Today I went to see the exhibition Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters at the National Museum of Australia. I was motivated to spend today somewhere airconditioned, and figured I could tick off this exhibition on my to-do list at the same time. As it turned out, I’m already planning a second visit.

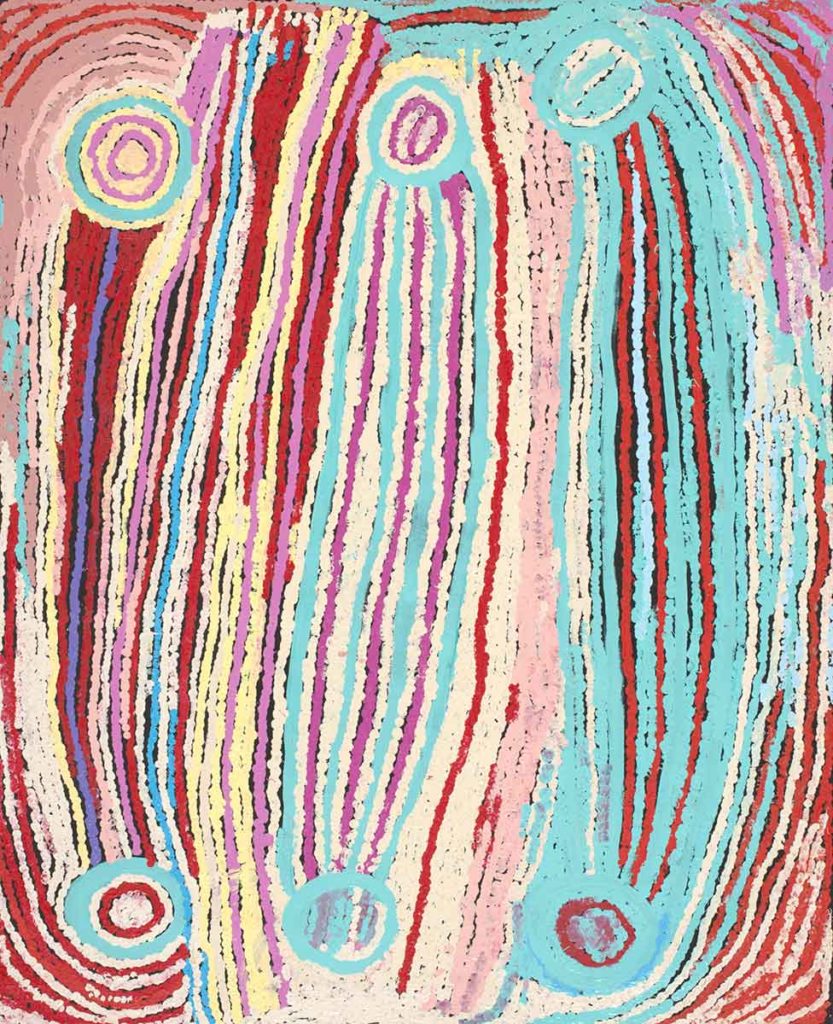

Songlines is an incredible, spellbinding exhibition. I implore you, if you can, to see it before it closes on February 25. It’s an enthralling journey across space, time, culture, language and people, telling an Indigenous story in Indigenous ways—paintings, ceramics, carvings, song, dance, oral retelling, even a virtual reality experience depicting Cave Hill rock art. The saga of the Seven Sisters (Minyipuru in Martu country, Kungkarrangkalpa in Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara [APY] country) incorporates essential knowledge for survival in the desert—the locations of waterholes, medicinal plants and food sources, sacred places, areas of risk, how to mitigate that risk.

I came to the exhibition with some awareness of Indigenous desert culture and left with an exponentially greater understanding of Martu and APY lore, culture and knowledge. I felt an incredible sorrow at what settler culture had inflicted on these people. An incredible awe at their continuing survival. An incredible gratitude that they had chosen to share this lore with Australia, and that I might experience it. An incredible sadness that their ways of life were imperiled to the point that APY elders considered it necessary to stage this exhibition at all.

Songlines also made clear that this story was being shared with me, with the public, with settler Australia, because the elders wanted it shared. That non-owners of the tjukurrpa (the Dreaming) were not necessarily entitled to this knowledge, and would not traditionally be privy to it. The concept of ‘entitlement to knowledge’ was fortunately not new to me, but I found myself returning to it during my almost three-hour stay in the exhibition space. It had represented a profound shift in my conceptualisation of self, both my personal white self and my professional librarian self.

Modern western librarianship has its roots in the Enlightenment ethos of the primacy of reason: rationalism, scepticism, empiricism, objectivism. All of those -isms naturally presuppose access to knowledge, which builds logical argument and constructs a rational worldview. The idea that an Enlightenment thinker might be, in their view, denied access to knowledge that might advance their philosophy… it would be inconceivable. It goes far deeper than ‘I don’t want to tell you because I’m a competing philosopher’. It’s an intrinsic entitlement to knowledge. A staunchly-held view that worldly knowledge is there, just there, for the taking.

This line of thinking has trickled down to us today. I spent my childhood voraciously consuming every book, newspaper, magazine and educational computer game I could get my hands on. I brought to librarianship the same thirst for knowledge that defined my early years. I saw nothing wrong with this. It wasn’t until very recently—say, the last 18 months or so—that I began learning far more about Indigenous epistemologies and methods of knowledge transmission, and in doing so beginning to question the very foundations of my profession.

What sorts of knowledge am I entitled to? If any? What knowledge should I be sharing, not sharing, promulgating, not promulgating, making findable, making secret? The idea that not all knowledge ought to be public knowledge, that not everything ought to be shared, is a seismic shift in western librarianship. Consider our current preoccupation with linked open data. Not all data is appropriately shared in these kinds of frameworks, which is why Indigenous data sovereignty is essential for any open data project. Knowledge is not always ours for the taking. Knowledge belongs to people, and their interests must always come first.

I picked up a book in the museum gift shop, Glenn Morrison’s Songlines and fault lines: epic walks of the Red Centre. I’ve accidentally read half of it already, though I had hoped to do it justice and soak up the book in one sitting. It’s a wonderful addition to my growing collection of books on psychogeography, a burgeoning interest of mine, which is basically a white way of trying to establish a (spiritual?) connection with places and with the landscape. I left the exhibition painfully aware of the connection I do not have with this land, partly because I’ve only recently tried to reconnect with walking and nature, and also because it’s not my land.

In any case, I look forward to returning to the Songlines exhibition. There’s so much more I could learn from it, for as long as it deigns to teach me.