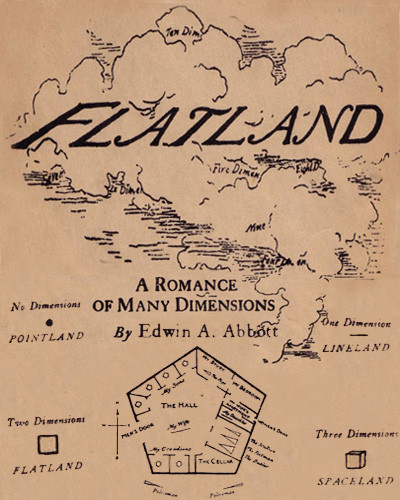

The other day I decided I’d better get started on the books in my enormous to-read pile, preferably before I have to return half of them to the library I work at. The topmost book just happened to be Flatland: a romance of many dimensions (1884) by Edwin Abbott Abbott (1838-1926). A colleague had recommended it to me as part of a potential display on ‘flat’ books. (We share a building with a public library branch, and I was thinking of doing a book display which, for once, had nothing to do with local history. I seem to recall being in a flat mood at the time.)

I hadn’t even opened the cover when I was distracted by the book’s call number. This happens to me a lot.

530. 11 ABBO

Flatland, as far as I can ascertain, is a work of fiction, and has been since 1884. Why was it classed in non-fiction? Is this a common view? Who made this decision, and why did they make it?

Firstly, let’s examine this number. DDC 530.11 is the home of general relativity, among such physics luminaries as Albert Einstein, Stephen Hawking, Lawrence Knauss and Brian Cox (whose works on the subject are definitely not fiction). Einstein popularised (and drew on others’ efforts in consolidating) the theory of general relativity in 1915.1 That is, over thirty years after Flatland was published. How can this be?

Is it because Flatland is primarily about science, and the term ‘science fiction’ didn’t exist when the book was published? Did the cataloguer of this particular item even know it was a work of fiction? I flipped the book over and read the synopsis. “Flatland (1884) is an influentual mathematical fantasy […] A classic of early science fiction.” Hmm. Looks fairly clearcut to me. Maybe they weren’t in a synopsis-reading mood.

I then looked at the book’s CiP details. Which call numbers did they provide?

PR4000 823. .A22 8 F53 2009

‘Aha!’ I exclaimed, to nobody in particular. So even the CiP cataloguer knew it was fiction, and classified it as such! The LCC call number PR4000 is English literature > 19th century, 1770/1800-1890/1900 > Individual authors (with A22 F53 presumably being the cutter for Abbott, Edwin. Flatland), while DDC 823.8 is Victorian-era English literature. I’m beginning to get a bit cross at our cataloguer by this point, who seemingly hasn’t read either the synopsis or the CiP data.

I’ve now spent over an hour investigating this book. I haven’t even started reading it yet.

Interestingly, the CiP for this work was done by Library and Archives Canada, as the editor of this particular version is Canadian. Hmm. Did Library of Congress treat this book differently? (No offence, Canada)

I had a peek at the Libraries Australia record for this edition. This record is an LC copycat job, using the original Canadian data, but making a few slight changes…

QA699 530. .A13 11 2010b

Bingo!! So that’s why the cataloguer of my copy of Flatland thought it was non-fiction—because Library of Congress did too! … Or did they?

While DDC 520.11 is for relativity, as discussed above, LCC QA699 includes a fascinating—and critical—scope note: Geometry > Hyperspace > Popular works. Fiction (Including Flatland, fourth dimension)

According to LC, it is so crucial that Flatland be classed with non-fiction works on hyperspace that it’s literally namechecked in the scope note! This is amazing! But why did they do that? And why was this logic reproduced in DDC?

I then decided to browse LC’s collections at QA699 to see what else was there. The most recent work appeared to date from 1971, with the bulk of works (excluding revised and edited editions, of which the book in my hand is one) dating from the late 19th and early 20th century.

A quick scan of works in QA699 suggested almost all of them were indexed with the LCSH $a Fourth dimension. The scope note for this heading reads: Here are entered philosophical and imaginative works.

Mathematical works are entered under Hyperspace.

LC holds 100 items with this heading, but it also holds 5 items indexed $a Fourth dimension $v Fiction, which are not classed in QA699. These items include a book about Flatland: the movie edition (2008) and four novels published in the 21st century.

So what is this telling me? Flatland, according to LC, is a ‘philosophical’ or ‘imaginative work’, which suggests they think it’s too intellectual to be considered merely a work of fiction. But this seems like a load of crap to me. Isn’t all fiction inherently ‘imaginative work’? Is Flatland accorded this kind of respect because it’s old, was written by a white man, and has increased in intellectual stature over time? Did the cataloguer at LC who originally wrote the QA699 scope note (however many years ago that was, and may or may not have been the same cataloguer who processed Flatland) decide that this work was not mere literature, fit for the P class, but a higher-order piece of writing that ought to reside near the subjects it fictionalised?

Hmph. This reeks of classism to me.

But it also explains why the book in my hand has the entirely inappropriate DDC call number 530.11: the cataloguer at LC probably looked up the closest thing to ‘Hyperspace’ in DDC (that being ‘Relativity’), either didn’t notice or didn’t care about the ‘Fiction’ aspect of QA699, classed the book where DDC said to and moved on with their life, with dozens of subsequent copy cataloguers not knowing, not caring, or not being paid enough to reconsider this choice. I’ve stopped being cross at our cataloguer, who clearly saw no reason not to defy the ANBD record. I can understand where they were coming from.

For me, the question now becomes: will I change it locally? Technically I have this ability, but because it’s not a local history book I’m supposed to refer it to our collections team. They have way more important things to do than change the call number of a perfectly findable item, especially because nobody’s yet complained about it.

I’ll think about what to do next. For now, though, after several hours of investigation and writing, I might actually get started on the book.

I think it’s the least I could do.

- For a longer explanation of why I didn’t just say ‘invented’ like everyone else, see this piece on ‘Who invented relativity?’ http://www.mathpages.com/rr/s8-08/8-08.htm ↩