Facebook) excels at crafting a world where the news is just as you’d like it, full of stories it hopes you find agreeable. No longer are we assured that our family, friends and colleagues are all reading the same news (if they read the news at all); nor can we be sure that what they do read has any truth to it. The truth of a story appears, for all intents and purposes, to be less important than the emotions it might cause. My profession is reeling from the apparent common disregard for verifiable information and considered thought.

Like most people, I’m quite accomplished at avoiding news I don’t want to hear. On one hand, I consider it a duty of my profession to be well-informed about the world; on the other, moving to a remote Scottish island is looking more and more attractive (and it’s not just for the climate). This makes for a comfortable existence. It’s gotta stop.

I lead a privileged life: doing a job I love, in a country led by someone who is not a far-right nationalist, with all the food, shelter and self-actualisation I could want. Most humans are not nearly as fortunate as I am. Consequently, I have a particular set of views about most issues. I’m learning the hard way that a lot of people see the world very differently from how I see it. I cannot hope to influence that which I do not understand—so I’d better start trying to see things from the other side. (I don’t yet have a metric by which I might measure my progress, but I’ll think of one.)

It’s time to get some perspective. It’s time to learn dangerously.